[ad_1]

December 21, 2015 was like today Monday. Smoke rose over the village of Rupperswil in Aargau. There was a fire in a two-family house. The fire department found four bodies. During Christmas days, the news spread that a family had been murdered here. It was the beginning of one of the most important persecution campaigns in Switzerland. It lasted 146 days. Only then was the quadruple killer Thomas N.

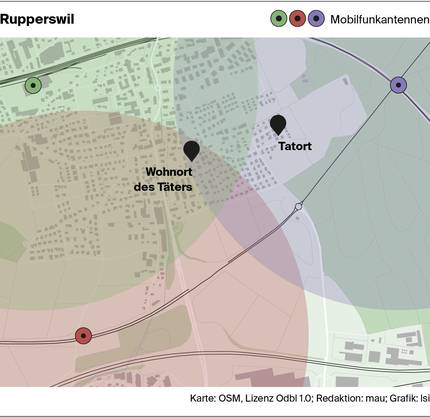

With the Rupperswil case, a new search method became known: the antenna search. The Public Ministry and the Criminal Police evaluated the data from three cell phone masts near the crime scene. It contained the cell phone numbers of around 30,000 people whose devices had been connected to antennas in the hours around the crime. They can be calls, messages, or data connections from applications running in the background. The number of registered numbers is so great because all three antennas are on the railroad line and on the highway.

The search for antennas has been a success story ever since. Recognized experts spread the story that the aggressor was identified using this method. The researchers had no interest in denying this legend because the alleged success helped justify and fund future antenna searches. Because the method is very expensive. The federal government first charged the canton 816,000 francs for this, sparking a legal dispute.

The truth is that the antenna scan was useless in this case. Investigators found no evidence leading to the perpetrator. His cell phone number was in the data pile. The researchers only recognized the famous needle in the haystack when they identified the killer in another way and compared its number with the antenna data. They had another test, which they did not use in the process.

The state secret: why we still don’t know exactly

The investigation of this newspaper is based on sources from the police and the prosecution. Some cops are talkative because they are upset by the legend. Suggest that the computer programs solve the case or the office data specialists. It was the more than a hundred men and women on the streets of Rupperswil who did the classic police work. For example, they closely observed the contents of each garbage can within a kilometer radius and rang the bell at each front door in the area to show residents a desired maneuver. No direct leads were received, but the profilers were able to collect indirect leads. They saw how people reacted. They also called Thomas N. It is not known if he was suspicious. Police say the method at least moved the investigation forward, as opposed to the search for the antenna.

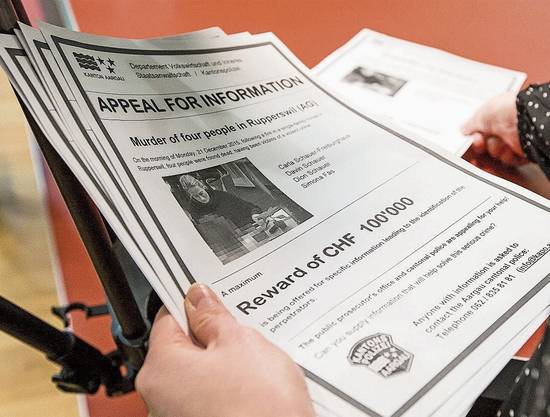

The pamphlet campaign: the police offered a reward.

© Keystone (Schafisheim, 02.18.2016)

What was the decisive approach in the end is a state secret and will remain so for the time being. Prosecutors want to prevent their actions from losing their surprise effect in future cases. For example, after a murder in Aarau in January 2019, the same method was used again, as it is called behind the scenes.

Therefore, no official confirmation is available to refute the myth. Given this, the two main investigators of the case make significant statements. Markus Gisin, chief of the Aargau criminal police, says: “It was not the only method that led us to the perpetrator. It was a mixture of different investigations. “And prosecutor Barbara Loppacher adds:” Searching the antenna alone is not usually enough to solve serious crimes. “

Markus Gisin spoke for the first time in detail about the quadruple murder in Rupperswil on the TalkTaily program on Tele M1 last week:

The method: when it’s successful and when it’s not

The antenna search is the ideal method to search for criminals who have struck in various places or at different times. Your cell phone data is recorded by various antenna searches. The intersection of the two series of numbers is so small that it only consists of the perpetrator’s data. A series of attacks on money carriers in Vaud were clarified. Perpetrators always left the same data trail at crime scenes.

In the Rupperswil case, however, there was only one crime scene and only one crime scene. Passenger traffic could be filtered out of antenna search. But there were still hundreds of numbers left, basically the phone book of all Rupperswil residents who turned on their cell phones on December 21. These numbers would only have been useful if they had been compared to others and the mountain of data could have been reduced to a small overlap. In the Rupperswil case, there was no evidence of this.

The perpetrator: Thomas N. in court.

© Cornerstone (Schafisheim, 16.3.2018

Thomas N. had left his fingerprints and DNA at the scene, but these did not result in any results in the databases. Before writing it was literally the blank slate.

Regardless, it makes sense that the prosecution gave the expensive job, as it is only approved within six months of the crime. The researchers secure the data so that it does not fail within a time frame. In addition, the processing is time-consuming as mobile phone providers deliver the numbers in different formats.

But how did the legends come about? The same leading researchers gave the impetus by always emphasizing the advantages of antenna hunting and omitting the fact that it primarily provided a salad of worthless data without the right ingredient. Then the first media reports appeared, suggesting that the search for the antenna had been successful.

Science: why I wanted to believe in the fairy tale

St. Gallen professor of criminal law Marc Forster took up the thesis and disseminated it as fact in a specialist article. He is the expert in this field. Because he also works as a secretary in the Federal Supreme Court, where he formulated the reference ruling on antenna searches. At the same time, he is a fan of the method. In the case of Rupperswil, he saw an opportunity to finally confirm the success he had always hoped for. Then it happened that he wrote a contribution that did not meet scientific standards. In crucial places it has no sources.

It is astonishing, however, that Forster found renowned editors for his publication, namely criminal law professors Daniel Jositsch and Christian Schwarzenegger. Therefore, the thesis was scientifically proven and later adopted and even refined by the late St. Gallen prosecutor Thomas Hansjakob in his standard work on surveillance law. The work is in all prosecution offices because it is a practical manual with model provisions.

In the law libraries of Swiss universities, the volume is also placed on the shelf with the basic literature. The false report has thus been consolidated in the center of science, which has maintained its diffusion in the media.

The Rupperswil case thus became the “mother of all digital investigations.” The legend was believed because people wanted to believe it. The fact that it was a miscarriage was politely concealed.

There were initial indications that the search for the antenna did not lead to a breakthrough. It must have been the question of who knew how the intersection works with this method. In addition, the canton distributed the unclaimed bonus of 100,000 Swiss francs for information to the investigators and did not use it to cover the antenna search costs. The high bill wouldn’t have bothered him so much had he solved one of the most brutal crimes.