[ad_1]

People rejoice in unexpected favors differently than they expect. Surprise at work has a broader and more lasting effect than satisfaction in confirming expectations, increasing confidence in good prospects. The award of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Louise Glück had such an effect on me, it surprised me, it made me happy, I felt optimistic in a difficult moment.

The sexual harassment scandal that resulted in the Swedish Academy failing to award the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2018, followed by the committee’s election by Peter Handke, who awarded two awards last year: a man who used his pen and his charge to support the denial of genocide and support the genocide, while relinquishing Handke’s literary power. The author’s reward was not something that could be called “the only measure of literature”: the outrage it provoked increased his expectation that the awards committee would make a choice (and therefore a political and populist choice) that this time it cleared your name. Judging by the stakes before the award was announced, it was also possible to get the “right” political message across with a choice like Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o or Antigua Jamaica-based American writer Kincaid, a writer with millions of dollars. readers (and supporters) around the world like Haruki Murakami or Margaret Atwood. rewarding too.

Does the fact that the American Louise Glück, 77, won the 2020 Nobel Prize for Literature, frustrate these calculations, or is it that the coronation of a woman, a poet (and a good essayist, although that aspect is not emphasized what enough) is it still an accounting business in itself today? I can’t be sure.

After all, he is the second generation of a Jewish family born in the United States of Hungary, he grew up in New York, his father got rich as an inventor and patent holder of a kind of knife model, his mother graduated at Wellesley College, he studied in good schools although he did not receive a degree. (Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University), we are talking about someone who has been a writer and professor at Yale for years and of course writes in English. Seen this way, Glück stands somewhere between what the institutional order of literature “always considers” and what it “easily ignores.”

But if “the only measure is literature”; If it is to achieve an effect that expands the reader’s imagination, sharpens his perception and facilitates the struggle of life by speaking new words – or by saying the same words in another way – participating in the literary effort to understand and explain the human being and the universe with a single voice, the criterion is to celebrate the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature. We have a very good reason for me. Louise Glück has been doing this for almost sixty years because she is writing a poem that is distinctive, rock solid and tough, but with humor and music that questions, impacts, and I think is genuine.

I think the following words from the Chair of the Awards Committee, Anders Olsson, about Louise Glück have been received by those familiar with her poetry:

a sincere and uncompromising voice … a poem that strives to be clear … a poet who remembers Emily Dickinson with her violence and her reluctance to accept easy-to-believe rules.

Couldn’t say better!

Louise Glück’s poem is very simple and direct at first glance; as simple as if it spoke and consumed everything that was on the surface. But this frankness, which makes poetry attractive and easy to enter, is accompanied by layers that require the reader’s effort to penetrate deeply; The stone that you find at first glance turns into pebbles that you have to chew and swallow each one of them.

Louise Glück’s parents buried their first daughter who was born before her at a young age. Louise never knew her deceased sister and grew up with a younger sister. This death, which he did not witness, determined Glück’s poetry as much as his life.

In one of his essays, “I did not experience his death, but I did experience his absence. “I was born because he died.” The family, the deceased sister and the younger sister are at the forefront of Glück’s poems, especially in the initial period. Likewise, the anorexia he struggled with as a young man is reflected in the contact of the person Glück often turns to with hunger and his body.

But even in his obviously autobiographical poems, we find a poet who resists not falling into a “confessional” mood and style. He does not say to us, “Come, let me pour myself on you.” He doesn’t want to be cute, playful, or familiar. He does not hide that he is angry at him when he thinks he cannot escape these traps enough. Released in 1968 Firstborn (İlkdoğan) – It implies the deceased sister – of course – I read that she later regretted some of the poems in her book for exactly this reason.

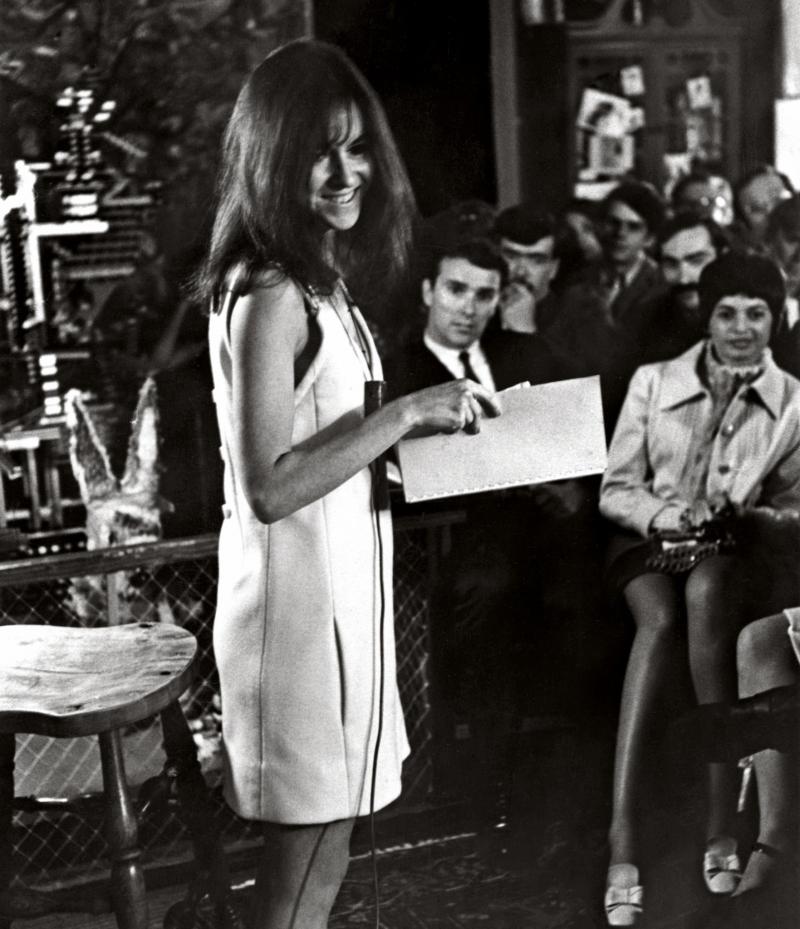

Luck, 1968.

Over the years, there have been those who criticize Glück for not lowering his guard, for not undressing enough in front of the reader, with extreme control over the years, perhaps for the temperance that this effort to “escape from. the traps “puts in their language. However, despite the multifaceted, harsh and dense nature of his poetry and this criticism of “detachment, restraint”, Glück is a favorite poet in his country and has a wide audience. Use the knowledge of the mythology of classical education by transforming parables and using myths in their poetry; the agility to speak with voices of gods, flowers, mountains, men and animals; I think its mischievous aspects, which can take life or death, domestic situations, and marital situations, make it easier to attract different readers.

With Ben Glück’s poem, in his senior year 1984, Firstborn Glück was a poet who had entered American schools as a “lesson” at the time. The books he published in the years that followed always resonated. Among many other awards, Achilles triumph (Victoria de Aquiles – 1985) and the National Prize for Book Critics; my favorite book The Wild Iris (Wild Iris – 1993) with the Pulitzer Prize Winner and William Carlos Williams; and more recently Faithful and virtuous night He won the National Book Award with (Sadık ve Erdemli Night – 2014).

Glück also served as a “Poet Laureate” (a kind of poet-i âzam) in the United States between 2003 and 2004 and received the National Medal of Humanities from President Obama in 2015. In short, he is a poet at the center of the canon of the American verse. However, his poetry is not widely known outside of European languages. We were lucky in spite of everything in Turkey, Yapı Kredi Publications, 1994, a selection is made from until then all the books published by the Turkish Turan Trust had been published. Undoubtedly, new books and new translations will be produced on the occasion of this award.

At the end, I leave a link to a video that I think would be a nice meeting for those who speak English but have never read Glück. And I want to end with a poem that, I think, reflects Louise Glück’s poem well, expressing her courage and concern.

Unreliable speaker

Do not hear me; my heart is broken.

I don’t look at anything neutrally.

I know myself. I learned to listen like a psychiatrist.

When I speak passionately

especially back then, I’m not trustworthy.

Very sad truth: all my life I have been praised

out of my intelligence, out of my power to use language, out of my perception.

In the end, all in vain

I can never visualize myself

while holding my sister’s hand on the steps in front of the house.

I can’t account for this either

the bruises on his sleeve where his shirt ends.

I am invisible in my own mind; I am also dangerous for that.

People like me who always seem to think of others

we are the crippled, we are the liars;

we are the sacrifices

for the sake of truth.

The truth becomes clear when I remain silent.

Clear sky, clouds like white fiber.

Below, a gray house, azaleas

bright red and pink.

If you want the truth you have to close

For your oldest daughter, you should leave her out:

a living being like this,

when it hurts to the core

its role is completely changing.

That’s why I can’t be trusted at work.

Because a wound in the heart

it also opens in the mind.

(Translated by: Yasemin Çongar / Poem in English here.)

•