[ad_1]

Tectonic activity has been detected on the moon by researchers who discovered a system of mobile, rock-capped ridges on its near side.

“There is an assumption that the moon is long dead, but we continue to discover that this is not the case,” said Professor Peter Schultz of Brown University in Rhode Island.

“It appears that the moon may still be cracking and cracking, potentially today, and we can see the evidence on these ridges,” explained Professor Schultz, co-author of a study published in the journal Geology.

Most of the moon’s surface is covered by something called regolith, the powdered rock dust created by constant meteorite impacts.

Because the moon has no atmosphere to speak, rocks and debris in orbit directly hit its surface and are destroyed.

There are very few gaps on the lunar surface that are not covered by the regolith, but some apparently new spots have recently been discovered.

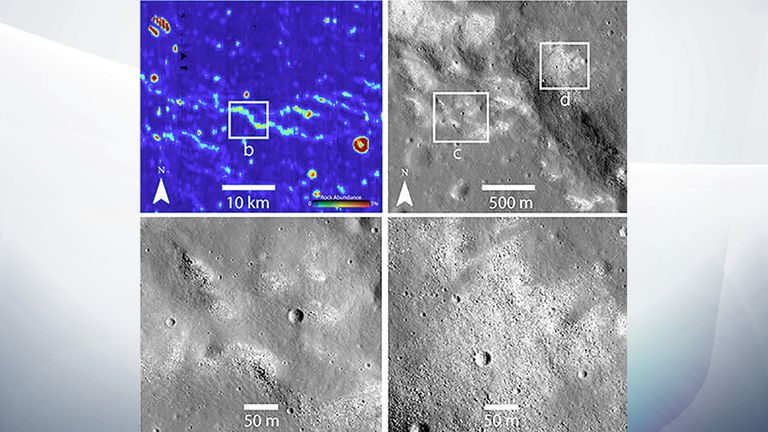

Adomas Valantinas, a graduate student at the University of Bern who was a visiting scholar at Brown, used data collected by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) to detect these strange naked spots.

“The exposed blocks on the surface have a relatively short life because regolith accumulation occurs constantly,” Schultz said.

“So when we see them, there must be some explanation of how and why they were exposed in certain places.”

“In the same way that concrete-covered cities on Earth retain more heat than the field, the bedrock and block layers on the moon remain hotter during the lunar night than regolith-covered surfaces,” the researchers said.

Then, using a tool on the LRO to measure surface temperature, Valantinas was able to discover more than 500 patches of exposed bedrock on narrow ridges by following a pattern on the near side of the moon.

Such ridges had been discovered before, but were at the edges of very old lava-filled impact basins and could be explained by the continued sagging in response to the weight caused by the lava fill.

The new study found that these ridges are actually related to a mysterious system of tectonic features (ridges and faults) unrelated to lava-filled basins.

“The distribution we find here asks for a different explanation,” said Professor Schultz.

By mapping all of these exposed ridges, Mr. Valantinas and Professor Schultz discovered an interesting correlation between them and a previous NASA mission.

In 2014, NASA’s GRAIL mission discovered a network of ancient cracks in the lunar crust, which became channels for magma from the moon’s core to flow to the surface.

This network was aligned almost perfectly with the block ridges.

“It’s almost a one-to-one correlation,” said Professor Schultz. “That makes us think that what we are seeing is a continuous process driven by things that occur inside the moon.”

So, according to these scientists, the ridges are ancient magma flows that still rise upward, breaking the surface and draining the regolith into cracks and gaps, leaving the blocks exposed.

“Because the bare spots on the moon get covered fairly quickly, this cracking must be fairly recent, possibly even current,” they say.

But what is causing this? According to scientists, tectonic movements may have started billions of years ago with a giant impact on the other side of the moon.

Professor Schultz had previously proposed that such an impact had formed the 1,500 mile South Pole Aitken Basin, and had shattered the interior on the opposite side of the moon, the side facing Earth.

Core magma then filled these cracks and controlled the pattern detected on the GRAIL mission. The blocky ridges that comprise this network now plot continuous adjustments across these old weaknesses.

“This looks like the ridges responded to something that happened 4.3 billion years ago,” said Professor Schultz. “Giant impacts have long lasting effects.

“The moon has a long memory. What we are seeing on the surface today is testimony to its long memory and secrets that it still holds.”