“It will let the public know that it is transparent, that it is not political,” said Dr. Victor Dzau, president of the academy, who told Collins his organization was ready for the task. “The American public will want to know how they are making that decision. Why am I not making it first?”

The administration is making moves that experts applaud, such as turning to top health officials and industry experts to lead vaccine plans instead of politicians, but are still concerned that the overall effort, dubbed Operation Warp Speed, remain hidden. And the administration’s response to the rest of the pandemic has not inspired confidence.

“It is handled like a secret weapon, which is never a good thing,” said Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “Transparency is always good.”

First in line

Once a vaccine is approved, all Americans will not be able to get it right away. That sets up the difficult task of deciding, in the midst of a deadly pandemic, who is most vulnerable to the disease and who is most essential to inoculate quickly.

“People are a little uneasy about the government making the decisions here,” NIH Dr. Collins told a Senate panel earlier this month.

Experts will need to consider vulnerable populations, such as those in life-assistance centers or prisons, people working indoors, such as meat packing plants, and how to assess Americans with pre-existing conditions.

The National Academy of Medicine hopes to have its recommendations available to the public in August or September.

A second panel of vaccine advisers for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), is also developing a set of guidelines. It is not yet clear whether management will select one set of recommendations over the other, or whether they will consider both when making their final decisions.

Last month, the ACIP met electronically in a notorious meeting to discuss who is considered an essential worker, where teachers should be on the priority list, vaccinations for pregnant women, and whether race and ethnicity should be considered. counts priority considerations.

“If we do not address this issue of racial and ethnic groups as a high risk in prioritization, what comes out of our group will be viewed with much suspicion and with great reserve,” said panel chairman José Romero. .

The meeting outlined the steps the government is already taking to prepare for a vaccine, as well as the secrecy that still affects the effort.

Dr. Matt Hepburn of Operation Warp Speed kicked off his presentation on the development of the coronavirus vaccine by asking the panel to note its “inability to provide many details about what we are doing.”

Minutes later, he insisted: “We are not a secret organization that works with unknown people and nobody really understands what we are doing.”

A senior official with the Department of Health and Human Services told CNN “we know there is a problem” when it comes to transparency around Operation Warp Speed.

“Transparency is the key to acceptance,” said the official. “People need to believe in the safety and efficacy of these vaccines.”

‘A huge task’

Vaccine experts are already beating the Trump administration for selling an unrealistic timeline to the American people.

“I think when people tell the public that there will be a vaccine by the end of 2020, for example, I think it will seriously harm the public,” said Ken Frazier, chief executive of pharmaceutical giant Merck, in a statement. recent interview with Harvard Business School. “We don’t have a great history of rapidly introducing vaccines in the midst of a pandemic. We want to keep that in mind.”

Spreading false hopes and failing to do so is just one of the things that could further damage public confidence.

“You can’t give an optimistic message that the vaccine will be developed in December and then, in December, it doesn’t have a vaccine. So people wonder what happened,” said Vijay Samant, a vaccine expert who oversaw production. of three successful vaccines when he worked at Merck. “In the meantime, you know, they’ve given up on social distancing on the assumption that the vaccine will take six months, and people are amazed at what’s going on, they lose confidence.

Once a vaccine is available, it could still take anywhere from six months to a year to vaccinate the population long enough to delay the spread.

“That’s if you’re lucky,” said Samant.

The Trump administration is trying to streamline that process with Operation Warp Speed. It has partnered with vaccine developers to begin manufacturing and storing their medications before safety trials are completed or the Food and Drug Administration has approved the vaccines.

“We are literally making the vaccine on a commercial scale now as we move forward in clinical trials,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told CNBC on Wednesday. “We are doing that at risk, using all the power of the United States government and our financial resources to do that. No one has done this before.”

Once a vaccine is licensed, the goal is to implement it immediately. By next year, the administration expects to have approximately 300 million doses of the coronavirus vaccine available. Any vaccine that is available will likely require an initial dose followed by a second booster injection, experts and vaccine providers said.

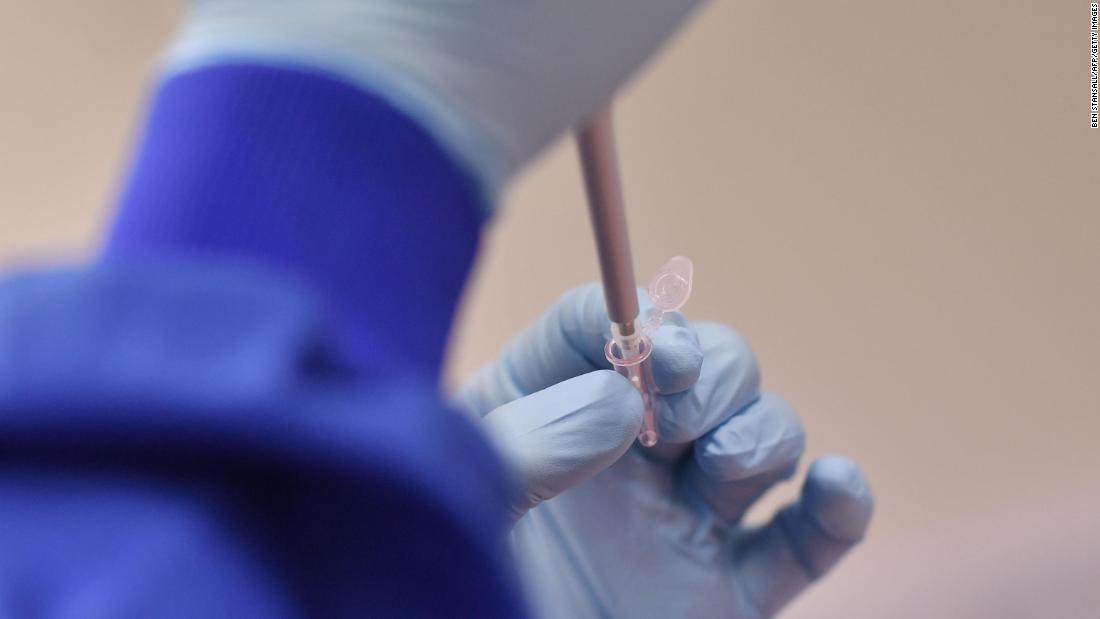

Once a vaccine is ready, it’s still hard to get into the arms of Americans from the lab. The United States government is already spending hundreds of millions of dollars for supplies like glass vials and syringes.

“We, right at the beginning of Operation Warp Speed, are working to block the filling and finishing capacity, as well as the syringes, needles, and glassware, so we’ve secured it so that we can make sure we can vaccinate the American people once we get vaccines that are proven to be safe and effective according to the FDA approval or authorization standard, “Azar told CNBC.

While the Trump administration has awarded some contracts to suppliers with a short track record, others have gone to major manufacturers such as Corning Inc.

“I think the US has set a standard and the rest of the world is following the pattern, actually quite closely,” said Brendan Mosher, vice president and general manager of Corning Pharmaceutical Technologies.

“Glass will not be the critical bottleneck,” said Mosher. “There will be a long way to go when the vaccine is ready, so I think we will be in very good shape.”

Beckton, Dickinson and Company, the world’s largest syringe maker, said the United States is also making progress in obtaining supplies of syringes. But it may still live up to the 700 to 800 million syringes it will need to provide vaccines.

“We understand this is a process, right? And the federal government is making some initial orders with us and other manufacturers, but I think it is the beginning of the process,” said Elizabeth Woody, vice president of public affairs. to the company.

The government has already ordered 190 million syringes from Beckton, Dickinson and Company, while partnering with them to expand their manufacturing capacity.

“What it tells us is that we are now taking the necessary steps to prepare for a potentially seasonal Covid vaccine, as we have done for the flu,” Woody said.

The CDC and the Pentagon are working together to administer the vaccine across the United States, although they have not offered much detail on how they plan to do so.

“This is a big task, even if you have a vaccine, vaccinating these people is a huge task, a huge task,” said vaccine expert Samant. “Because you need to convince people.”

Are we the guinea pig?

Providing a vaccine is one thing. Convincing Americans to take it is another.

Administration officials have publicly criticized guarantees that the vaccine will undergo extensive testing to demonstrate that it is safe and effective. Still, a CNN poll in May found that a third of Americans said they would not receive the coronavirus vaccine, even if it were affordable and widely available.

Some Americans are skeptical of all kinds of vaccines. Others are wary of the safety of the coronavirus vaccine in particular, as it is being produced in an accelerated timeline. For others, the vaccine effort is colored by politics.

“You are seeing people commenting ‘I can’t trust anything Trump says.’ There are people on the opposite end of the spectrum who say, ‘Unless he says it’s okay, I’m not going to do it,'” Emily said. Brunson, associate professor of the state of Texas and co-author of a recent report. on public confidence issues around the coronavirus vaccine. “It’s going to make people who hesitate and who don’t normally vaccinate vaccinate.”

The main concern is to convince minority communities that have experienced higher rates of hospitalization and fatality to get vaccinated. Experts said it will have to involve community outreach through organizations that people already trust, such as faith-based organizations.

“There is a lot of work to be done to make sure we hire them sooner to earn their trust,” said Dzau of the National Academy of Medicine. “There are two ways that people can see it. One is, are we the guinea pig? Or, two, should we get it first because we are more at risk.”

The Trump administration is already imagining a communications campaign to try to win over Americans, a senior HHS official said. The effort is expected to include television, radio, digital and billboard ads.

Next month, the administration plans to begin filming one-minute announcements featuring the administration’s top scientists, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Surgeon General, Dr. Jerome Adams, CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield and others. In the announcements, doctors will answer socially estranged questions from celebrities, musicians, and athletes about concerns about the coronavirus ranging from testing to therapeutics and the vaccine.

Experts say those efforts cannot come soon enough.

“We have this time frame,” said Monica Schoch-Spana, principal investigator for the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Safety, who also co-authored the report on public confidence and the coronavirus vaccine.

“It is not an inevitable conclusion that it will go well,” Schoch-Spana said. “And it is not an inevitable conclusion, it will go wrong.”

CNN’s Ellie Kaufman, Cat Gloria, Austen Bundy, and Daniella Mora contributed to this report.

.