Microbes were found buried in the earth 101.5 million years ago, even before Tyrannosaurus rex when Earth’s largest carnivorous dinosaur, called Spinosaurus, roamed the planet. Time passed, continents changed, oceans rose and fell, great apes emerged, and eventually humans evolved with curiosity and the skills to unearth those ancient cells. And now, in a Japanese laboratory, researchers have revived single-celled organisms.

Investigators aboard the JOIDES Resolution drilling vessel collected sediment samples from the ocean floor 10 years ago. Samples came from 328 feet (100 meters) below the 20,000-foot-deep (6,000 m) bottom of the South Pacific gyre. That’s a region of the Pacific Ocean with very few nutrients and little oxygen available for life to survive, and researchers were looking for data on how microbes are carried in such a remote part of the world.

“Our main question was whether life could exist in such a nutrient-limited environment or whether it was a lifeless zone,” Yuki Morono, a scientist at the Japan Agency for Science and Technology of Marine Land and lead author of a New article on microbes, said in a statement. “And we wanted to know how long microbes could sustain their lives in the absence of food.”

Related: The oldest living beings on Earth immortalized in stunning photos

Their results indicate that even cells found in 101.5 million-year-old sediment samples are able to wake up when oxygen and nutrients are available.

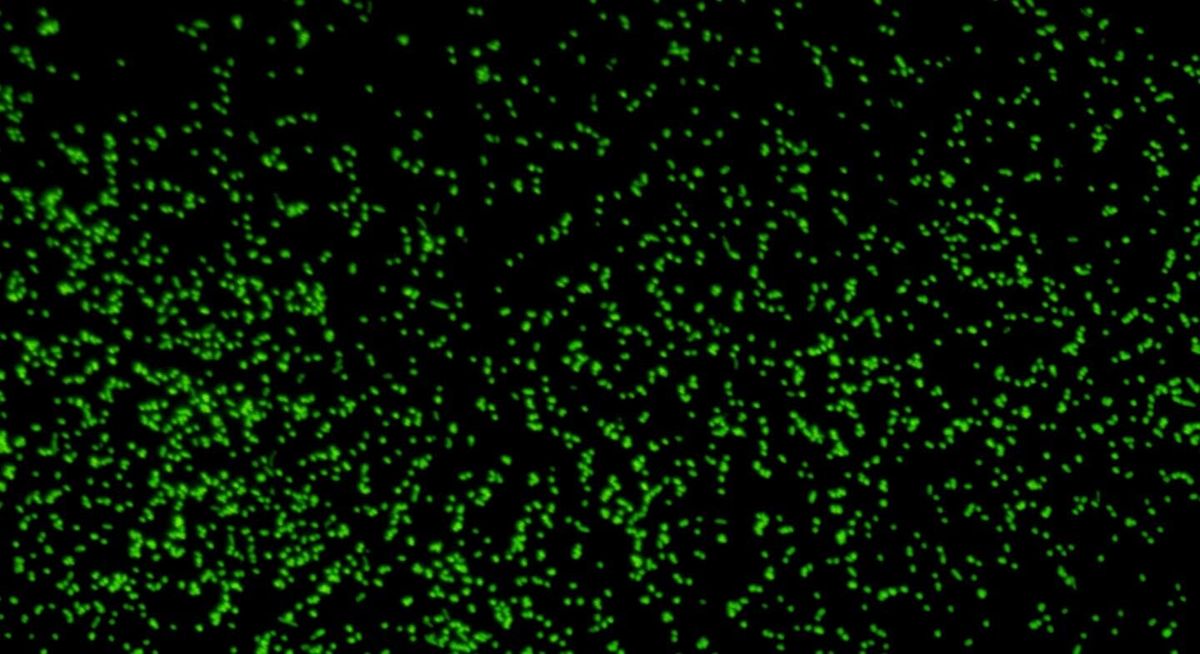

“At first, I was skeptical, but we found that up to 99.1% of the microbes in sediment deposited 101.5 million years ago were still alive and ready to eat,” Morono said.

The microbes had ceased all notable activity. But when they were offered nutrients and other necessities of life, they became active again.

To ensure that their sample was not contaminated with modern microbes, the researchers opened the sediment in a highly sterile environment, selecting the microbial cells present and feeding them exclusively with a small tube designed not to allow contaminants to enter.

The cells responded, many of them quickly. They quickly gobbled up nitrogen and carbon. Within 68 days, the total cell count had quadrupled from the original 6,986.

Aerobic bacteria (oxygen respirators) were the most resistant and most likely to wake up cells. These tiny organisms survived only in the tiny air bubbles that descended into sediment along geological time scales. It appears that the metabolic rate of aerobic bacteria is slow enough to allow them to survive for long periods.

The research was published July 28 in the journal Nature Communications.

Originally published in Live Science.