[ad_1]

“I just felt like it was the right time to speak. I had carried the burden of not speaking for nine years.”

Anton Ferdinand was scared. Bullets in the post, missiles launched at his mother’s house, fears for his career as a soccer player.

But he is no longer afraid.

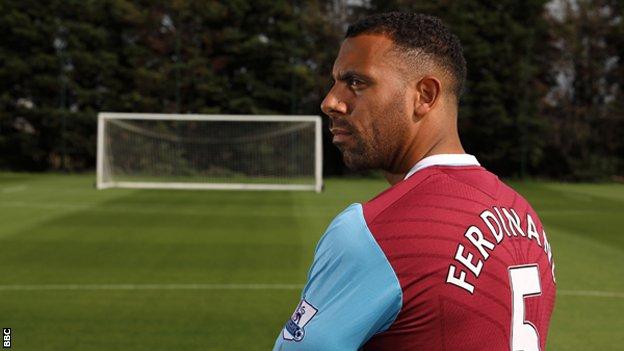

In Anton Ferdinand: Football, Racism And Me, a new film set to air on BBC One on Monday 30 November, the retired footballer discusses the repercussions of being at the center of a storm of racism in the Premier League nearly a decade ago.

It ended when the Football Association found John Terry guilty of using racially abusive language towards Ferdinand during a game. Terry was fined £ 220,000 and banned for four games by the FA and later he lost the captaincy of England. A court of law had previously found him not guilty.

The case dominated English football for months. It left Ferdinand traumatized, feeling that he had not been supported by the gambling authorities and with a persistent sense of guilt for not speaking publicly about it.

But, in his own words, he has regained his voice and speaks passionately about what his film “for the next generation” is like.

What happened between Ferdinand and Terry?

In a powerful scene early in the film, Ferdinand, now 35, remembers the day of the incident.

In October 2011, he was involved in an on-court dispute with Terry, whose Chelsea team had two men sent off in a 1-0 defeat against Ferdinand’s Queens Park Rangers.

Television cameras caught Terry appearing to use racially abusive language as he walked away from an argument, in which Ferdinand acknowledged that he had used abusive language towards Terry.

In the movie, Ferdinand explains that he didn’t hear Terry say the words. He describes how the pair shook hands after the game, saying they agreed to dismiss his argument as “just a joke.”

Ferdinand says the first thing he knew about the use of racist language was when he met his family in his box on Loftus Road.

“I was excited, we just beat Chelsea,” he says.

Ferdinand’s wife later handed him a phone to show him pictures of the incident.

“I’m looking at the phone and anger washed over me,” he says. “You know when your blood boils, it just hits me. I wanted to go hurt him.”

But Ferdinand says his mother prevented him from immediately challenging Terry.

“She was the only person who could have stopped me,” he says. “She said, ‘I know what you want to do, but now is not the time.’

‘I punished myself for not talking’: what happened next

After a member of the public complained to the police, it was announced in December 2011 that Terry would face a criminal charge for using racist language.

Terry, who swore to clear his name, was stripped of the captaincy of England, prompting National chief Fabio Capello will resign.

Terry’s defense was that he was repeating language that he thought Ferdinand had used, and he was not using it as an insult.

In July 2012, Terry was cleared of racism by a court of law. The judge said: “The evidence from the prosecution on what Mr. Ferdinand said at this time is not solid. Therefore, it is possible that what [Mr Terry] He said it was not an insult, but a challenge to what he believed he had been told. “

Two months later, the AF came to a different conclusion and found terry guilty of using racially abusive language.

Ferdinand, who says in the film that he did not want the incident to go to court, was silent.

In one scene, he almost breaks down in tears when he reads a comment from the anti-racist charity Kick It Out, which criticized him for not making a public statement.

“I punished myself for not speaking,” he says.

But his older brother Rio, a former England defender, says Anton was advised to keep quiet.

The former Manchester United central defender says: “Apart from a few close friends and family, especially Mom and Dad, everyone else was saying, ‘Don’t say anything, let the lawyers deal with it.’

‘They sent me bullets in the mail’

As Ferdinand remained silent, he continued to receive abuse from the public.

He was racially abused so much on social media that he says he came to “expect” him every time he looked at his phone.

“It was every hour,” he says. “My mother’s house was hit with missiles. They sent me bullets in the mail.”

Ferdinand now acknowledges that he was traumatized, but at the time he just wanted to focus on football.

That, however, was difficult.

Neil Warnock, QPR manager at the time, says the defender was not the same player after the incident.

“That was very, very difficult to hear,” says Ferdinand. “However, it was something I needed to hear.

“I’m not ashamed to say it now, I was scared. If I had talked about it at a certain point, it could have been the end of my career.”

“When it happened, I think I was in more than 200 Premier League games. I think I played 10 more after the incident, and that was my destiny. I had to go play in Turkey. I came back and went down the leagues.”

After leaving QPR in August 2013 to join Turkish Antalyaspor and then moving to Thailand, Ferdinand returned to the UK in 2014 to play for Reading. They followed spells in Southend and then St Mirren in Scotland before retiring in July 2019.

Ferdinand says that staying silent went against one of the core values that his mother had instilled in him: speaking out against injustice.

“My mother was a white woman who fell in love with a black man,” she says. “My mother endured racism: people spat on her, they spat on us in the stroller. She went through that because she loved her children.”

And Ferdinand says he didn’t speak anymore because he had faith in the soccer authorities.

“I left it to the powers that be,” he says. Looking back, you don’t feel like things have been dealt with correctly.

In the film, he and Warnock describe how they felt that, during conversations with the FA, Ferdinand was treated as if he were a suspect, rather than a victim.

“They were investigating me, as if I had done something wrong,” says Ferdinand.

In another scene, he hears a recording of part of an interview between Terry and the FA.

“Hearing that confirms to me that they treated me differently,” he says.

The FA says it challenged Terry, but was unable to provide the full interview at the time. A recording of Ferdinand’s interview was not kept.

He hopes the documentary shows that “the organizations that should have been there weren’t there to support me,” adding: “I never got a phone call to ask how I was doing. I should have knocked on the door.”

And he believes there needs to be more authority figures with a real understanding of these kinds of issues.

“The decision makers, at the top, will never really understand what it feels like to be involved in an incident like me because it wouldn’t happen to them,” he says.

“What they can do is try to understand by talking to and working with people who have been involved.”

He is also hurt by the criticism he received from Kick It Out, which he says “shows how lonely he was.”

In one scene, we see him meet psychotherapist Dee Albert, who works with people who have been abused.

“I still have that feeling of disappointing people,” he tells her. “That corrodes me more than anything.”

Albert explains to Ferdinand that silence is a typical response to abuse.

“I can definitely relate to that and that helped me because I didn’t feel like I was alone,” he says.

‘This is bigger than Anton v John’

Ferdinand credits Watford defender Renee Hector with being able to see things differently now.

In 2019, an independent FA regulatory commission discovered that Hector, who was then playing for Tottenham, was racially abused by Sheffield United’s Sophie Jones during a Women’s Championship match.

Héctor reported the incident and spoke publicly about it on social media.

Ferdinand speaks of his admiration for her, and the feeling is mutual.

“I don’t think you realize how important what you are doing now will be,” he tells her in the movie.

“Renee allowed me to understand that life is a matter of time and my time is now to speak,” says Ferdinand. “There is no right or wrong way to do it.”

Ferdinand also tried to contact Terry for the movie; They haven’t spoken since that day on Loftus Road, though Terry tried to reach Ferdinand afterward. Terry did not respond to Ferdinand’s message, but his representatives did respond to the production team, saying that he has moved on with his life and does not want to reopen a television case that was decided in court.

Ferdinand told BBC Sport that he tried to contact Terry because “my message is clear, he is bigger than him and me.”

“This is the next generation,” he says. “I feel like if we got together and talked about our journey, it would help the next generation and also the powers that be within football.”

“I would never have made this documentary if it was just about John and me, or if it was an Anton v John documentary.”

Part of Ferdinand’s process has been sharing his story with young players who might go through similar things, and letting them know that he is available to support them.

“If I have to drive to Carlisle to knock on a player’s door and ask how he’s doing, I’ll do it,” says Ferdinand. “I don’t want anyone to feel like I did nine years ago.”

For now, he’s happy to be in control.

“I have my voice back,” he says. “And I’m using it in the right way.”

Anton Ferdinand: Football Racism and Me, arrives on BBC One on Monday, November 30.