[ad_1]

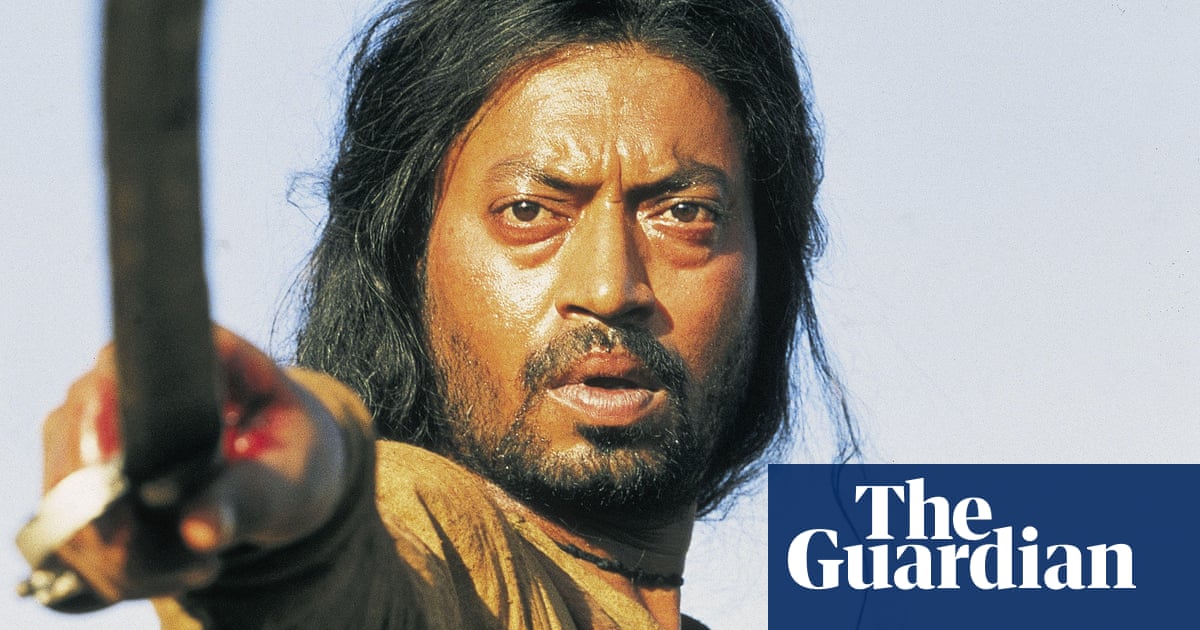

I first met Irrfan Khan 21 years ago at a cheap beach hotel in Mumbai. I was 28 years old and I was presenting my debut film, The Warrior, about a conflicted executor in feudal India. None of the actors I had seen were right. I would tell them that I wanted to do a western, a mix of Robert Bresson and Sergio Leone, and their eyes would shine.

They weren’t interested in making a movie without songs or romance or a lot of dialogue, shot far away in Rajasthan and the Himalayas. A film that was not typically British and was shot in Hindi, but was not entirely Indian either.

Irrfan entered the room and at that moment I knew he was right. He had an incredible presence and a beautiful face and unusual puffy eyes. He loved world cinema, he had the tone and the references and he liked the challenge of telling a story without words.

Then I said to my friend Amit, who I was pitching with, “He looks like someone who killed a lot of people, but he feels really bad about it.” The only problem was that he looked like such a wonderful and warm guy that we had to toughen him up a bit. That was part of the fun. He was 34 years old and looked better and fitter as he aged.

We went to the desert and mountains for filming and saw snow for the first time. It was very low budget and pre-digital, so there was no room for playback or maneuvering. You just watched him take a shot and then you said, “That was amazing! Ok go on!

Before that, Irrfan had been thinking about stopping acting because he was getting bored. He had not been offered a role that would allow him to demonstrate his great gift, which was to say it with just a glance. Raised simple lines to brilliant cinematic moments, it could make you feel something very complex and emotional by doing very little. He was a true movie star.

Over the years, the cast and crew of The Warrior kept in touch and had meetings, which is quite unusual in this business. There was a real connection, and Irrfan, touching, tall, elegant, a bit of another world, was our spiritual leader.

Even before he was famous, he had immense dignity and charisma. Some actors can be quite common when they are not ready. He didn’t have to be in disguise. Even when people didn’t know who he was, in a store or walking down the street, they stopped and looked. Once we were on a flight together, in economy, and every five minutes, the stewardesses appeared to ask him if he needed anything.

The Warrior won Baftas and the Sutherland Prize for Best First Film at the London Film Festival; The next day we went to lunch at my mother’s house in Hackney. Miramax bought the American rights, but Harvey Weinstein put the film on a shelf for years, which killed her. And he was disqualified from the Oscars foreign language category, which also upset Irrfan; he was not without ambition.

But we both noticed each other and he made movies with Danny Boyle, Michael Winterbottom, Wes Anderson and Ang Lee. I worked with David Fincher recently and asked him how he had come across me. He said, “Oh, my best friend came over with a DVD and said he had to see it.” It turned out to be Brad Pitt, and the DVD was Senna. I think Irrfan told Pitt to watch it when they worked together on A Mighty Heart.

No matter what the movie is, I always felt that Irrfan was the best and the most credible, because he was very honest: everything he did had a soul and truth. When his career took off, he remained the same. It had always been international and international, that’s why it could work without problems in so many genres and countries.

Fame never changed him. We try to meet every time he was in India or he was in London. We would talk movies and go to the British Museum and Primrose Hill and our children would play soccer together. When I was receiving treatment here, I would visit him in the hospital and we would go to the local park or cafeteria, or he would come to our house. He talked about his disease in a way that he had never heard anyone talk about cancer before. He was extremely inquisitive and wanted to understand exactly what was going on.

In 2018, I invited Irrfan and his oldest son to an early cut of my Diego Maradona documentary. “Why did you do this Movie? “He asked in the editing suite a few days later.” What does this movie say about you? “His notes were really tough! I wanted him to make the movie more personal; about me and Maradona. They were good notes. Irrfan knew me well enough to say that he didn’t like that cut, but he didn’t want to tell me in front of 50 people.

He returned to India and we send messages from time to time. Sometimes he responded and sometimes his wife, Sutapa. It is difficult when a friend lives on the other side of the world. The other week I found some photos from that first casting session at the dubious hotel in 1999 and sent them to him. Sutapa responded by saying, “Oh, he’s wearing his lucky black shirt.”

In the spring Irrfan sent me a photo of his new calf. He always told me to go visit his farm on the outskirts of Mumbai; I never got there. You always think there is time and then you run out of it. He and I were very in sync for a while, in part I think because the movie we made was a little out of step with the rest of the world. It didn’t fit perfectly, and neither did we.

It is like losing a brother. He used to call me at 2 in the morning and I would worry that something bad had happened. “Oh no,” he said, “I just missed you and wanted to chat.”