[ad_1]

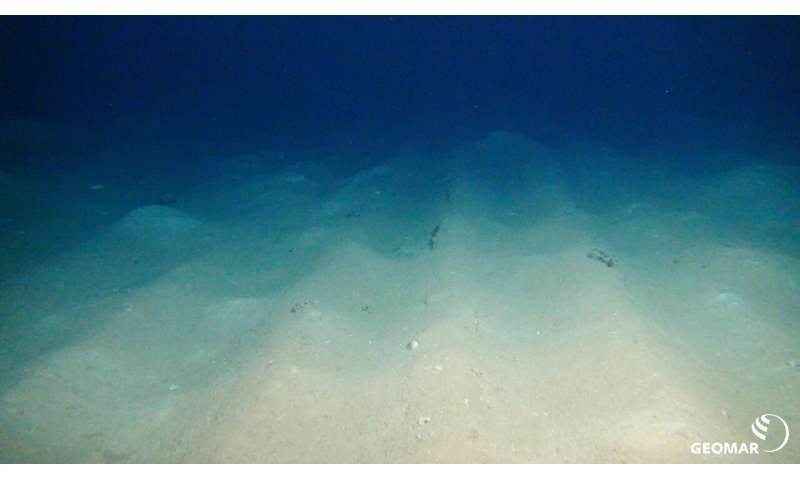

Sampling on a 6-year-old plow track in the DISCOL area. Credit: ROV-Team / GEOMAR

The environmental impact of deepwater mining is only partially known. Furthermore, there is a lack of regulations to regulate mining and establish binding thresholds for the impact on local organizations. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology with colleagues from the Alfred Wegener Institute, GEOMAR, and others describe that disturbances related to deepwater mining have a long-term impact on the functions of the natural ecosystem and microbial communities on the seafloor. .

Polymetallic nodules and crusts cover many thousands of square kilometers of the world’s deep sea floor. They mainly contain manganese and iron, but also the valuable metals nickel, cobalt, and copper, as well as some of the rare earth high-tech metals. Since these resources may become scarce on land in the future, for example, due to future needs for batteries, electromobility, and digital technologies, marine deposits are economically very interesting. To date, there is no market-ready technology for deepwater mining. However, it is already clear that interventions on the seabed have a massive and lasting impact in the affected areas. Studies have shown that many sessile inhabitants of the seafloor surface depend on nodules as a substrate, and are still absent decades after a disturbance in the ecosystem. In addition, the effects on animals living on the sea floor have been demonstrated. As part of the BMBF-funded MiningImpact project, the Max Planck Institute in Bremen has now taken a closer look at the smallest inhabitants of the seabed and their performance.

What about the smallest inhabitants of the seabed?

The present study shows that microorganisms that inhabit the seabed would also be greatly affected by deepwater mining. The team led by Antje Boetius, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and director of the Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research at the Alfred Wegener Institute, traveled to the area called DISCOL in the eastern tropical Pacific, about 3,000 kilometers from distance The coast of Peru to investigate the conditions of the seabed, as well as the activity of its microorganisms. In 1989, German researchers had simulated mining-related disturbances at this site by plowing the seabed in a three-and-a-half kilometer diameter manganese nodule area with a plow harrow, 4,000 meters below the ocean surface.

“Even 26 years after this disturbance, the footprints of the plow at the bottom of the sea were still clearly visible,” reports first author Tobias Vonnahme, who participated in the study as part of his diploma thesis. “And the bacterial inhabitants were also clearly affected.”

Compared to undisturbed regions of the seafloor, only about two-thirds of the bacteria lived in the old footprints, and only half of them on cooler plow tracks. The rates of various microbial processes decreased by three quarters compared to undisturbed areas, even after a quarter of a century. “Our calculations have shown that it takes at least 50 years for microbes to fully resume normal function,” says Vonnahme.

Undisturbed seabed with the low manganese nodule density typical of the DISCOL area. Credit: ROV-Team / GEOMAR

Dusty and messy

So deep and far from the strong currents on the sea surface, it is not so surprising that even the small-scale footprints of the DISCOL experiment were still visible. “However, the biogeochemical conditions had also undergone lasting changes,” says Antje Boetius.

According to the researchers, this is mainly due to the fact that the plow destroys the upper active sediment layer. It is plowed or agitated and swept away by currents. In these disturbed areas, microbial inhabitants can only make limited use of the organic material that sinks to the seafloor from the upper layers of the water. As a result, they lose one of their key ecosystem functions. Therefore, microbial communities and their functions may be appropriate as early indicators of damage to deep-sea ecosystems caused by nodule mining and the extent of their potential recovery.

The plow tracks where manganese nodules are plowed and sediment disturbed are still clearly visible after 26 years. Credit: ROV-Team / GEOMAR

Disturbance in another dimension.

All of the mining technologies for manganese nodules that are currently being developed will lead to a massive disturbance of the seafloor to a depth of at least ten centimeters. This is comparable to the disturbance simulated here, but in completely different dimensions. Commercial deep-water mining would affect hundreds to thousands of square kilometers of sea floor per year, while all plow tracks in the combined DISCOL only cover a few square kilometers. The expected damage is correspondingly greater, and would be correspondingly more difficult for the ecosystem to recover, the researchers emphasize.

“So far, only a few studies have addressed the disruption of the biogeochemical function of deep-sea bottoms caused by mining,” explains Boetius. “With this study, we are contributing to the development of environmental standards for deepwater mining and pointing to the limits of seabed recovery. Ecologically sustainable technologies should definitely avoid removing the densely populated and bioactive surface layer from the seabed. “

The study is published in Scientific advances.

What vision do we have for the depths of the sea?

“Effects of a deep-water mining experiment on communities and microbial functions of the seabed after 26 years” Scientific advances (2020). DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.aaz5922, https: //advances.sciencemag.or … ontent / 6/18 / eaaz5922

Provided by

Max Planck Society

Citation:

Simulated deepwater mining affects ecosystem functions on the seafloor (2020, April 29)

Retrieved on April 29, 2020

from https://phys.org/news/2020-04-simulated-deep-sea-affects-ecosystem-functions.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair treatment for the purpose of study or private investigation, no

part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]