It’s no secret that in this decade, NASA and other space agencies will take us back to the moon (to stay, this time!) The key to this project is developing the infrastructure needed to support a sustainable program of crew research and exploration. The commercial space sector also hopes to create lunar tourism and lunar mining, and sell some of the moon’s vast resources in the open market.

Ah, but there’s a snag! According to an international team of scientists led by Harvard and the Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CFA), there may not be enough resources to orbit the moon. Without some clear international policies and agreements, to determine who can claim what and where, the moon can quickly overcrowd, overload and snatch away its resources.

The team included Martin Elvis, a CFA astronomer who led the study, as well as Alana Krolikowski (University of Missouri University of Science and Technology) and Tony Milligan (King’s College College London). Paper that describes their findings recently Philosophical dealings of the Royal Society a “Focused Lunar Resources: Proximity to Rule and Justice.” Title.

Such as Dr. Elvis is a C.F.A. As explained in a press release, he and his colleagues were inspired by what they see as general assumptions about lunar exploration:

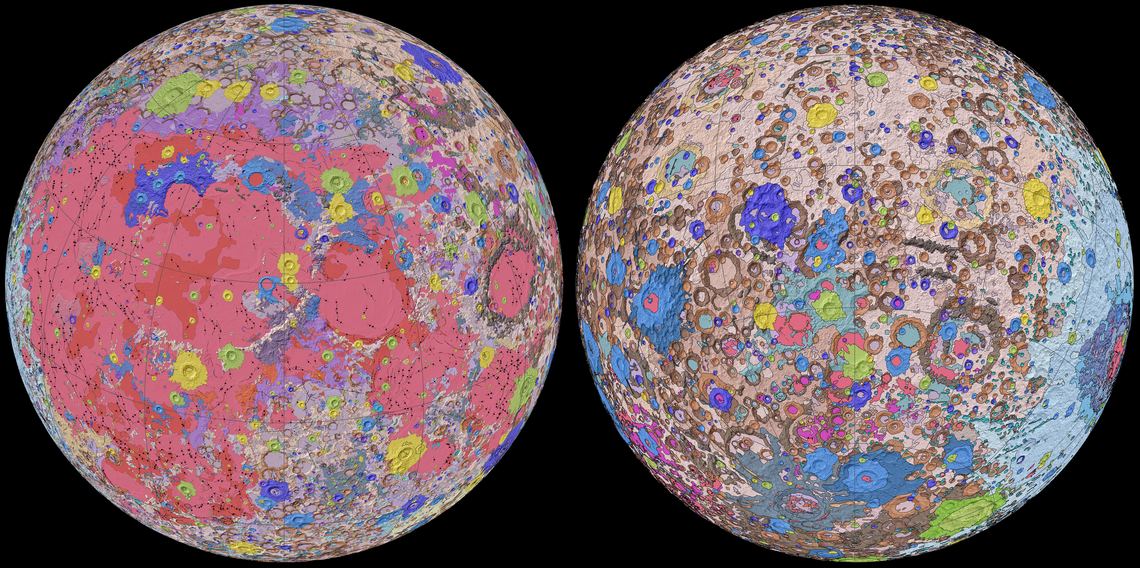

“Many people think of space as a place for peace and harmony between nations. The problem is that there are no laws to control who uses the resources, and there are a significant number of space agencies and others in the private sector that aim to land on the moon in the next five years. We looked at all the lunar maps we could find and saw that not many places had sources of interest, and those that were too small. Which creates a lot of scope for contradiction on certain resources. “

Currently, there are already treaties to run activities in space. For example, the Outer Space Treaty was signed in 1967 by the US, the Soviet Union and the UK and has since been ratified by a total of 110 countries. In addition to prohibiting the testing and deployment of nuclear weapons in space, the treaty prohibits nations from claiming supremacy over celestial bodies.

Then there are the more recent Artemis Accords, confirming participants ’commitment to coordinating and notifying each other in their activities on the moon. However, neither the outer space treaty nor the Artemis Accords prevent private companies or individuals from disclosing ownership of celestial objects, leaving the door open for things like planet potential and mining, and lunar mining.

Currently, discussions are focused on the rules of scientific versus commercial activities on the moon and who can get resources from where. Much of this is due to the fact that space agencies and commercial interests expect to harvest resources locally – in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) – to meet their needs cost-effectively. As Elvis explained:

“You don’t want to bring resources from Earth to support missions, you have to get them from the moon. If you want to make anything on the moon, iron is important; Transporting iron to the moon would be absurdly expensive. You need water to survive; You need to grow food for it – you will not bring your salad with you from the earth you will breathe for oxygen and fuel and split into oxygen for hydrogen. “

Concerns about interest and appropriation in lunar resources are all the way up to the early days of the space race. During the Apollo era, extensive research was undertaken to discover the availability of resources such as water, iron and helium. Recently, research has focused on solar power radiation in permanent shaded areas on the moon, the accumulation of water ice, and the constant on access of potentially volatile compounds.

Interest in the moon as a resource location is not new. An extensive body of research affiliated with the Apollo program has explored the availability of resources such as helium, water, and iron, with recent research focusing on solar power, cold traps, and continuous access to stagnant water storage, even on unstable lunar surfaces Exists in shaded areas.

According to Milligan, a senior researcher with the Cosmological Visionary Project at King’s College London, the question of resources may not address the real problem. “The biggest problem is that everyone is targeting the same sites and resources: states, private companies, everyone,” he said. “But those are limited sites and resources. We have no other moon to move forward. This is all we have to work with. ”

The risks are also that these sites and their resources are more limited than currently thought. For this reason, scientists are eager to return to the moon to get a clear picture of the availability of the source, before anyone can expect anything and start a ract. Elvis said:

“We need to go back and map the resource hotspots in better resolution. Right now, we only have a few miles at best. If the resources are all contained in a small area, the problem will only get worse. If we can map the smallest spaces, it will inform policy making, allow information to be shared and help everyone to play nicely so we can avoid conflict. “

Right now, the main challenge for policy makers will be to stake the resources on each individual site and it is clear that more research is needed to inform policy. But according to Krolikowski, an assistant professor of science and technology policy at Missouri S&T, a hypothetical foundation already exists that could lead to a broader legal regime (linked to good old-fashioned business sense).

For example, the Outer Space Treaty and the Artemis Accords emphasize that activities on the moon must be consistent with international law. They are also responsible for the activities of third parties in areas of jurisdiction. Other than that, a number of legal questions need to be addressed, but efforts are underway to ensure that this happens in advance of any lunar settlement.

For example, you have organizations like the Space Court Foundation (SCF), an educational nonprofit founded by legal scholars and space experts, dedicated to communicating about the evolving domain known as “Space Law”. As we addressed in the previous article, the Foundation is also creating an archive where the most up-to-date version of the relevant documentation and scope laws can be found.

According to Krolikowski, the second step that needs to be taken is to call on the parties that will actively search for identified resource sites within the next decade or so. The most important issues to pay attention to are damage-barriers, where strategies can be developed to prevent congestion, interference and other bad situations at individual sites.

In addition, insights can be given by examining research on comparative sites on Earth. Krolikowski said:

“Examples of analogues on Earth point to methods for managing these challenges. Common-pool resources on Earth, resources on which no single workspace or ownership can be claimed, give insight to the gummy. Some of these are globally like seas, while others are local like fish stocks or lakes into which some small communities enter. ”

So far, several space agencies have announced plans to build a permanent human outpost on the moon – including NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), China National Space Administration (CNSA), Roscom and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JXA). . There are also numerous plans to set up centers that allow lunar tourism and other commercial ventures.

For each of these schemes, the sites must be well-planned in advance to determine whether they have the right balance of resources. This is not only necessary to create and maintain the necessary creations, but it also ensures that they can meet the needs of their professionals in a way that is sustainable. But with limited sites and resources to function, action needs to be there to ensure that we don’t end up fighting where we are.

Just one more challenge that humanity must first focus on is to re-plant its boots and flag on the moon. But on the plus side, it shows how close we are to becoming an “interdisciplinary culture.” The fact that we are at this stage where we must consider how to resolve legal and territorial disputes on the moon shows how close we are to returning to live there.

Regardless of how we choose to tackle this issue, the next two decades will definitely be an interesting time to stay alive!

Further reading: CFA, The Philosophical Practices of the Royal Society a