After covering Vemo for several years, I have learned to take company announcements with a grain of salt.

In 2018, for example, Wemo said it would launch a full driverless merchant service by the end of the year. Wimo introduced a service called Wimo One in December 2018, but it came with a lot of giant stars: each vehicle has a safety driver, and the service was only open to a small group of people.

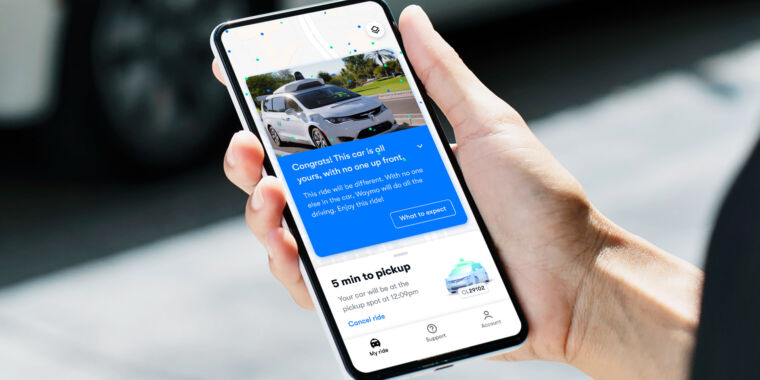

But today it looks like Wyoming will finally start the taxi service it promised two years ago: one it is completely driverless and open to the public. Wimo told Arsen that the service would initially operate in a 50-square-mile area in the Phoenix suburbs of Chandler, Tempe and Mesa.

The Wamo rollout of driverless technology has been so slow and confusing that it’s easy to lose sight of what a remarkable achievement this is. In the last one or two years, since driverless technology has failed to live up to the previous hype, it has become fashionable to claim driverless technology is still years or decades away.

But that is not true. Public members living in the Chandler area can enjoy a full driverless taxi today.

Now Wemo’s big challenge is economics, not just technology

Wyomo’s decision to provide a complete driverless ride for the general public is what the company believes it can do safely. The question now is how quickly it can scale its service nationally and ultimately globally. It is a question of economics as much as it is a question of technology.

The company could lose tens of millions every quarter – perhaps millions of dollars. A large part of Vemo’s losses are due to the development costs of Vyomo’s technology. But it is a safe bet that paid Vemo One rides have lost Vemo’s money. WiMo’s safety drivers probably make at least one Uber or lift driver, and the company also has fleet support staff to monitor vehicles remotely. And every Wemo vehicle has expensive sensors and computing hardware that are not present on a typical Uber or lift car.

Eliminating the safety driver is an important step towards making Vemo’s service profitable. But that may not be enough on its own because Waimo says the car still has remote observers.

These VEMO staff never drive vehicles directly, but they send high-level instructions to help vehicles get out of difficult situations. For example, a VEMO spokesperson told me, “If a VAMO vehicle detects that the road ahead may be closed due to construction, it may request another part of our fleet’s response experts’ eyes.” The fleet response specialist can then confirm the road is closed and instruct the vehicle to take another route.

“Multiple cars at once”

The main question for the profitability of WiMo rides is that the proportion of vehicles is relatively opera operators. Wimo may not change profits if there is an operator for each vehicle in the vehicle. But if a serviceable operator can monitor multiple vehicles, the service of two or three vehicles initially and eventually 10 or 20 vehicles per operator becomes more efficient.

“Fleet responders are trained to inspect multiple cars at the same time, but we do not share exact numbers,” said Ars, a spokesman for Vemo. But we can expect that this is the main focus for Waimo in the coming months: to reduce the amount of remote monitoring required for each vehicle so that Waimo can reduce its timely back-office fee support costs.

One important thing to look at here is how fast Momo expands its service to additional customers in the existing service area. In Thursday’s blog post, Wimo wrote, “We’ll start with people who are already part of Wemo One and, over the next few weeks, connect more people directly to the service through our app.” This could mean that Vemo’s service will be available to everyone in its service area in a few weeks. Or Wimo may just be slowly expanding – which could be an indication that Wimo’s service is still not very beneficial.

Before the epidemic broke out in March, “we were doing a total of 1,000 to 2,000 weekly rides, five to 10 percent of which were completely driverless,” a Wyoming spokesman told Arsen. Wimo said it expects to return to the volume of about 100 driverless rides in the week before the end of the year and then grow from there.

Expansion plans

The other big question is how long it takes to expand the coverage area – and how expensive it is. There are three steps for a mom to expand into a new field. First, the company creates detailed maps of the new territory. The company then has its car drive routes in the area with its car safety drivers to test how its software works. Finally, once the company is satisfied with the performance of the software, it starts operating driverless.

It took Vemo more than three years to complete the process for the initial 50-square-mile service area around Chandler, Arizona. Naturally, if one wants to create a national or even global taxi service, Vemo will need to speed up the process dramatically. The next 50 square miles – or even 500 square miles – probably won’t take as long as the first 50.

Expanding the Wamo Forest service step to other parts of suburban Phoenix should be straightforward. Wyoming will easily expand throughout the year into wide roads, a few pedestrians and other southwestern cities with sunny weather.

Rain, snow, humans …

Expanding to other parts of the United States can be difficult. Larger urban centers such as San Francisco, New York, and Chicago have a much higher density of vehicles, pedestrians, bicycles, and other obstacles, except for the Phoenix suburb. Northern cities such as Boston and Minneapolis experience heavy snowfall. Almost every metropolitan area receives more rainfall than Phoenix. It may take more years to bring Vemo technology to these areas.

Vemo also has to deal with differences in law and customs. Different states have different laws on things like right-turn at red lights. Wemo has to make sure it complies with the law in every area. WiMo will also need to tune its vehicles so that its driving style is compatible with local drivers.

Still, if WiMo can at least make its feature available in the Phoenix area, it could be a big advantage over its competitors. Running a large-scale taxi service in a single metro area will give Wimo a wealth of sensor data and operational personal experience that will inform the company’s efforts to reach other regions. Wimo is far from winning the national driverless technology race. But he is clearly an industry leader.