A paper released this week by Urbana-Champaign astronomy and professor of physics at the University of Illinois, Brian Fields, makes a case for distant supernovae as the cause of a past mass extinction event – specifically the Hangenberg event, which borders marks between the Devonian and Carboniferous periods. Fields has suggested this kind of thing before, and both this and his earlier piece are fascinating exercises of “what-if.” Each models the effects that a supernova can have on the Earth’s biosphere, and how we can go in search of evidence that it happened.

However, it is important to understand that none of these papers should be taken as indications that there is evidence that the referenced events were caused by a supernova, or as a representative of any general scientific consensus on that effect. These are just interesting proposals, and they indicate what kind of evidence we should seek.

Existing threats

If you say “mass extinction” and “space” in the same sense, the first thing on the minds of most peoples is an asteroid impact on Earth – even if dinosaur fans think of the Chicxulub crater, and fans of pop culture think instead of movies like Deep impact of Armageddon.

However, asteroid impact is not the only threat that the Earth has from space – and the Cretaceous-Paleogene is not the only mass extinction event that the Earth has experienced. An even larger event of mass extinction occurred 359 million years ago – it is called the Hangenberg event, which marks the boundary between the Devonian and Carboniferous periods. The Hangenberg event affected both marine and terrestrial biomes, destroying 97 percent of all vertebrate species.

An asteroid impact has been advanced as a probable cause of the Kellwasser extinction event, which occurred about 10 million years earlier. But no significant impact has been discovered that dates back to the exact period for the Hangenberg event. Several other potential mechanisms have been proposed, including side effects of significant changes in plant life and massive atmospheric injections of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide due to magmatism. But so far there is no “smoke gun” that directly points to a case.

Ozone depletion

What we do know about the Hangenberg extensions is that they occurred over thousands, and perhaps hundreds of thousands of years. We also have evidence of ultraviolet damage to pollens and spores over several thousand years during this event, and this in turn points to a possible long-term destruction of the ozone layer.

The length and severity of this period of ultraviolet damage probably governs most local causes of ozone depletion. Ozone depletion due to terrestrial causes, such as increased stratospheric water vapor due to higher surface temperatures, is probably not severe enough to result in the large-scale extinctions seen during this period.

Meanwhile, the ozone layer typically recovers from more local catastrophic astrophysical events – such as bolide impact, solar flares, and gamma-ray bursts – in ten years or so, which does not count for the severity of the duration of the Hangenberg extinction.

Fields’ team suggests that a supernovae may be responsible for both the severity and duration of the Hangenberg extinction.

The influence of the biosphere of distant supernovae

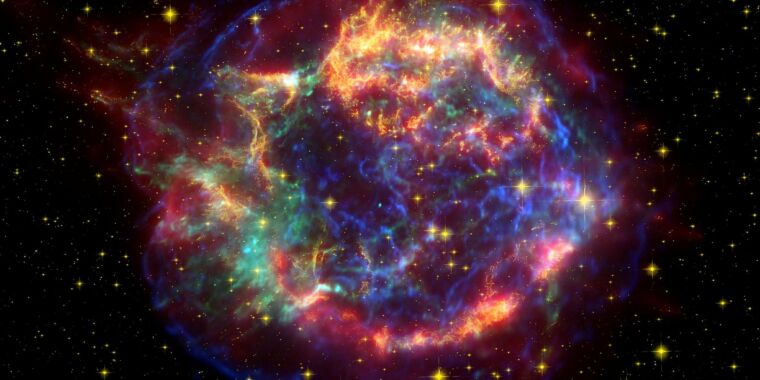

Supernova events are popularly imagined as an instantaneous one – a supermassive star explodes, and a radiation wavefront immediately boils enough items nearby as it continues. Within 25 light-years or so – much closer than any supernova threat to our solar system today – this is close enough to be precise.

However, the impact of a supernova event can be felt (and potentially extinction events) far beyond this relatively narrow “kill radius.” In 2018, another team led by Fields tried to link periods of diminished biological diversity and increased extinction rates 2.5 million years ago – on the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary – to a likely supernova event. This paper hypothesized a supernova that occurred between 163 and 326 light-years away, based on globally elevated levels of Iron-60, a radioactive isotope produced during supernovae. But the extinctions coincide with a period of great climate change, so it is not clear that a supernova would be needed to explain them.

For this new work, the team used global climate, atmospheric chemistry, and radiative transmission models to investigate how the flux of cosmic rays from a distant supernova would alter the ozone layer. Thomas told the journal Astrobiology that the impact of a distant supernova does not come at the same time. Instead, the intergalactic medium slows down some particles more than others, resulting in a “radioactive iron rain” that can last for hundreds of thousands of years.

The key to demonstrating that a supernova occurred in the exact time frame to explain the older and more destructive Hangenberg event would be discovery of the radioactive isotopes plutonium-244 and samarium-146 in rocks and fossils that were deposited during the event. Both isotopes occur naturally on Earth, and Fields describes them colorfully as “green bananas.”

“When you see green bananas in Illinois,” Fields said, “you know they’re fresh, and you know they’ve not grown here.” The period of decay of Pu-244 and Sm-146 is long enough for detection after 360 million years, but short enough to prevent their inclusion in the original formation of the Earth. Fields further says that discovery of these isotopes today “means that they are fresh and not from here – the green bananas of the isotope world – and thus the smoke guns of a nearby supernova.”

PNAS, 2020. DOI: 10.1073 / pnas.2013774117