[ad_1]

-

Immigrant crisis in Europe

The European Union has called for a mandatory bloc-wide system to manage migration, after years of division over how to respond to a large influx of migrants and refugees.

The German-backed pact would require the participation of all 27 EU countries.

Member states would agree to take in asylum seekers or undertake to return those who are denied asylum.

The head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, called it a “European solution … to restore the trust of citizens.”

The recent fires that destroyed Greece’s Moria camp, which is home to more than 12,500 migrants and refugees, were “a stark reminder that we must find sustainable solutions,” he added.

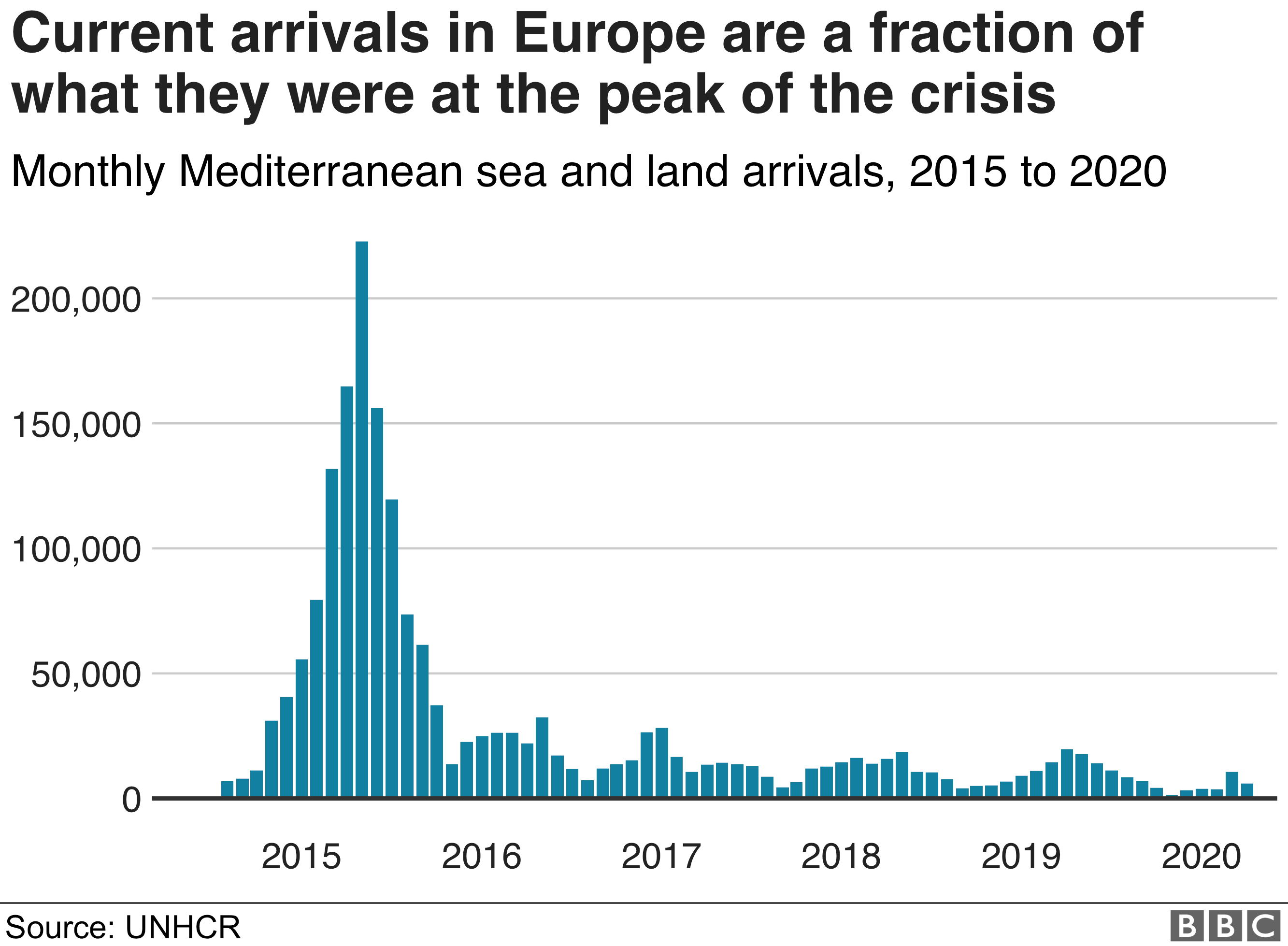

Since the influx of more than a million migrants and refugees in 2015, mainly through Italy and Greece, the 27 EU states have been divided on how to respond, and the new pact has already drawn criticism.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz questioned the idea of distributing asylum seekers in Europe. “It won’t work like that,” he told the AFP news agency.

Italy and Greece have accused the richest countries in the north of not doing enough, but several Central and Eastern European nations have openly resisted the idea of accepting a migrant quota.

What’s in the plan?

The new pact, which has been pushed harder by German Chancellor Angela Merkel, proposes a “fair sharing of responsibility and solidarity among member states while providing certainty to individual applicants.” There would be:

- New mandatory pre-entry control that includes health, identity and security controls

- A faster border asylum process involving quick returns for unsuccessful applicants

All 27 EU countries would have “flexible options” on how to participate, so countries like Hungary and Poland that have refused to accept arrivals in the past will be asked to help in different ways.

- Welcoming the newcomers

- “Sponsor” returns: ensuring, on behalf of other states, that people who were denied asylum are returned

- Provide immediate operational support

The president of the European Commission said that the new pact “will rebuild trust among member states” and achieve the “proper balance between solidarity and responsibility.”

Previous reports suggested that each member state would host a number of refugees in exchange for about € 10,000 (£ 9,200; $ 11,750) per adult and € 12,000 for an unaccompanied child. Those who do not comply with the pact could face legal proceedings and hefty fines.

There is no easy solution to a long-term crisis

Analysis by Kevin Connolly, Europe correspondent

image copyrightfake images

Of all the problems that have plagued the European Union, none is more chronic or more corrosive than migration. The search for solutions began even before the upheaval of 2015 saw the arrival of a million migrants, refugees and asylum seekers to the shores of the bloc.

And the 2016 deal under which Turkey agreed to withhold some of that tide of humanity in exchange for substantial cash payments now shows signs of strain. That leaves the EU countries where immigrants first land, especially Greece and Italy, with most of the burden.

But Poland and Hungary have resolutely resisted plans for mandatory sharing in the past. The EU’s money or plans for faster processing of asylum applications are unlikely to change their views.

For this reason, when the EU Commissioner for Internal Affairs, Ylva Johansson, says that “no one will be satisfied” with these new measures, she is highlighting the compromise that must be reached between humanitarian duty and political reality.

Furthermore, it also emphasizes the difficulty of solving this long-term crisis.

Because right now?

The new pact, which has been pushed more strongly by German Chancellor Angela Merkel, has been advanced after the fires in the Moria camp on the island of Lesbos.

-

How the immigrant crisis changed Europe

- Hundreds of migrants continue to die in the Mediterranean

- ‘Europe does not exist. This is hell’

However, the schemes have already prompted the Save the Children charity to accuse the EU of not having learned “from its recent mistakes”.

Faster returns are also envisaged for migrants whose asylum claims have been rejected, with increased assistance for non-EU countries affected by migration.

Save the Children’s Anita Bay Bundegaard said the special childcare plans were welcome, but the charity feared the new plans “run the risk of repeating the same flawed approach” that sparked the Moria fire and previous disasters.