There is an idea that when the climate crisis begins, we will know. Movies present it as a moment when the weather of the world suddenly becomes apocalyptic: winds howl, sea levels rise, capitals become decimated. Climate reports may support this idea, implying that we have a certain number of years to save the day before we reach a cataclysmic point of no return.

Living in anticipation of a definitive global break can blind us to the fact that the climate crisis is slowly, sadly, already approaching.

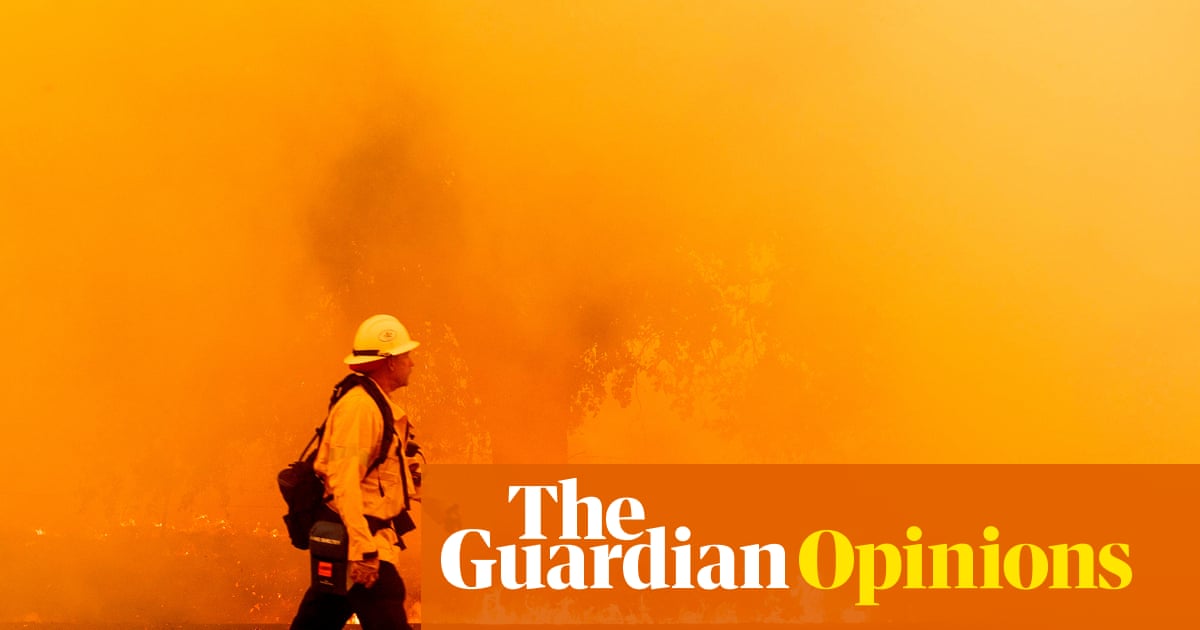

In a few places this is as clear as California, where extreme wildfires have become the new abnormal. There is currently a ‘fire siege’ in northern California, with fires burning in each of the nine Bay Area counties, except in San Francisco, which is fully urbanized. Tens of thousands of residents have been evacuated and people are choke over smoke.

The conditions of these blisters are unusual. It began with a tropical storm that receded in the Pacific Ocean, and wiped its feet in the direction of California. When it made landfall in the San Francisco area over the weekend, it caused a remarkable lightning storm, and 10,849 lightning strikes were counted in three days.

Over millennia, the California landscape has adapted to burn, with some tree species requiring the heat of flames to open their seed traps, and lightning-sparkling wildfires are not uncommon. But the state has experienced unusual heat, and recorded just the highest temperature ever recorded on Earth: 129.9F in Death Valley, a few hundred miles southeast of the Bay Area lightning. Vegetation is achingly dry and primary to ignite.

The governor of California announced Wednesday that there were 367 fires, and conflagrations have grown so fast that there are not enough firefighters to deal with them all. Neil Lareau, an atmospheric scientist, told us in an interview that he viewed the current fires with “unbelievability”.

“It seems like every year the previous year picks up again in terms of printing the envelope, in terms of how much fire we see in the landscape and how serious that fire is,” he said.

There were also, by the way, several fire tornadoes over the weekend. Witness these phenomena, another fire expert remarkable that California “is the model for extreme events of climate change today.”

In recent decades, in the midst of drought and warming heat, California has entered the “era of megafires.” Our new book, Fire in Paradise, tells the story of a city that was almost completely destroyed by a fire of unheralded speed in 2018. It killed 85 people, making it the deadliest fire ever in California. Other notable extinguishers include a 1,000-foot-wide tornado that swept through the city of Redding a few months before the catastrophe of Paradise, and fires in California’s Wine Country that killed 44 people.

All of this is why, if we scan the headlines for the planetary shift that will mark the real onset of the climate crisis, we lose the risk that places like California are already experiencing it.

This is not entirely surprising. According to the ecological theory of “displacement of baselines”, we do not notice the degradation of the natural world, because we are little by little accustomed to it, like a frog in hot water. We think it has always been so.

Once upon a time, for example, the passenger pigeon was the most abundant bird in North America, perhaps the world. Observers in the 19th century described large sheep so loud that you could not hold conversations and so large that they hid the sun: “The light of the afternoon was hidden as if by an eclipse”.

Yet they gradually disappeared, as a result of overpowering and destruction of habitat, into extinction, and most of us do not miss them because we never knew anything else. Our expectations of the natural world are simply different.

When it comes to wildfires in California, the ground has shifted under our feet for decades as heat rises, snippets shrink and plants dry out. The baseline has been shifted. How long before we forget it was ever different?

.