[ad_1]

Scientists have created a super enzyme that breaks down plastic bottles six times faster than before and could be used for recycling in one to two years.

The super-enzyme, derived from bacteria that naturally developed the ability to eat plastic, allows for complete recycling of the bottles. Scientists believe that combining it with enzymes that break down cotton could also allow mixed-knit clothing to be recycled. Today, millions of tons of this type of clothing are dumped in landfills or incinerated.

Plastic pollution has polluted the entire planet, from the Arctic to the deepest oceans, and people are now known to consume and breathe microplastic particles. It is currently very difficult to break down plastic bottles into their chemical components to make new ones from old ones, which means that every year more new plastics are created from oil.

The super-enzyme was engineered by joining together two separate enzymes, both of which were found in the plastic-eating insect discovered at a Japanese waste site in 2016. Researchers revealed a engineered version of the first enzyme in 2018, which began to break down plastic in a few days. But the superzyme works six times faster.

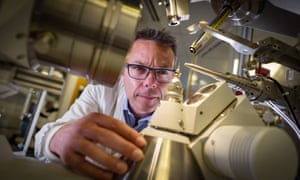

“When we linked the enzymes, quite unexpectedly, we got a dramatic increase in activity,” said Professor John McGeehan, University of Portsmouth, UK. “This is a trajectory towards trying to produce faster enzymes that are more industrially relevant. But it’s also one of those stories about learning from nature and then taking it to the lab. “

The French company Carbios revealed a different enzyme in April, originally discovered in a pile of compost sheets, that degrades 90% of plastic bottles in 10 hours, but requires heating above 70 ° C.

The new superenzyme works at room temperature, and McGeehan said that combining different approaches could accelerate progress towards commercial use: “If we can produce better and faster enzymes by linking them together and supplying them to companies like Carbios, and we work in partnership, it could start to do this within the next two years. “

The 2018 work had determined that the structure of an enzyme, called PETase, can attack the hard, crystalline surface of plastic bottles. They discovered, by accident, that a mutant version worked 20% faster. The new study looked at a second enzyme also found in Japanese bacteria that doubles the rate of breakdown of the chemical groups released by the first enzyme.

Bacteria that break down natural polymers like cellulose have developed this twin approach over millions of years. The scientists thought that by connecting the two enzymes together, it could increase the rate of degradation and allow them to work more closely.

The bound superzyme would be impossible for a bacterium to create, as the molecule would be too large. So the scientists connected the two enzymes in the lab and saw a further tripling in speed. The new research by scientists from the University of Portsmouth and four US institutions is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team is now examining how enzymes can be modified to work even faster. “There is huge potential,” McGeehan said. “We have several hundred in the lab that we are currently joining.” A £ 1 million test center is now being built in Portsmouth and Carbios is building a plant in Lyon.

Combining the plastic-eating enzymes with existing ones that break down natural fibers could allow the mixed materials to be fully recycled, McGeehan said. “Mixed fabrics [of polyester and cotton] they are really difficult to recycle. We’ve been talking to some of the big fashion companies that produce these textiles, because they’re really struggling right now. “

Activists say reducing plastic use is key. Those who work in recycling say that strong and light materials like plastic are very useful and that true recycling is part of the solution to the problem of pollution.

Researchers have also managed to find insects that feed on other plastics, such as polyurethane, which is widely used but rarely recycled. When polyurethane breaks down, it can release toxic chemicals that would kill most bacteria, but the identified bug actually uses the material as food to power the process.