[ad_1]

OROn April 9, 1970, a press release was sent to the media about a 27-year-old solo artist. Taking the form of a Q&A, most of it explained what their debut album, McCartney (“home, family, love”) was about. Then, almost as an afterthought, came this: “Are you planning a new album or single with the Beatles?” “Not.” “Do you anticipate a time when Lennon-McCartney will become an active songwriting association again?” “Not.”

Paul McCartney never said in person that the Beatles had split, but these responses told reporters everything they needed to know. “Paul leaves the Beatles,” the Daily Mirror front announced the next day, as the story rebounded around the world. Here, exactly 50 years later, we talk to Beatles fans and connoisseurs about the day when the story that defined the band’s era finally came to an end.

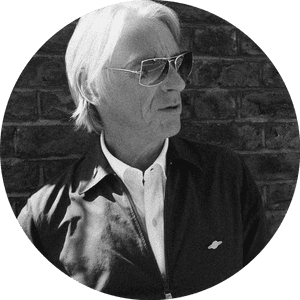

Paul Weller: “They were my entire universe”

Then: 11, college, Maybury School, Woking. Now: 61, musician

My mother had a part-time job in the local newspapers and I remember seeing a headline: “Paul, I quit” that fateful day. I couldn’t understand it. I was devastated The Beatles were my entire universe.

Now I see it as inevitable and also necessary, because in hindsight they couldn’t have continued until the 1970s. It wouldn’t have felt right. Bowie took his place, I think. But I also wonder what would have happened if they had continued. Would there have been 50 years of OK or crappy records to lessen their meaning and impact? Would they still be as important as they are now and always will be?

The Beatles will always be my guides. They were my four northern prophets. They came to show us that there is another way of living, and to rejoice in what we have.

Paul Weller’s 15th solo album, On Sunset, is released June 12 on Polydor.

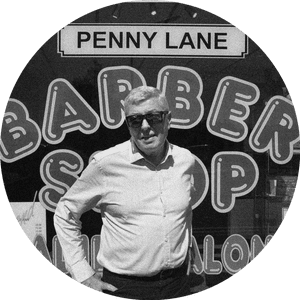

Annie Nightingale: “They weren’t pop stars anymore”

Then: 30, journalist and DJ Radio 1. Now: 80, Radio 1 DJ

I witnessed the collapse at hand. I was friends with Apple, the band’s label, one of the few who entered the sacred halls. He had been a journalist and television presenter, so he knew the band well. They also helped me get my first job on Radio 1 that February. But I felt like everyone was papering the cracks.

Apple had been this utopian dream. The band wanted to share the fruits of their successes caring for other groups, but they had been so vulnerable and lost since [their manager] Brian Epstein died. They weren’t really pop stars in 1970. They were artists. But they were still extensions of who they had been at first: the young people who told you you didn’t have to be like your parents for the first time.

I remember that it was a very sad day and that I was very concerned that the hard-earned land they had built would be lost. We really didn’t want the establishment to return.

Annie Nightingale’s memoir, Hello, Hello, is published on September 3 by Hachette.

Bonnie Greer: “I moved to the UK because of them”

So: 21 years old, history student. Now: 71, writer, broadcaster, administrator emeritus of the British Museum, OBE

He was only 21 years old when Paul McCartney announced that he would be releasing a solo album and, by the way, the Beatles were breaking up. They had been a part of my life since they came to the Ed Sullivan Show six years earlier. I can still see the curtain open after the rather stiff old man announced them, and there they were. I heard on my transistor a black radio show, Herb Kent the Cool Gent, which was generally just Motown and soul. One day the opening chords of Paperback Writer started, and everything changed for me.

It had been a black girl growing up on the south side of Chicago, in the civil rights movement, the black student movement, Bobby Kennedy, everything, but then there was the Beatles. They gave me agency. I moved to the UK because of them. It is strange that it took four Liverpool boys to do that. Despite all their permutations, the Beatles were like Oz or Alice in Wonderland, a passage to another world. When they parted, I knew we were entering another era. And we did it.

Freda Kelly: “The fans didn’t want it to end”

Then: 25, official secretary of the Beatles fan club. Now: 75, part-time legal secretary

There was still a lot going on in the fan club in the early 1970s. By then I had my daughter. My husband worked shifts, so he would drop her off at a daycare, go to the office, and answer many letters. Fans would ask if they were breaking up all the time. I would try to avoid answering.

The breakup had been in the cards for a while. I wasn’t surprised People grow: other priorities emerged, like wives and children. I kept the fan club for another two years, sending old records and press photos. I closed it when I was pregnant again in 1972, then took time off to raise my children. I went back to college and became a lawyer’s secretary. The fans didn’t want him to leave. But I never looked back.

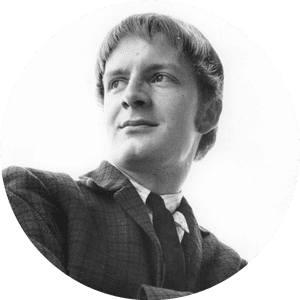

Alan Johnson: “The United States was healed after the JFK assassination”

So: 26, postman. Now: 76, former home secretary, author of In My Life: A Music Memoir

He was the father of three children and lived on council property in Slough. Listening to Abbey Road the summer before, it was obvious that he was getting closer. That side two medley, ending with The End, is all there. I still can’t hear that without tears in my eyes.

It is difficult to impress how much effect they had on society in general. They healed the United States after the JFK assassination. Children in Russia thought of different lives after listening to their music. They released a huge wave of creativity that was paying off in 1970: He was enjoying Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and one of Apple’s own, Badfinger.

They had tempered each other like a band, Paul tempering John’s cynicism, John tempering Paul’s tendency to fantasy. In 1970, as a fan, you knew they wanted to be themselves, and the Plastic Ono Band album in 1969 had made that clear. Still, you thought they might get back together. Until Lennon died, we still think they could.

Mike Vickers: “They had already done everything at that time”

Then: 30, orchestra arranger, operator of Moog on Abbey Road. Now: 80 years old, author of A Week in the Life: Working With the Beatles in All You Need Is Love

I really wasn’t aware that things were getting unreliable. The previous summer, they had been voicing why when I entered the studio, and it sounded sensational. You couldn’t imagine that this was a band about to break up.

I also arranged for the 1967 All You Need Is Love TV show, and learned about Paul from my friend Peter Asher. [brother of Jane, McCartney’s then girlfriend]. Peter said that Paul was one of those people who knew exactly what would happen next when making music. He was correct. He was more than brilliant in the studio and a great leader, although I can imagine how that could have caused stress.

Since they had done everything else at the time, I bet they decided to part ways was the next thing to do. Think about what most artists do in life. They did it and more on their albums in seven years.

Booker T Jones: “I spent all my rooms playing on the jukebox”

Then: 26, leader of Booker T and the MGs. Now: 76, author of My Life, note by note

We launched McLemore Avenue, our tribute to Abbey Road, the same month that the Beatles broke up. Abbey Road had made me want to do more than R&B and work with people like Leon Russell, Quincy Jones and Bill Withers.

You could hear the Beatles desperately trying to be four guys by then. I loved them since I first heard them in college, pouring all my rooms into the jukebox to play. I want to touch your hand. They were also very generous to us on the 1968 Stax tour of the UK. They even sent us a limo! When it was over, it was sad, but it was about time. We were lucky that they made the sacrifice to be together for so long.

Richard Williams: “It didn’t matter, there were tons to listen to”

So: 23, news editor Melody Maker. Now: 73, music and sports journalist.

Sounds magazine had just started and we had lost a lot of staff, so I suddenly became number two in the Melody Maker. I had also become his Beatles persona. John and I had always gotten along pretty well, but he was about to move to Los Angeles. We all knew they were breaking up. To anyone in the business, the Mirror story didn’t really seem like news, just confirmation.

It didn’t matter that the Beatles weren’t around much by then. The Stones either. It was a very dynamic moment musically. There were still tons to listen: heavier things like Led Zeppelin, country-rock like Flying Burrito Brothers, great singer-songwriters, the first glam moves.

The last word about the Beatles didn’t come until John sent us a letter in November 1971, limping the dog out of its misery. [in response to an interview Paul had done in the paper that month, discussing the Beatles’ financial woes]. Using our mail bag to communicate with each other was exciting, but felt quite definitive.

No one thought there would be a reunion tour. On the other hand, rock and roll was not old enough to have reunion tours.

Lillian Adams: “We were going to John’s house on the bus”

Then: 21, Beatles fan since 1961. Now: 71, retired finance editor

I was surprised when I heard that they had separated. He had read that Yoko didn’t like it, Linda didn’t like it, that Paul wanted the Beatles to be cared for by his girlfriend’s father and brother, which surely didn’t seem like a good idea to anyone but him. . But I thought they would get over it. They had been the Beatles since they were children. How could they be anything else?

I had seen them a lot in my teens, living not far from Liverpool. On Saturdays and school holidays, my friends and I went to John’s house on the bus since we had nothing else to do. We only saw it once. You have very little access to pop culture back then. He would get his monthly Beatles magazine, Top of the Pops once a week on TV, but that was it. The idea of seeing your favorite group at any time of any day was incredible.

I discovered a lot of music from the Beatles. I wouldn’t have liked blues without them: I was more interested in John Mayall, Eric Clapton and Cream in 1970. But I still bought all the Beatles albums and loved Abbey Road. He couldn’t believe they wouldn’t be there anymore.

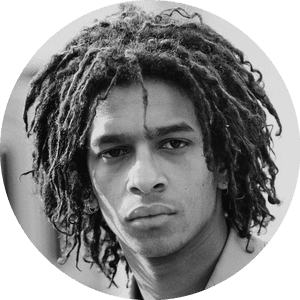

Don Letts: “It was not a bad thing, the first solo albums were great”

Then: 14 years old, schoolboy, Tennison’s School, London. Now: 64, film director and DJ for BBC Radio 6 Music

My older brother Desmond worked on Carnaby Street and brought the Beatles records home. In the late ’60s he had all the Beatles’ bootlegs with the three pigs on the label, and he was a scruffy young man from Apple, hanging around. I eventually had the second largest collection of Beatles memories in the UK, before punk came and saved me. For me, the Beatles laid the foundation for all possibilities in pop.

If he followed the emotional arc of his records, he could tell that things were going wrong. I remember thinking that it wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. Those early solo records were great: John’s raw emotions exposed with Plastic Ono Band; George’s pious work, All Things Must Pass; Paul consistently doing great things.

I also got more into Trojan reggae and the American soul after they broke up; The duality of my existence as a black British person meant that, as one side of that equation wobbled, I entered the other. But even now, Beatles music has an impact on people’s lives. It will live forever.

This article contains affiliate links, which means that we can earn a small commission if a reader clicks and makes a purchase. All of our journalism is independent and in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. By clicking on an affiliate link, you agree that third-party cookies will be set. More information.