Yuri Dmitriyev will be released in November due to the time served.

A Russian court sentenced a historian who helped uncover mass graves from Stalin’s “Great Terror” campaign to 3.5 years in prison, on charges widely criticized by human rights groups as fabricated and viewed as part of an effort by Russian authorities to whiten dark chapters. of the Soviet history of the country.

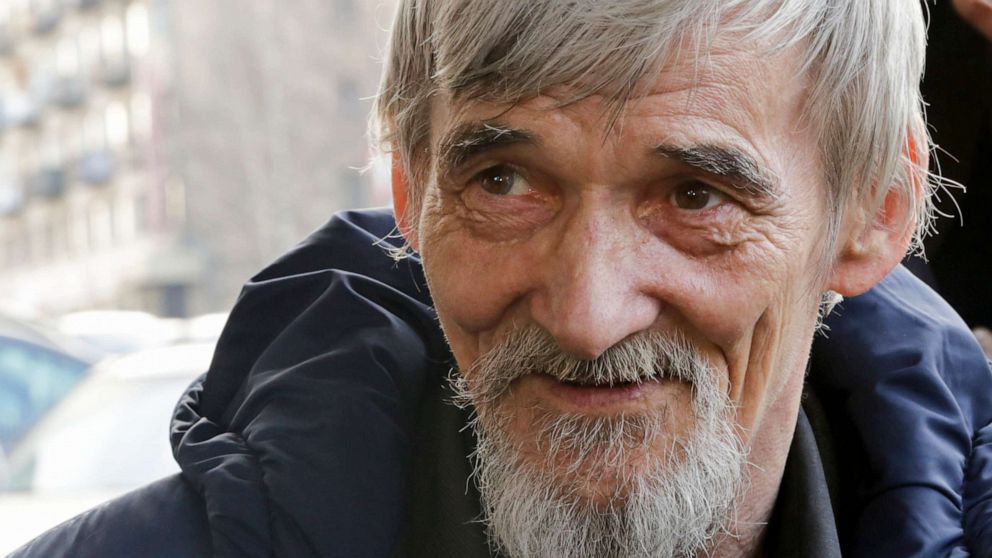

However, the historian Yuri Dmitriyev avoided what his supporters had feared would be a much longer prison sentence. Prosecutors sought a 15-year prison sentence for Dmitriyev, but the court decision means that due to the time already served, he will be released in November.

Dmitriyev, 64, heads a local branch of Memorial, a human rights group that commemorates victims of Soviet repression. He has been facing criminal prosecution since 2016, when police accused him of taking pornographic photographs of his adopted younger daughter.

A court in April 2018 acquitted Dmitriyev of the charges, but a higher court reversed the ruling and ordered a further investigation. In 2018, the police filed the case once again and added a new charge alleging that he had violently sexually abused his daughter. Dmitriyev was arrested and placed in preventive detention.

An expert witness told the court that the photographs were not pornographic and that psychological evaluations have shown no evidence that Dmitriyev is a pedophile. Dmitriyev said he took the photos to document the girl’s health in order to demonstrate to child welfare officials that she was well cared for.

International and Russian human rights groups have condemned the trial as an attempt to defame one of the country’s most prominent investigators of the mass graves of victims killed under Joseph Stalin.

On Wednesday, the court in the Karelia region where Dmitriyev lives sentenced him on the charge of violent sexual abuse, sentencing him for 3.5 years. But he acquitted him of the original pornography charges.

Dmitriyev’s supporters expressed disgust at the court’s decision, but hailed it as a victory because he will soon be released.

“The absolute groundlessness of the allegations was obvious from the start. And that sentence for such a serious accusation means one thing: that there is no evidence of Dmitriyev’s true guilt,” Memorial wrote in a statement.

“However, these allegations have already taken more than three years from Yuri Dmitryev’s freedom and have paralyzed the fate of his adoptive daughter,” the statement continued.

“By today’s standards, this is as good as they absolved him,” wrote Evgeny Roizman, a prominent opposition politician on Twitter.

Dmitriyev’s case has drawn international criticism. Human Rights Watch has previously called the charges “false.” In May, the British government said it was “deeply concerned” about his arrest.

Dmitriyev’s prosecution has coincided with an effort to alter the history of the graves in his region, Karelia, which borders Finland.

In the 1990s, Dmitriyev and others discovered a series of mass graves linked to Stalin’s Gulag prison system in Russia. A grave in Sandarmokh contained the bodies of more than 6,000 prisoners killed by the Soviet secret police during the “Great Terror” (also known as the “Great Purge”) between 1937-38.

But in recent years, a state-backed group has made an effort to suggest that the Sandarmokh tombs also contain the bodies of Red Army prisoners of war executed by Finnish troops during World War II.

The theory is being promoted by the Russian Military-Historical Society, an organization known for its nationalistic outlook and whose members include many senior officials of the Russian government. In 2018, members of the organization dug graves and found 16 bodies of soldiers who they believe prove that the Soviet secret police were not the only ones involved in the murder in Sandarmokh.

Critics say the effort is intended to muddy the waters around the graves and draw attention away from the Stalinist mass killings. It is presented in the context of a broader campaign under President Vladimir Putin in recent years to downplay the importance of Soviet crimes in Russian history and to rehabilitate Stalin’s image.

Memorial has faced a series of dubious criminal investigations in recent years. Last year, activists at the Perm Memorial in central Russia were accused by police of “illegal logging” for cutting bushes around a cemetery where Lithuanians and Poles displaced under Stalin are buried. The organization, which also campaigns against current abuses, has also seen its offices raided and its members have faced intimidation.

.