[ad_1]

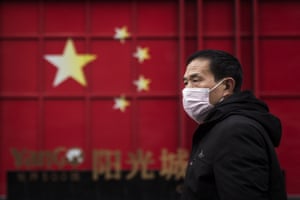

In late December last year, doctors in the central Chinese city of Wuhan began to worry about quarantined patients in their hospitals suffering from an unusual type of pneumonia.

As the mysterious disease spread in one of China’s major industrial centers, some tried to warn their colleagues to take more care of themselves at work, because the disease resembled Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome), the respiratory illness mortal who had killed hundreds of people around the world. region in 2002-03 after a government cover-up.

One of those who tried to raise the alarm, although only among a few colleagues from medical school, was a 33-year-old Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang. Seven people were isolated at his hospital, he said, and the disease appeared to be a coronavirus, from the same family as Sars.

In early January, he was called by the police, reprimanded for “spreading rumors online” and forced to sign a document acknowledging his “misdemeanor” and promising not to repeat it.

Many of the early cases were related to the Huanan fresh produce and seafood market, which also sold wildlife, suggesting that the early cases were hired there.

Scientists would discover that the disease likely originated from bats and then passed through a second species, in all probability, but not for certain, pangolins, a type of scaly anteater, before infecting humans.

But the infections soon spread directly among patients, so fast that on January 23, the government announced an unprecedented closure of Wuhan City and the surrounding Hubei province.

Two weeks later, on February 7, Li, who had contracted the coronavirus himself, died in the hospital of the condition he had tried to raise the alarm about. He had no known underlying conditions and left behind a wife and young child.

Li became the face of the mysterious new disease. The story of his death and photos of him in a hospital bed wearing an oxygen mask made news in the media around the world, including in the UK.

Apparently, the world was becoming increasingly aware of how deadly the coronavirus could be, which was not just another form of the flu with fairly mild symptoms.

But while UK scientists and medical researchers became increasingly concerned and studying the evidence from China, those who were most concerned were not sending their messages to high places.

Distracted by Brexit and reorganizations

Boris Johnson’s conservative government had other more immediate concerns earlier this year.

Johnson was still enjoying his success in the general election last December. After returning from a Caribbean holiday vacation with his fiancé, Carrie Symonds, the political climate for the Prime Minister seemed fair. It was honeymoon time.

Three and a half years after the Brexit referendum, the UK was finally on the verge of leaving the EU on January 31. Fireworks and parties were being planned for the big night, minted the 50p celebration coins.

Certainly, minds were not in a developing health emergency, as Johnson prepared himself to exploit the moment of the UK’s departure from the European Union for all that was worth it. “I think there was overconfidence,” admitted a very important Tory last week.

The Prime Minister and his top adviser, Dominic Cummings, also wanted to leave an early impression at home, as national reformers. Cummings was waging a war against public officials in Whitehall, throwing his weight and deliberately pestering the Westminster apple cart.

While making headlines, reporting on his iconoclastic ambitions, Johnson was preparing a major cabinet shakeup to assert his own authority in other areas, now that Brexit was over and dusted off.

With Labor effectively without leaders after their fourth consecutive loss in the election, there was little opposition to upset Johnson on any front, and certainly none who asked difficult questions about the coronavirus.

The prime minister duly reformulated his cabinet team on February 13, five days after Li’s death in Wuhan. He made major changes but, unsurprisingly, retained the pair of hands so far sure of Matt Hancock as your health secretary.

In a sign of where the priorities lay, and a lack of concern that a possible crisis might be heading east, Hancock wasted no time filming a video of himself smiling happily on the day of the reorganization.

He punched his right fist with his left palm saying he couldn’t wait to “break” and that he was enjoying the opportunity to deliver on the promises of the conservative manifesto, reform social care and improve life sciences. And finally, in a grimmer voice, he spoke of “dealing with the coronavirus and keeping the public safe” before adding, as the smile returned: “Now let’s get back to work!”

It may be too early to conclude with certainty that Johnson, Hancock, and the entire team of government science and medical advisers fell asleep at the wheel. But the fact that Johnson and Hancock, in common with much of the Downing Street staff, either contract the virus or suffer symptoms, suggests that the people at the top had not been alert enough.

Now, 11 weeks after the first cases in the UK were confirmed on January 31, a period during which more than 14,000 people (and probably several thousand more once deaths in nursing homes are counted) in the UK have died of Covid-19 – and With the country blocked, the economy facing a prolonged recession as a result, schools closed and there are no signs of an end in sight. You have to ask difficult questions.

We already know with some certainty that other countries, such as Germany, South Korea, Taiwan and New Zealand, will emerge from this crisis with a much better performance than the United Kingdom. A few weeks ago, government advisers rudely said that less than 20,000 deaths would be “a very good result” for the UK.

As we quickly approach that grim number, many experts now believe that the UK can emerge from this crisis, whenever possible, with one of the worst anti-coronavirus records of any European nation. Once the full count is counted, few expect the death toll to be less than 20,000.

By contrast, on Friday, Germany said it thought it had largely controlled the coronavirus. It had had 3,868 deaths, less than a third of the total in the UK (and Germany’s population, at 83 million, is much higher), having conducted widespread tests for Covid-19 from the start, precisely as the UK has been unable do what.

How, then, did it come to this? How did coronavirus spread worldwide, eliciting different responses in different countries? Did the UK simply ignore the warnings? Or did you simply decide to make different decisions, while others decided to take alternative measures to save lives?

The warnings grow louder

David Nabarro, professor of global health at Imperial College London and an envoy from the World Health Organization at Covid-19, says one thing is for sure. All governments were warned of the seriousness of the situation in early January. Ignorance of the looming danger cannot be an excuse. However, it would not be until the end of March, later than many other countries, that Johnson would announce a complete closure.

“WHO had been following the outbreak since late December and in a few weeks called a meeting of its emergency committee to decide whether this outbreak was a” public health emergency of international concern, “” Nabarro said.

“That is the highest level of alert that the WHO can issue, and it was issued on January 30. It made it clear then, to all countries of the world, that we were facing something really serious.”

Long before the end of January, the WHO had closely followed the growing threat: January 14 was a key day in the spread of the disease to be known as Covid-19. The first case was confirmed outside of China, with a woman hospitalized in Thailand.

A WHO official then warned that person-to-person transmission may have occurred in families of victims, a sign that the disease had the potential to spread rapidly, and, within China, officials were told quietly prepare for a pandemic. .

However, there was little international attention on the day, because Beijing’s dire warnings of a pandemic were made in secret, and a WHO spokesperson withdrew his colleague’s claim.

Officially, China had not seen a new case of the coronavirus in more than a week; The outbreak seemed to be fading. It took another six days for China to publicly acknowledge the severity of the threat, time scientists believed meant that 3,000 other people were infected.

But on January 20, officials announced more than 100 new cases and admitted that the virus was spreading among humans, a red flag for anyone working on infectious diseases. The virus could no longer be contained by finding the animal source of the infection and destroying it.

Two days later, the magnitude of the challenge became apparent to the general public when Beijing locked up millions of people. All transport in and out of the Wuhan metropolis was cut, an unprecedented modern quarantine that would have a huge human and economic cost.

On January 29, the UK would have its first two confirmed cases of the disease. I had little sense that China’s dilemma and its focus, closing life as we know it or seeing the death toll spiral out of control, could be our nightmare in a matter of weeks.

In early February, Donald Trump announced a ban on travelers who had passed through China in the previous 14 days. Europe began conducting tests focused on people with symptoms and travel stories linking them to the disease, but little else.

Apparently Johnson still had Brexit and free trade in mind. Any hint of draconian action to combat the coronavirus that could harm the economy was the last thing he was entertaining.

In a Brexit speech in Greenwich on February 3, he made clear his views on the Wuhan-style blockades. “We are beginning to hear some strange self-righteous rhetoric,” he said.

“Humanity needs some government somewhere that is willing to at least powerfully defend freedom of trade, some country ready to take off Clark Kent glasses and jump into the phone booth and emerge with his cloak flowing like the supercharged champion of the right of the populations of the Earth to buy and sell freely among themselves. “

“Collective immunity”: the UK does it alone

In early March, many academics and scientists made it clear that the approach taken by the United Kingdom was markedly different from that followed by other countries. From South Korea to Germany, governments have invested heavily in expanding testing capacity from the first weeks of the epidemic.

Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore had introduced controls on travelers from infected regions and strict contact tracing to help understand who might have been exposed, inform them, and demand self-isolation. Facial masks became widespread in East Asia, long before it was recommended elsewhere.

Testing and contact tracing have been at the heart of the approach advocated by WHO, so that countries can establish how transmission chains are occurring in order to break them..

Many also took some social distancing measures, banned large gatherings, closed schools or extended vacations, and encouraged those who could work from home. Neither was as extreme as the closure of China, or the European and American blockades that would follow.

Writing in the Observer last month, Devi Sridhar, president of global public health at the University of Ediburgh, outlined the UK’s distinctive approach. “Instead of learning from other countries and following the advice of the WHO, which comes from experts with decades of experience in fighting outbreaks around the world, the UK has decided to go its own way. This seems to accept that the virus is unstoppable and will likely become an annual, seasonal infection.

“The plan, as the chief scientific advisor explained, is to work toward” collective immunity, “which is for the majority of the population to contract the virus, develop antibodies, and then become immune. This theory has been widely used to advocate by mass vaccination against measles, mumps and rubella. The idea is that if the majority of the population is vaccinated, a small percentage can go unvaccinated without cases arising. “

It was not just the United Kingdom whose politicians and scientific advisers were possibly slow to act in the early stages. Other countries, such as Spain and France, were also surprised, but it was the tragedy in Italy that alerted Europe to the magnitude of the threat it faced.

European governments and citizens were forced to consider the reality that in an era of global travel, the thousands of miles that separated them from China meant almost nothing. Thousands of Britons were on vacation in Italy the week it closed. They were recommended to be quarantined upon their return, but their contacts were not recorded by the health authorities or tracked.

Italy and the UK had their first case one day apart in late January, but cases increased faster in Italy. The country may have been unlucky in that carriers of the disease flew to its northern cities and ski resorts rather than to other European capitals.

Whatever the reason, cases and deaths began to rise sharply in northern Italy in late February. Dozens of villages have been locked up since the 21st, but life in the rest of the country continued as usual.

It soon became clear that the problem had not been contained. On March 8, Prime Minister Guiseppe Conti quarantined 16 million people across the north of the country, and the next day extended the blockade to all of Italy.

The measures saved lives, but they came too late for thousands of Italians. The death toll surpassed China, and the world seemed horrified when hospitals were overwhelmed, doctors were forced to choose who should have a chance to use a ventilator and who should die. On March 11, the WHO declared a global pandemic. On March 14, Spain closed and three days later, France followed suit.

But in the UK there seemed to be a greater reluctance to act decisively on the blockades: the ban on mass gatherings and the closure of pubs and restaurants. Government scientific and behavioral science advisers warned ministers that the public could react negatively to draconian measures and would not long tolerate them.

In an apparent show of defiance against the lockdowners, Johnson and Symonds attended the England v Ireland rugby match at Twickenham on March 7. The Cheltenham Festival, attended by more than three days until March 13 by 250,000 runners, was allowed to move on.

Closing: Johnson changes tactics

The tone was about to change. At a press conference in Downing Street on March 12, Johnson, who had said a few days before the first death in the UK that the disease “would likely spread a little further,” suddenly became the issuer of serious warnings. .

His advisers’ previous talk about avoiding blockades and developing “collective immunity” had been banished and replaced by brutal honesty. “I must live up to you,” Johnson told reporters. “More families, many more families, are going to lose loved ones prematurely.” On March 18, just days after Downing Street suggested it was not listed on the cards, the government announced the closure of all schools until notified. Bars and restaurants were ordered closed on March 20. The UK was late in the queue.

A former cabinet minister last week described the change in focus as a “change of direction.” Johnson and his ministers were now, even more than before, hiding and advised by their scientific and medical advisers. Many of these advisers had become increasingly concerned that the United Kingdom had fallen out of step with other countries due to political resistance by ministers to measures that would affect the economy. The observer has been told that at least two high-ranking government advisers were on the verge of resigning before Johnson changed his approach.

The government has been unable to escape the consequences of a major failure in preparation. As hospitals threatened to be overwhelmed before orders were issued to massively expand capacity, ministers came under intense criticism for the lack of protective equipment for front-line NHS personnel, for the lack of fans. for patients in intensive care and for not performing a more extensive test. for Covid-19, particularly among NHS workers.

Lack of preparation and instances of chaotic planning have shocked many inside and outside the NHS.

Last week, Dr. Alison Pittard, dean of the College of Intensive Medicine, the professional body for intensive care professionals, said that the minimum specifications for the government’s own ventilation scheme would produce machines that would only treat patients “during a few hours” . “If we had been told that was the case … we would have said:” Don’t bother, you are wasting your time. That is no use, “he told the Financial times.

Last month, the government failed to meet the EU fan acquisition deadline because, the minister said, an email went unnoticed. The NHS had said that 30,000 more would be needed, Hancock reduced this to 18,000. Pittard said his faculty had been warning for years about the shortage of intensive care capacity and intensive care nurses in hospitals.

Typically, each intensive care patient would have an intensive care nurse present at all times, he said. There was now one nurse for every six patients, although other staff had been reassigned to intensive care units to close the gaps and the new system was working due to heroic efforts. Although she was reluctant to criticize the government, she said that if the school had been heard, “we would not start from this place.” Germany, he noted, has 29 intensive care beds per 100,000 people, compared to six in the UK.

Congressman Tory and former health minister Dan Poulter, who works part-time on the NHS, said that given the sheer scale of the challenge facing the government, “it almost seems wrong to be critical.”

But he believes part of the problem is that insufficient advice has been sought from experienced NHS clinicians who would have warned of PPE problems from the start, of a shortage of ventilators, and told ministers of the urgent need. to evaluate NHS staff.

“An early over-reliance on academic modeling also resulted in a lack of experienced front-line NHS clinicians, in other words, people who truly understand the daily challenges facing our hospitals and health services, from food to Initial Covid. 19 action plan, ”he said. “This has manifested itself, among other things, in the slowness of providing adequate PPE for NHS frontline personnel and in the lack of virus testing for health care personnel in the early part of the outbreak.”

How the scientists reacted

When research on the UK response to Covid-19 is written, there is widespread recognition among experts that this lack of long-term strategic planning will be at the heart of it. There should also be a need to ensure that expert views are conveyed to the government more efficiently and broadly. The possibility of a previously unknown disease spreading catastrophically across the world and infecting millions, after all, is not new.

In fact, there have been many warnings in the past about the viral dangers facing humanity. “Given the continued emergence of new pathogens … and the increasing connection of our world, there is a significant probability that a large and deadly pandemic will occur in our lives,” predicted Bill Gates several years ago. “And it will have the impact of a nuclear war,” he warned, and urged nations to start stockpiling antiviral drugs and therapies. If only.

For its part, the WHO prepared, several years ago, a list of viruses without known treatments or vaccines, diseases that could one day trigger this pandemic and kill hundreds of thousands. Possible killers included nipah disease and Lassa fever, as well as a condition he simply called “disease X,” “a serious international epidemic caused by a currently unknown pathogen.”

As for the most likely nature of that mysterious virus, most models assumed that disease X would behave like flu, says Dr. Josie Golding, the leading epidemic at the Wellcome Trust. After all, influenza had caused so many deadly outbreaks in the past. As a result, a lot was invested in preparing influenza vaccines, she says. “But have we been thinking of other diseases besides influenza that could turn into pandemics? I don’t think we have. There has been a real gap in our thinking. “

Then came the appearance of Covid-19, caused not by an influenza strain but by a coronavirus, in November. Initially, only a few cases stood out, a trend that began to change earlier this year with an increase in the number of sick people infected.

“The report that really caught my attention came out in mid-January,” says epidemiologist Professor Mark Woolhouse of the University of Edinburgh. “He said that 41 cases of this new respiratory disease had now been diagnosed in a small area of China around Wuhan. And that set off the alarms for me.

For Woolhouse, the one-place case group showed that it was not a few people scattered across China who get an occasional infection from an animal like a bat or chicken. “Forty-one cases in a small area at the same time couldn’t be explained that way. I realized that people are not learning this from animals. Actually, they are spreading each other. It was already out of control. “

Ewan Birney, head of the European Institute of Bioinfomática in Cambridgeshire, also pointed out the importance of the new disease at that time. “I assumed at first that this would also burn, probably somewhere in Asia,” he says.

His reasoning was direct. The Sars outbreak that appeared in 2003 in China was caused by a coronavirus and killed more than 10% of those infected. In fact, it killed or hospitalized so many of those who infected the transmission chain from one person to another. It was too deadly for his own good. So I thought that this could happen with this new disease. But it turns out that Covid-19 is much smoother and incapacitates fewer people, so there are no cuts in its transmission. When that became apparent in mid-January, I became very concerned. ”

Then there was the infectious of the new virus. A person with Sars generally begins to show symptoms before infecting other people. That makes it much easier to contain. But this was not the case with Covid-19. The first data from China, again released in January, showed that the virus was spreading to people with only the mildest symptoms, or in some cases without symptoms. This was making the condition very difficult to trace, says virologist Professor Jonathan Ball of the University of Nottingham.

“At that time I realized that this outbreak was going to be very serious,” he added. “I sent a tweet to a colleague in Australia. It just said, “This one is out of the bag correctly.” He sent one back agreeing with me.

Around this time, Paul Nurse, Nobel laureate and director of the Francis Crick Institute, remembers attending a conference where he met Mark Wolpert, director of Research and Innovation in the United Kingdom, the organization that funds a large part of British scientific research. .

“I had just received a text message from a colleague about the outbreak and we began to discuss the implications,” Nurse recalls. “It didn’t take long for both of us to realize that this was going to be very meaningful. It took another two or three weeks to confirm these worst fears, in mid-February. “

By this time, Birney had realized that the virus had a real sting on the tail and could cause serious illness among the elderly and those with other underlying serious ailments. “It was mid-term and I was on vacation with my parents. All he wanted to do was finish the vacation and then take them back to their home in the country where they could stay isolated. ”

In February, sporadic cases of Covid-19 appeared across the country, recalls Tom Wingfield, a clinician and infectious disease expert at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. “These were cases that had been brought to the country, mainly from China or Italy. Then there was an outbreak in Brighton and I realized that the virus had spread to a community there. It was a turning point. “

Britain was still doing quite well in containing the disease by testing, tracing contact, and quarantining those suspected of being infected with Covid-19 at this time. “Then, in March, the government decided to abandon this approach and move from containing the disease to delaying its progress,” says Wingfield. “I would really like to know why the decision was made to drop the testing and follow up contacts.”

Many other researchers also question why the government took so long to react to its warnings. “Part of the problem was that there were other virologists who said this would be like Sars or the flu and that there wasn’t much to worry about,” Ball says. “But Sars happened in 2003. The world is much more connected now than it was then. More specifically, Covid-19 was also much more infectious than Sars. And so it began to appear in many other countries.

“Perhaps some of us should have stood up in front of BBC News and said that many should be petrified because this will be a pandemic that will kill hundreds of thousands of people,” adds Ball. “Ninguno de nosotros pensó que esto fuera algo particularmente constructivo, pero quizás en retrospectiva deberíamos haberlo hecho. Si hubiera habido más voces, tal vez los políticos lo habrían tomado un poco más en serio “.

“No hay duda de que no estábamos suficientemente preparados”, dice la enfermera. “Nos advirtieron hace unos años cuando los informes dejaron en claro que el Reino Unido no estaba listo para combatir una gran pandemia de gripe y no tomamos esa advertencia. Como resultado, quedamos atrapados ”.

Él y muchos otros dicen que una investigación sobre la preparación de Covid-19 de Gran Bretaña tendrá que llevarse a cabo en algún momento, pero enfatizan que esto no debería comenzar hasta que la crisis haya sido tratada en el Reino Unido.

El profesor Ian Boyd, ex asesor científico jefe del Departamento de Medio Ambiente, Alimentación y Asuntos Rurales, está de acuerdo. “Existe un gran peligro de que se mire mucho hacia atrás con los beneficios de la retrospectiva y de meter los dedos en la culpa”, advierte Boyd. “Pero cuando estás en medio de las cosas, tienes que tomar muchas decisiones difíciles de 50-50, y a veces tomas la decisión equivocada. Por otro lado, no hay daño en asegurarnos de que aprendamos tantas lecciones como podamos “.

Las lecciones del resto del mundo …

Boris Johnson, después de su propio roce con la muerte a manos de Covid-19, presumiblemente ya no adoptará la actitud entusiasta ante la enfermedad que siempre ha tenido. Un ex ministro conservador dijo: “Si Boris tuviera algún sentido, tomaría el control de la investigación y la dirigiría”.

Una conclusión que los expertos ya están sacando es que fueron aquellos países cercanos a China, con recuerdos de Sars, o lazos culturales con su vecino, que actuaron mucho más rápido en respuesta a Covid-19. Quizás lo más notable en su éxito fue Taiwán. Estrechamente vinculado por lazos económicos y culturales con China continental, Taiwán podría haber estado en alto riesgo de una gran epidemia de Covid-19. Turistas y empresarios viajaban regularmente de ida y vuelta.

Pero tal vez ayudado por tener un epidemiólogo como vicepresidente, el gobierno estableció un régimen estándar de pruebas y rastreo de contactos que significa que casi tres meses después de su primera infección confirmada, ha registrado menos de 400 casos y seis muertes.

Las extensas pruebas y el seguimiento exhaustivo de los contactos de Taiwán son precisamente el tipo de acción que exige el ex secretario de salud Jeremy Hunt antes de que se levante el cierre del Reino Unido. Hunt señala que es una de las condiciones esenciales establecidas por la OMS para evitar una segunda ola resultante de una reducción de las restricciones.

Hong Kong, que también sufrió la crisis de Sars, también se adelantó para imponer la cuarentena y el distanciamiento social, así como el uso generalizado de máscaras, y hoy ha registrado poco más de 1,000 casos y solo cuatro muertes.

A fines de febrero, Corea del Sur parecía estar en una trayectoria hacia el desastre, con el mayor número de casos confirmados fuera de China, y los números aumentaron rápidamente. Pero después de la primera infección del país, el gobierno se reunió con compañías médicas y les instó a comenzar a desarrollar kits de prueba de coronavirus a gran escala.

Los resultados fueron impresionantes. When the epidemic hit, it was ready to deploy largescale testing. Its measures allowed South Korea to become the second country to flatten its coronavirus curve, without the sweeping shutdowns of society and economic activity that China had pioneered and the west would be forced to adopt.

China’s experience should have provided a grim template for western countries to use to prepare. The speed with which Wuhan’s crisis had intensified showed that a relatively advanced medical system could be swamped. Within three weeks there were over 64,000 people infected and 1,000 dead.

The pleas for help from Wuhan’s residents and doctors were to be echoed by those from Italy a few weeks later, and soon after the UK.

Look back three months, and in China there were not enough tests to work out who had coronavirus, there was not enough protective equipment for medical staff treating patients, and then, soon, tragically there were not enough hospital beds and ventilators for sick patients. These are exactly the challenges faced by authorities from New York to Rome, London to Madrid.

… and the other country that didn’t listen

If the UK has serious questions to answer, the country that so far has seen the worst of the outbreak, the United States, was slowest of all to act. Trump for months ignored, played down or lied about the threat posed by coronavirus, leaving individual states to act unilaterally as it became clear it had already taken hold on US soil.

On 17 March parts of California issued “shelter in place” orders, effectively a lockdown. By the end of that week New York City had also shut down, along with a dozen states, and the majority of the rest of the country had put some restrictions in place. Only five states had few or no controls.

There have now been nearly 700,000 confirmed cases in the US and over 33,000 deaths; actual numbers are likely to be higher for both. The economy has also been devastated, with more than 22 million out of work as businesses collapse or shrink under the strain.

Trump insists the US is turning a corner, and has tried to blame – among other targets – the WHO for failing to fully raise the alarm, and has stripped it of its US funding.

There have certainly been questions about the organisation’s strong praise for China and the exclusion of Taiwan, which may have contributed to the delay in recognising human-to-human transmission was occurring. But it began daily briefings on 22 January and had declared a global health emergency by the end of that month.

While initially sceptical about China’s distancing measures, it urged other countries to adopt them once there was evidence they were working. It warned about shortages of PPE over a month ago, and since the beginning of the outbreak has urged countries, including the UK, to “test, test, test” to contain the virus – a strategy followed by almost all countries that have managed to suppress it.

A senior Whitehall source with detailed knowledge of the UK’s response and those of other countries said: “The fact is that those countries who knew a lot about Sars quickly saw the danger. But in the UK the attitude among politicians and also scientists was that it was really just some form of a flu. All the government’s pandemic planning was based on a flu scenario. And then it turned out to be something different and far, far worse and the response was completely inadequate.”

And we are going to be living with the consequences for a long time. Don’t expect a vaccine to come to the rescue in the short term, says Nabarro. “For the foreseeable future, we are going to have to find ways to go about our lives with this virus as a constant threat to our lives. That means isolating those who show signs of the disease and also their contacts. Older people will have to be protected. That is going to be the new normal for us all.”

[ad_2]