[ad_1]

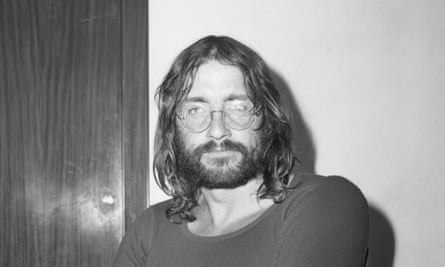

Doug Scott, who died of cancer at age 79, was the first Englishman to climb Everest, but it was what happened afterwards that made him famous in the mountaineering world.

Scott and his Scottish partner, Dougal Haston, were part of Chris Bonington’s 1975 expedition to climb Everest the “hard way,” through the southwest face. Having left their upper camp shortly after sunrise, the pair faced testing delays as Haston’s oxygen equipment got cold and unconsolidated snow, chest deep in places, slowed their progress. It was already 3.30pm when they finally reached the lower south summit where the two climbers stopped to melt the snow and have a much-needed drink.

Should they continue? Haston suggested stopping for the night, but Scott thought it best to go ahead and do it. Two hours later, around 6 in the afternoon, they were at the top.

Scott was exulting, and despite the late hour, he spent time gazing at the view before descending. When they regained the southern summit, their headlights had broken down and it was too dark to continue. With the bottled oxygen finished, Haston and Scott faced a brutal night of hypoxia and cold. No one had ever spent a night at this height. Worse still for Scott, he had left his feather suit behind because it was too tight to climb on. They battled hallucinations and the threat of hypothermia all night, but both survived without frostbite and were able to descend at first light.

Scott’s reputation for physical stamina and mental strength only improved two years later, following the first ascent, this time with Bonington, of the fearsome Karakoram peak known as the Ogre. As he rappelled down from the top, Scott slipped and collided with a rock wall, breaking both legs. Abandoned at 7,200 meters beyond rescue, on a mountain of considerable difficulty, Scott crawled on his knees back to base camp through a storm, aided by his teammates Mo Anthoine and Clive Rowland. It remains one of the great survival stories of world mountaineering.

It is understandable that such famous stories of human hardship and resistance sometimes overshadowed the complexities of a man who saw his life in the mountains as part of a spiritual journey, studied Buddhism, and dedicated his last years to helping the people of Nepal.

The son of Joyce and George Scott, Doug was born in Nottingham on May 29, the date Tenzing and Hillary would climb Everest 13 years later. George was a notable policeman and boxer, in 1945 the British amateur heavyweight champion, but he gave up his Olympic dream to focus on his family and take care of his assignment. Doug inherited his father’s powerful body and green fingers, growing organic food wherever he settled.

Many climbers in Scott’s generation found childish inspiration in the 1953 Everest expedition film, but Doug was a restless child, annoyed at not staying still when his class was brought to see him. His route to Everest began more with exploring his own neighborhood, building dens or wandering around with friends. School was too boring when there were adventures to be had, but, having failed the 11th or higher, and having shown what it was like to work in one of the local coal mines, he rushed to study modern high school, taking additional classes and discovering a love affair. for reading. He went on to primary school and to Loughborough for teacher training.

Scott discovered climbing during an Easter scout camp in 1955, when he saw men climbing Black Rocks over the Derwent Valley. He was instantly captivated. Fifteen days later, he walked the 20 miles back from Nottingham equipped with his mother’s clothesline. Big and broad-shouldered, Scott was full of energy.

Married in his 20s to Jan Brook, during the 1960s he juggled a teaching career (often taking his children to the hills), a growing family, rugby and rock climbing. There were exploratory expeditions with a group of friends from Nottingham, first to the Tibesti Mountains of Chad in 1963 and then in 1965 to the Hindu Kush of Afghanistan, traveling overland by truck.

By the late 1960s, Scott had earned a reputation for being an “auxiliary” climber, driving pegs into the rock and hanging from them where needed, thus making the first ascent of the Scoop, Strone Ulladale’s wildly jutting cliff at the Isle of Harris; as well as several difficult ascents in the Dolomites and the Troll Wall in Norway.

He also discovered Yosemite, climbing with American star Royal Robbins and then making the first European ascent of El Capitan’s Salathé Wall with Austrian Peter Habeler. The carefree California scene appealed to Scott; He tasted acid, once and rather by accident, and it became a less self-absorbed way of life, something that would only deepen when he discovered the Himalayas and more mystical ways of seeing.

By then he had stopped teaching, had been denied leave of absence to climb Mount Asgard on Baffin Island, and made a living as a builder. One morning in February 1972, in the bathroom, he received a call from Salford climber Don Whillans inviting him on an international expedition to the southwest face of Everest. They would go to Nepal in a few weeks. “I don’t think so,” Scott wrote in his memoir Up and About (2015), “if I had remained a school teacher, Don would have invited me to go.” The expedition was tense, but Scott discovered his true environment, the otherworldly and physically punishing world of high altitude mountaineering.

With a strong performance, he was asked about Bonington’s first attempt in the fall of 1972, beginning an intense period of cooperation that saw them climb Changabang in the Indian Himalayas before successes at Everest and Ogre. Then in 1978, in the middle of an expedition to K2 and after the death of a teammate, Nick Estcourt, in an avalanche, this productive relationship ended, although the two would later reestablish their friendship.

There were many more expeditions, including more attempts at K2, but Scott’s biggest climb was arguably a demanding new route up to the world’s third highest mountain, Kangchenjunga, climbing without bottled oxygen and with only four on the team. Climbing style had become increasingly important to Scott, the path being more important than the finish line.

This reflected a growing spiritual interest, sparked in part by his discovery of Buddhism as a schoolboy, a discovery that deepened as he explored the Himalayas. Milarepa, the 11th century Tibetan teacher, was an inspiration. So was the mystical philosopher George Gurdjieff. After having a series of intense, out-of-body experiences in the mountains, it was perhaps not surprising that Scott found himself a seeker.

Always generous with his friendship, as he entered middle age, Scott became a mentor to the younger generations inspired by the idea of light climbing and the ideas he embraced. Bonington called him “a tribal chief”. And when his climbing career ended, he served on committees and was president of the Alpine Club, championing what he saw as the ethical soul of the sport.

The most important thing for him was helping the communities he met on his expeditions to the Himalayas, pouring immense energy into the charity he founded in 1989, Community Action Nepal (Can). This was initially established to improve working conditions in tourism, but later had broader development goals with a significant budget. It was typical of Scott that he should use his latest illness as a last chance to raise money and raise awareness about CAN’s work, with a sponsored climb of his ladder.

Scott was divorced twice. He is survived by his third wife, Trish (née Laing), whom he married in 2007; of three children, Michael, Martha and Rosie, from his first marriage, with Jan; and two sons, Arran and Euan, from his second marriage, with Sharu (nee Prabhu).

• Douglas Keith Scott, mountaineer, born May 29, 1941; died on December 7, 2020