[ad_1]

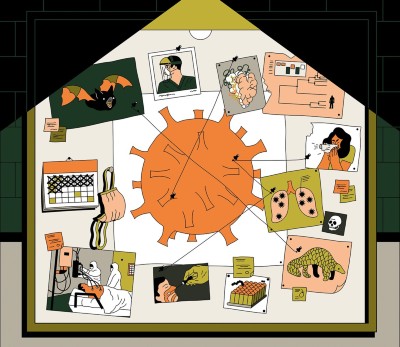

As scientists work to understand the biology of the coronavirus that has infected millions of people worldwide, economists are struggling to make sense of the dramatic effects of the pandemic on world economies.

The unprecedented situation is causing many economies, including that of the United Kingdom, to contract faster and deeper than at any other time in the last century. Researchers at the Bank of England, which is charged with maintaining a stable financial system in the United Kingdom, including setting the country’s interest rates, are among those studying the impacts of the coronavirus on the economy to come up with the answer. bank policy. The crisis is leading the bank’s researchers to look beyond their usual data sources and learn from other disciplines, including bringing together models of economics and epidemiology to make sense of the interaction between financial systems and the virus.

Arthur Turrell, a trained plasma physicist, works in the bank’s main data science unit, which guides the institution’s policy. Turrell is one of the bank’s more than 200 researchers who hail from a variety of scientific disciplines, including linguistics, computing, and mathematics.

Talked with Nature on how his team is mining new sources of data to track the real-time effects of coronavirus on the economy, and explore its long-term impacts.

How has the coronavirus pandemic changed your research?

The coronavirus has completely changed my approach. A major effort, which has fueled a change that was already underway, is to provide better monitoring of the current situation in the economy to support policy makers at the bank.

Typical macroeconomic data points, such as figures on gross domestic product (GDP), come out every quarter. That’s fine in normal times when the changes are quite gradual, but now the changes happen week to week. And with policies like the blockade, it’s as if entire sectors of the economy have been turned off overnight. So we have had to think very differently. We have been using information science and computer science tools to automatically collect and analyze data as soon as it comes out, and turn it into a report for bank policy makers. We use a little machine learning and more sophisticated tools for text analysis.

What kind of data are you using?

We’ve looked at things like restaurant reservations, the use of public transportation apps, flight data, electricity usage, and indicators of the number of people visiting certain places. The job posting website Indeed shares your data with us about the ads that companies post. So we can see that there has been a huge drop in the demand for workers, with less than half of the jobs posted each day than might be expected. The data does not have the same level of quality as, for example, a series from the UK Office for National Statistics. However, the fact that it has such a rich granularity means that it is useful in a different way.

What kind of research are you doing on the pandemic?

One of the most important things to understand is the interaction between macroeconomics and disease progression. I am involved in a project that is trying to merge macroeconomic and epidemiological models to understand the relationship between the virus and the economy.

We start by taking a very simple macroeconomic model and a very simple epidemiological model and we basically put them together. The type of modeling used in epidemiology, called compartment models, studies the dynamics of infectious diseases by dividing the population into groups, such as people susceptible to the virus, infectious or recovered. It is not so familiar to economists, but it could be more familiar to those of us with a scientific background.

We have advanced further in that type of model to combine macroeconomics and epidemiology, but I am also looking to use an ‘agent-based’ modeling framework, which explains the behavior of a system by simulating the behavior of each individual agent in that. Unlike science, in economics these are somewhat controversial, but I think they have real promise for this type of interdisciplinary problem.

What can these models tell you?

We are really interested to know if we can say something about how people’s economic choices can change their risk of coming in contact with the virus. So, for example, let’s say the closure is over and I decide to go to a restaurant. All things being equal, am I more or less likely to participate in that economic activity, if there is still a small chance of infection? You may think it is less likely to do so, and that is an economic impact of the virus. Perhaps people who have long-term health consequences from the virus will not be able to work the same way as before, or we could have many people who work from home.

What are the biggest unknowns in terms of how the pandemic will affect the economy?

We are always interested in unemployment and the way to any recovery from confinement. Once parts of the economy are reopened, will everything quickly return to normal? Or will it take a little longer? And will there be long-term consequences? We think that the UK economy has a potential size, and one question is whether some of those potential changes, due to a “scarring” effect.

One of the things that particularly interests me is the heterogeneity in well-being between different ages and different types of workers. Take a worker who is fit and young and who may be able to work remotely. This will have affected them very differently from someone who is a little older and has a higher risk of more serious health outcomes if they contract the disease, or someone who has a health care job that exposes them to high risk.

How will the interaction between health and economic activity affect the economy?

People’s well-being is greater if they have less risk of contracting this terrible virus. So one question is, will the type of work people do change?

Imagine that I am someone who can choose to work more hours or less hours. If my job gives me any chance of getting the coronavirus, will I choose, other things being equal, to work fewer hours? And will aggregate hours across the economy capture that effect? If I choose to work less, I will probably have to spend less, and my expenses are someone else’s income, so that can lead to different results for other people.

This interview has been edited for its length and clarity.