[ad_1]

Image copyright

Image copyright

MOD / PA

The government has reached its testing target, providing more than 120,000 tests for coronaviruses in one day in late April.

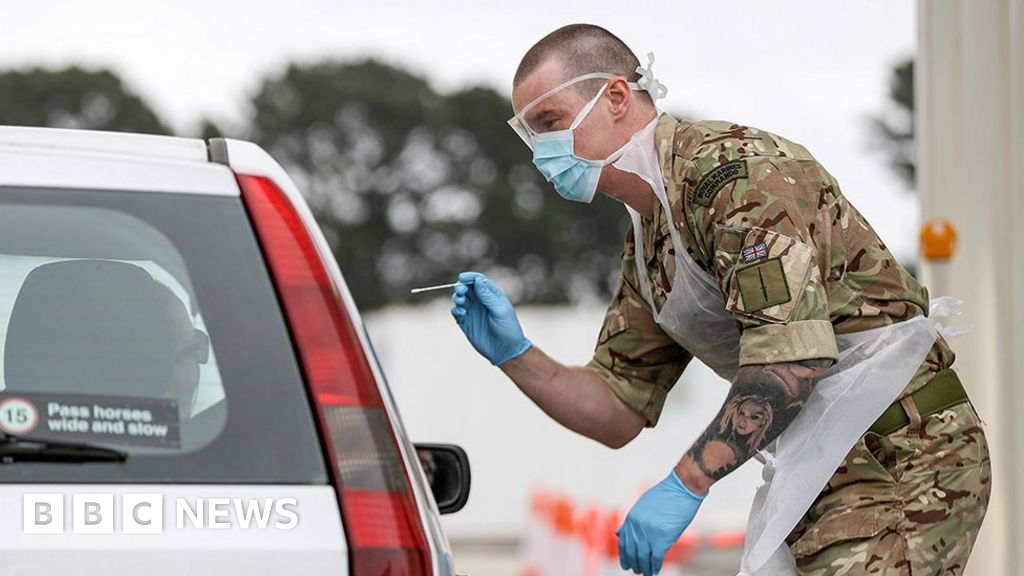

A Herculean effort was needed: three mega labs to process the tests, an online booking portal, a network of driving test centers, a home testing service, and the army deployed to run 70 mobile test units.

The government has been accused of being somewhat creative with its count by including home test kits shipped to individuals and lots delivered to care homes, but not yet returned. Some of them may never be completed.

But even if I had to discount them, the government has still made an eight-fold increase from where we were a month ago. It is certainly an impressive feat.

However, there are still serious questions to ask about the government’s approach to testing.

Was the government slow to react?

In the early days of the pandemic, the government quickly boasted of its ability to test. The ability to perform 1,000 tests was quickly increased to 3,000.

But as the outbreak spread, it quickly became apparent that the testing system was going to be overwhelmed.

Public health England and health officials in the rest of the UK relied on eight small laboratories and their own evaluators.

That policy was in place for weeks before the government entered into serious talks with hospitals, universities and the private sector to increase testing capacity.

Media playback is not supported on your device

Should it have been done before? Many think so.

Part of the problem was that the official approach until mid-March was to let the virus spread in a controlled way.

That meant that there was little incentive to expand the tests far beyond hospital patients.

With local outbreaks, the reasoning behind the World Health Organization’s “test, test, test” mantra did not seem like a priority.

Has the lack of evidence to date cost lives?

Many believe that the delay has been costly. If more evidence had been available for nursing homes, for example, more lives could have been saved.

Media playback is not supported on your device

Until mid-April, testing was stopped once a care home passed five positive cases. And staff who showed no symptoms were unable to be tested until the end of April despite concerns that care workers were unknowingly causing outbreaks because they were infected but showed no symptoms or transmitted the virus before becoming ill.

When asked recently in a daily briefing if that had cost lives, he said that Foreign Minister Dominic Raab could only say that the lessons would be learned.

Professor Devi Sridhar, President of Global Public Health at the University of Edinburgh, believes that the UK and others in Europe, as well as the US In the US, they were “accommodating” about the destruction that infectious disease outbreaks could cause, having escaped the major Sars outbreaks. , Mers and Ebola.

Did the 100,000 goal help or hinder?

Chris Hopson of NHS Providers, who represents healthcare leaders, believes the goal has certainly had a “galvanizing” effect.

But he says the obsession with the 100,000 figure could be a “false lead” and could instead have led to “testing for the sake of proof.”

Remarkably, in the past week, eligibility for testing has expanded rapidly from hospital patients, nursing home residents, and key personnel to everyone over 65 and anyone who needs to leave home to work in England.

And yet, nursing homes still say they are fighting to have staff and residents screened, and NHS staff have reported that they cannot reserve tests because the spaces have already been taken.

Meanwhile, the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, which represents laboratory staff, has questioned the use of unregulated volunteers to perform swab tests; if not performed correctly, it may affect the accuracy of the test.

How do we compare internationally?

Professor Allyson Pollock, a public health expert at Newcastle University, says the effort has been undermined by the “huge” lack of public health funding in recent years.

Certainly, the UK has had to run to catch up.

South Korea, which has managed to contain the virus to the point that it reported Thursday that it had seen no new domestic infections, had more than 200 labs ready to test from the start.

He certainly benefited from his experience in fighting the Mers and Sars outbreaks in the past two decades.

Germany, another country to which the United Kingdom often compares unfavorably, also had a built-in advantage in that it had a well-established biomedical engineering industry, which meant that it was not as affected by the global paucity of testing for chemicals and kits that other countries were.

But there are many other countries, from Italy to Lithuania, that have consistently outpaced the UK.

Professor Pollock also believes that there has been a “lack of consistency” in the approach taken for testing without a general strategy to shore it up.

In particular, it is concerned that the United Kingdom may be ill-prepared for the next phase of the fight against coronavirus.

The biggest test to try is yet to come

The ultimate goal will be to provide evidence to anyone in need throughout the population so that local outbreaks can be contained once the blocking restrictions begin to ease.

But for containment to work, you’ll need the tests to turn around quickly, it can still take 72 hours from start to finish for some, and then a quick and effective way to track down people with whom infected people have been in close contact. .

The government points to the developing contact tracking app and the “army” of 18,000 trackers being recruited. But it is not yet clear how they will unite with the test system.

Local authorities, where many of these contact trackers are expected to be obtained, have already expressed frustration at not being properly involved.

If the test and trace regimen is ineffective, any relief from the crash is bound to fail.

The 100,000 test target may have passed, but the biggest challenge is yet to come.