The Trump administration has highlighted an apparent disconnect between rising cases and declining mortality as proof that the Covid-19 pandemic is under control.

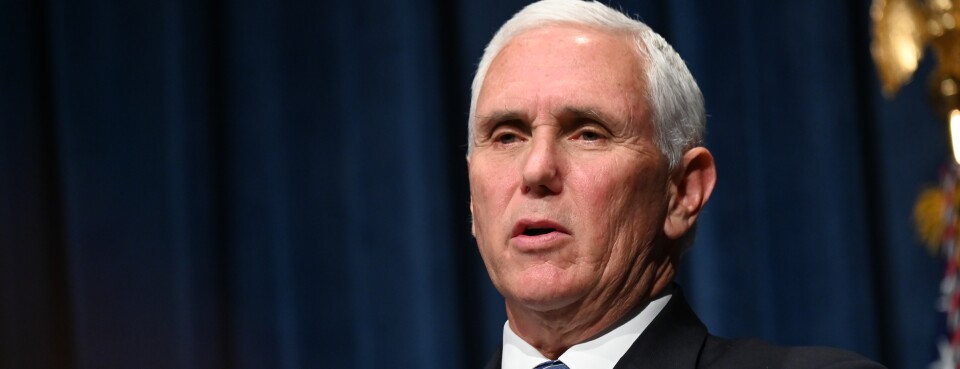

“Deaths are decreasing across the country,” Vice President

However, the mismatch appears to be more of an anomaly caused by quirks in the way death data is collected and reported, along with a higher number of younger people contracting the infection, than a sign that the coronavirus it is becoming less lethal or easier to treat.

Nationwide, the number of deaths increases by 600 to 700 per day, even when record numbers of new cases were diagnosed this week. That is well below the height of the pandemic when more than 2,500 deaths were reported some days. Medical experts say it is too early to know for sure that deaths continue to decline.

That disparity prompts health experts and the public to ask questions: Is it because those who get sick now are younger than those who got sick in March and April? Are we getting smarter about using fans? Are new medications like Gilead Sciences Inc.’s remdesivir helping? Are the cases milder due to the warm weather?

“The uncertainty right now is as high as it has been since the first scary days in mid-March,” said James Scott, professor of data science at the University of Texas at Austin. He is part of a team of models from the University of Texas that predicts that deaths will increase in July.

To complicate matters, there can be a delay of several weeks in many states between when someone dies and when that is included in the daily reports. That means deaths could be increasing days before states say yes.

It’s not just mortality statistics that can’t be completely trusted: basic information, like new daily hospitalizations related to Covid-19, isn’t reported by many states, among other key data points that could help scientists to predict which direction the death tolls are. Vault.

“We have a very heterogeneous pandemic experiment right now: Different parts of the country and different states are experiencing very different things,” said Jeffery Morris, director of the biostatistics division at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “It is a kind of paradox.”

So while it’s too early to see what the death toll will be from the recent increase, if the exponential growth in cases continues unabated, the increase in deaths is almost inevitable.

“This particular part of the epidemic is just taking off, and we are still on track,” said Thomas Giordano, head of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “The last thing that happens is death. We’re just not that far off with this one yet. “

Time delay

Deaths are the last lagging indicator, especially with Covid-19. It takes several weeks after diagnosis for a patient to die. Then it takes doctors, sometimes weeks, more time to complete death certificates and health officials to judge deaths. Only then are they finally added to the official state account.

“You can’t see the deaths as an indicator of where the outbreak is in this particular time period,” said Amesh Adalja, principal investigator for the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Safety.

Waiting for the data to arrive requires “patience that is difficult to muster during a crisis,” said Joe Gerald, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Arizona. But “if you want reliable and complete data, you should expect it, especially in cases of death.”

In Arizona, the time between diagnosis and death of Covid-19 is now approximately 14 or 15 days, compared to the first four or five days of the pandemic. Then the state health department must verify the death, so there may be a delay of more than three weeks between a new case and a reported fatality, Gerald said.

Half of the reported deaths for the week ending June 14 were more than a week old, so he expects it to take at least another week before reaching conclusions about the death rate from this increase. A modest blow could be expected with younger hospitalized patients at a higher hospitalization rate, Gerald said.

Younger age

Approximately 80% of deaths have been people 65 and older, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, fewer than 10% have been under the age of 45. This has led people like Pence to predict that there will not be many deaths as the virus is now infecting more younger adults.

In Florida, where reported cases soared 7.8% on Friday, while deaths rose 1.2%, the average age of patients fell to 37 in mid-June from more than 60 in mid-March. Deaths have stagnated due to a “drastic change in the age of infected people,” said Jill Roberts, an associate professor at the University of South Florida School of Public Health who specializes in emerging diseases. “Healthy people who are less likely to suffer serious consequences are responsible for the majority of cases.”

She partly blamed the crowds at the reopened bars. “Indoors, where no one wears masks, where people may be yelling or screaming for music, all of those things create the perfect setting” for the viral spread.

On Friday, the state banned drinking alcohol in bars.

But if older people were more cautious and younger people reduced the average age of patients, it would lead to fewer hospitalizations. So far, they are increasing in Florida, suggesting that this is not the only thing that is happening.

The great danger is that as more young people become infected, it will spread to the elderly. That’s especially true in Florida, where one in five residents is over 65. Did younger Floridians, with asymptomatic or presymptomatic cases, visit their parents or grandparents on Father’s Day and infect them?

“My biggest concern is what happens in two weeks,” said Roberts. “People who are seeing key cases now could infect other people. And if they infect other people, we will see hospitalizations and deaths below. ”

Improved care

Better treatments could also explain the gap. Remdesivir, approved in an emergency in May, helps hospitalized patients recover about four days faster. A study suggests that it may also reduce the death rate. It is now used in hospitals along with convalescent plasma, a type of blood collected from survivors that may contain antibodies to the virus. And just this month, the steroid dexamethasone was shown to keep ventilator users alive in a trial led by the University of Oxford.

As doctors learned more about the disease, they discovered better strategies. Seriously ill patients have been found to benefit from being prone to the side or stomach.

“We have learned best practices from around the world, and there has been a real global exchange around the areas that have faced this epidemic in large chunks and what they have learned,” said Bill McKeon, president and CEO of Texas, based In Houston. Medical Center, which has seen the beds in its intensive care unit fill up as cases increase.

Milder summer cases or weakened virus

There is also a chance that cases will become milder, either due to changes in transmissibility in warmer climates or changes in the virus itself. Warm climate theory holds that warm, humid temperatures cause viral particles to fall to the ground faster.

Most of the attention has focused on whether the heat will reduce the total number of cases. But a more subtle effect of the weather may be that many patients are initially infected with a lower dose of the virus, leading to less severe symptoms, says David Rubin, director of PolicyLab at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Some researchers also think that Covid-19 may be less potent as it replicates. The hypothesis has gained a lot of attention since it was presented by Italian doctors a few weeks ago, but the claims are highly controversial.

The World Health Organization has disputed that the virus has mutated significantly.

To contact the authors of this story:

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Timothy Annett

© 2020 Bloomberg LP All rights reserved. Used with permission.