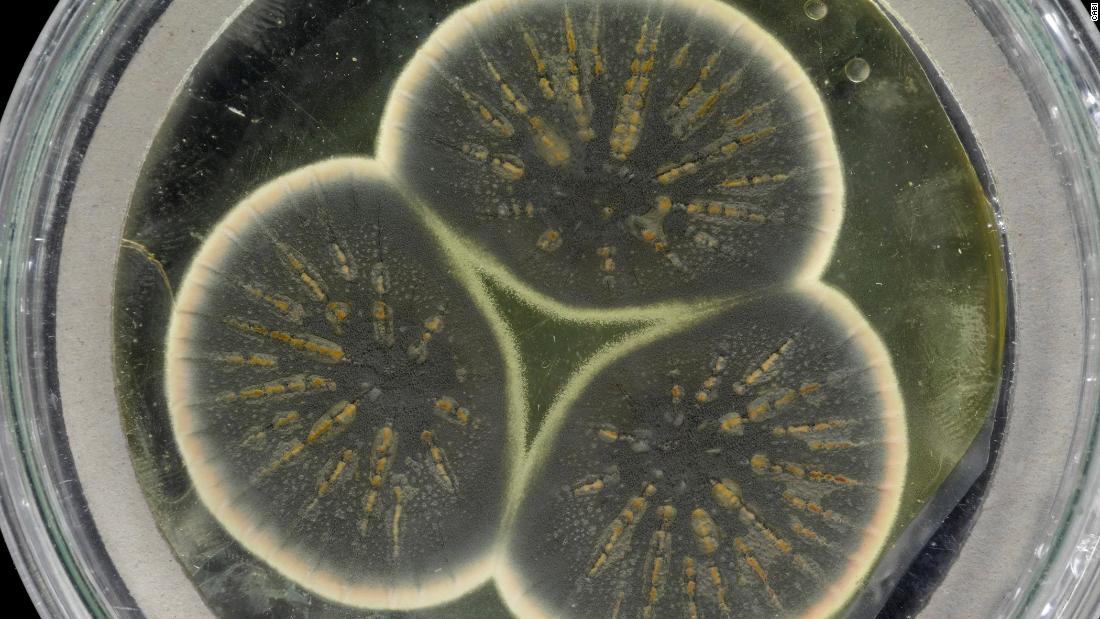

Now, scientists have awakened Fleming’s original Penicillium mold and sequenced its genome for the first time. They say the information they have collected could help in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

“It’s worth noting that after spending all this time in the freezer, it goes back quite easily. It’s fairly simple, you just break it out of that tube and put it on a Petri dish plate and it goes,” said Tim Barrackloff, a professor. In the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College College London and in the Department of Zoology at Oxford University.

“We are surprised that, despite the historical significance of the field, no one has indexed the genome of this original penicillium.”

Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928 while working at St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School, now part of Imperial College London.

The battle against the superbug

The team used genetic information to compare Fleming’s ghat with two species of Penicillium in the United States to produce antibiotics on an industrial basis.

Barclays said they are looking for differences that have evolved naturally over time that will shed light on how antibiotic production can improve in the fight against superbugs.

“It can give us some suggestions on how we can try and improve the formulation of antibiotics or our use to fight bacteria.”

“There’s been a lot of effort in finding new classes of antibiotics. But then when it’s used by everyone, the same thing happens over a period of time – after five or 10 years you’ve got that resistance,” he added.

His team was looking at “the subtle differences in the class of antibiotics and how they can vary in nature and whether we can use those more subtle differences to change the balance a little bit to eliminate these bacteria.”

He said, “There may come a time when penicillin can be bought in any shop. “Then there is the fear that an ignorant man can easily outgrow himself and make his resistant by exposing his microbes to unhealthy amounts of the drug.”

.