(Bloomberg Opinion) – As the coronavirus pandemic continues, Bloomberg’s Opinion will execute a number of characteristics from our columnists who consider the long-term consequences of the crisis. This column is part of a package on the future of transportation.

Last month, my wife and I planned our first vacation in six months. It was a hectic experience. The borders between most Australian states had been closed since the onset of the coronavirus blockade. We had hoped to fly three hours to the tropical resort town of Cairns, in the northeast state of Queensland, to escape the winter and Sydney holidays with friends.

Within hours of the announcement that the Queensland border would be opened, tickets on the handful of northbound flights began to run out. With so few seats available, performance management, the practice by which airlines monitor minute-by-minute demand for their seats and increase prices accordingly, was underway. By the time we finally booked, we had spent around A $ 1,000, or 40%, more than if we had been faster.

That’s a vision of what awaits travelers as the world emerges from Covid-induced hibernation in the next two years. Global air traffic is projected to decrease by at least half in 2020. Most airlines believe that companies will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2023, at the earliest. Even then, it will still feel like a slump for an industry that had hoped to be up to a fifth larger at the time.

The financial consequences for large carriers and their employees will be heartbreaking, and passengers who start flying again will have to bear the costs. Prolonged recovery will accentuate all aspects of the flight that travelers regret. Did you think traveling in 2019 was expensive, crowded, mean and lacking in glamor? Get used to it.

***

The decline in business travel poses the greatest threat to the industry. Premium class travelers account for about 5% of traffic, but 30% of airline revenue, allowing operators to offer budget seats at cheaper prices. Tight corporate budgets and the rise of video conferencing under lockdown may have killed a sizable chunk of that industry. About 60% of travel managers surveyed by BCD Travel in April expect the frequency of business travel to be lower even after the pandemic subsides.

Of all the affordable and premium-class tickets purchased by companies, “10% -15% will never return,” Ben Baldanza, former CEO of budget airline Spirit Airlines Inc., said by email. “The video was available before Covid, but now companies have experience and confidence in using it.”

Recessions generally lead to a three-year drop in air travel, and the one we’re seeing is likely unprecedented in depth and length. According to Baldanza, long-distance operations could still struggle in five years. The first days of recovery can bring bargains as carriers try to convince passengers to get back on board, although we certainly didn’t get one for our vacation. However, sooner or later, the industry will have to reckon with the mountain of debt it took on.

There is simply no flight map for this. Companies with net debts of more than four or five times the size of their Ebitda are conventionally considered to be at high risk of non-payment. That proportion will reach 16 for the airline industry globally in 2021, according to the International Air Transport Association. Those levels are rarely seen in companies outside of the financial and real estate sector, unless they are on the verge of bankruptcy. For an entire industry, it is unheard of.

Some operators will be able to withstand the crisis better than others. Those with strong positions in the large domestic markets that have rid themselves of the worst of the virus, such as Australia, Japan and China, should do better, as do regional Asian airlines and low-budget airlines in the European Union. Due to their low-cost foundations, short-range discount operators are likely to be more resilient than their full-service rivals.

Airlines based in the large domestic markets most affected by Covid-19 (US, India, Brazil, Russia) will find things more difficult. The most affected are likely the handful of airlines that spent the past two decades aspiring to connect the world as global airlines. The type of long-distance connecting traffic that Singapore Airlines Ltd., Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd., Emirates, Etihad Airways PJSC and Qatar Airways QCSC specialize in will not be seen as a viable business for many years.

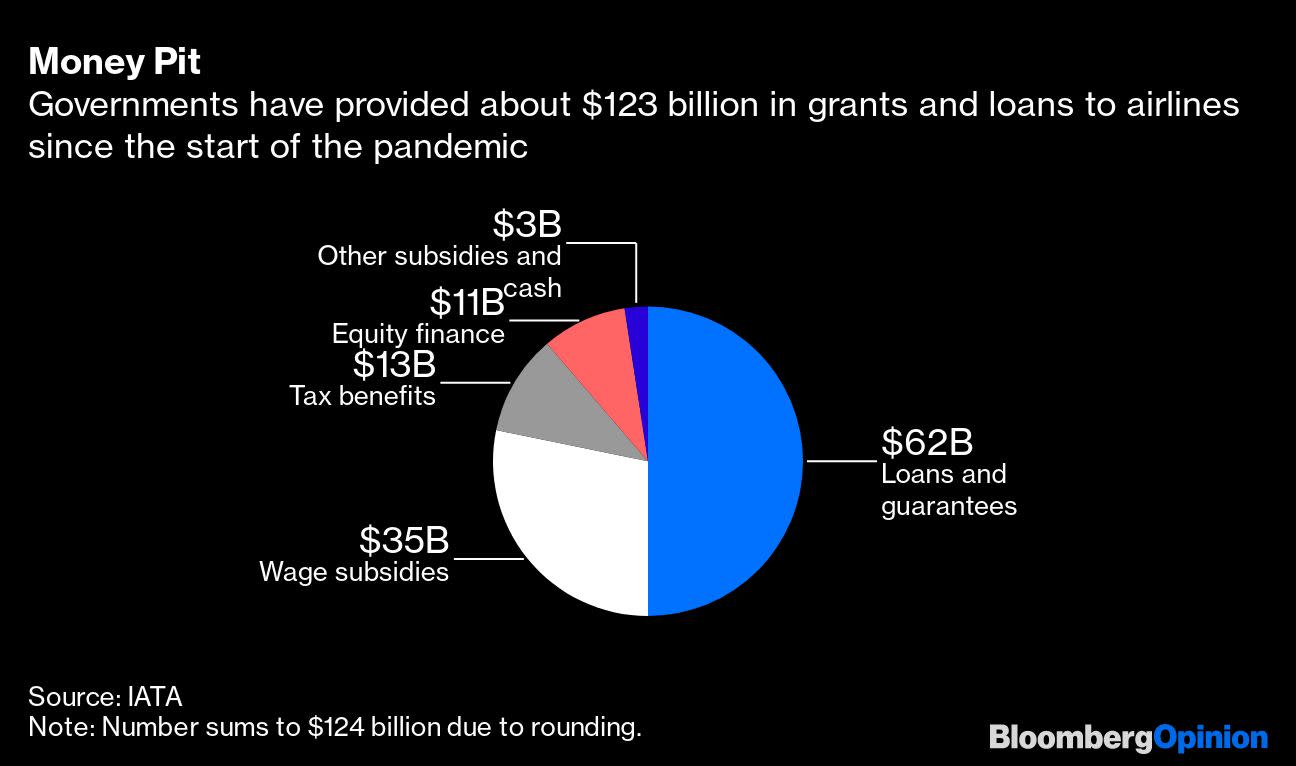

Fortunately for its employees and passengers, everyone except Cathay has controlling state shareholders who see flagged airlines as critical to their economic future. The role of the state will be impossible to escape in the next decade. Governments have already awarded about $ 123 billion in aid, equivalent to the last four years of industry profits. The damage the coronavirus is causing to traffic and the centrality of quarantine measures mean that only a handful of mainly low-cost carriers are likely to survive on their own. Lufthansa AG is likely to pay off debts instead of buying new aircraft in the coming years, Bloomberg News reported last week, while IAG SA’s British Airways will withdraw its 747 fleet. Many airlines will need continued state support in addition to the bailouts. have already taken place.

In any case, the future of those companies looks bleak. Operators who do not receive government backing will go bankrupt. Those who receive aid still risk ending up in the position of state-owned sclerotic flag bearers like Alitalia SpA, Malaysia Airline System Bhd. And Air India Ltd., shaking from crisis to crisis under the weight of government loans.

***

That will translate into unpleasant experiences for passengers. You are unlikely to find yourself surrounded by empty socially distant seats, including easyJet Plc, which proposed that move in April, later ruled it out. Airlines at best cannot make money unless they fill 80% of the plane. On the first leg of my flight from Sydney to Brisbane, each of the 174 seats on board was occupied, and the second leg from Brisbane to Cairns was 90% full. Your best hope of avoiding infection will be to wear a mask, rely on the reliability of cabin air filtration, or avoid flying entirely.

Carriers will also amplify the existing trend toward making money where passengers seem insensitive to price; in other words, everything but the tickets themselves. Supplemental revenue from things like baggage fees, extra legroom, on-board dining, frequent flyer points, and hotel and car rental bookings has grown fivefold in the past decade to reach $ 109.5 billion a year Last, according to IdeaWorksCompany consultants. That is more than 12% of general airline revenue and in some discount companies it represents up to a third of the total. The aftermath of the pandemic will provide carriers with a reason to stop distributing free food and drinks that could carry an infection. They will come tied with a rigid price in the future.

Baggage fees will also skyrocket. The brightest point in the aviation industry right now is cargo. Due to a shortage of passenger flights, cargo holds are more crowded than ever, allowing carriers to raise prices. Baggage fees are a way to earn additional revenue in the passenger cabin and discourage people from bringing suitcases, freeing up more space under covers for profitable commercial shipments.

As for seats, passenger groups believe that a review of seat sizes to be launched this summer by the US Federal Aviation Administration will give carriers the green light to bring people even closer. In a typical Airbus SE A320 or Boeing Co. 737, every inch that takes off from legroom could open up room for an additional row of passengers, up to the maximum levels determined by evacuation protocols. Seat designers these days offer products with just 28 inches between each row, compared to levels from 31 inches to 33 inches at most full-service operators. Those who are too tall to crawl into such spaces may find that paying an additional fee for decent legroom is the only way to stretch.

The truth is, consumers are willing to overlook all sorts of indignities in the name of cheap fares, as evidenced by the success of merry and spartan airlines like Ryanair Holdings Plc. However, everything is relative in the price of the tickets; In the post-pandemic era of flying, tickets can only seem cheap. Surviving carriers will have more market power thanks to the collapse or takeover of their rivals, putting them in a good position to squeeze the highest rates they will need to pay off their debts. Witness the recent history of the U.S. aviation industry, when nearly 200 bankruptcies in three decades left the sector so concentrated that even a longtime skeptic like Warren Buffett saw fit to take equity stakes, while Customer complaints soared.

Will regulators come to the rescue of consumers by avoiding further consolidation? Don’t count on it. But that generosity that governments are giving away shouldn’t be free, either. In particular, they should use their newfound influence to pressure carriers to do more to reduce emissions, one of the fastest growing areas for climate pollution. Almost three-quarters of the world’s air traffic land in North America, the European Union, or China. Given that concentration, it is only political will that prevents governments from imposing a global price on carbon emissions, something that in any case would happen to ticket surcharges in the same way that the expensive jet fuel was in the beginning. from 2010.

Two types of airline business are likely to thrive in the next decade: low-budget airlines like Ryanair and Southwest Airlines Co., and government-controlled national long-distance champions like Emirates and Singapore Airlines Ltd. For most of us, That means a future with fewer spoiled intercontinental flights on the top deck of a jumbo jet, and more tight time in cramped seats eating dry snacks and drinking $ 10 beer cans. The industry emerging from the coronavirus will be nasty, brutal, and short-lived. distance.

(Updates to Lufthansa and British Airways plans in paragraph 11. An earlier version of this column was corrected in paragraph 13 to clarify the occupancy of flights between Sydney and Cairns).

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist who covers products as well as consumer and industrial companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, and The Guardian.

For more articles like this, visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted source of business news.

© 2020 Bloomberg LP