[ad_1]

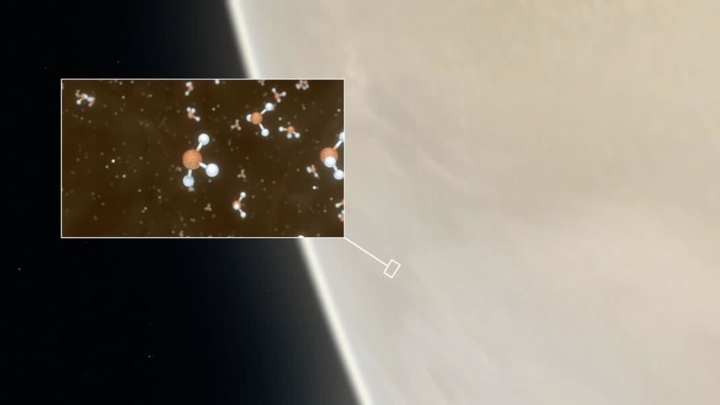

Phosphine is the common name for phosphorous hydride (PH3) and the detection of this element in the clouds of Venus “indicates potential for life.” It does not mean that it has life on Venus, because phosphine has already been found on other planets and even comets. However, this novelty may bring a new approach to the study of the planets where this gas is found.

Broadly speaking, on our planet, the production of this gas is related to biological sources, that is, organisms.

Is phosphine a sign that there is life on Venus?

Today, an international team of astronomers announced the discovery of a rare molecule, phosphine or phosphorous hydride, in the clouds of Venus. As we know, on Earth, this gas is only manufactured industrially or by microbes that thrive in anaerobic environments, that is, without oxygen.

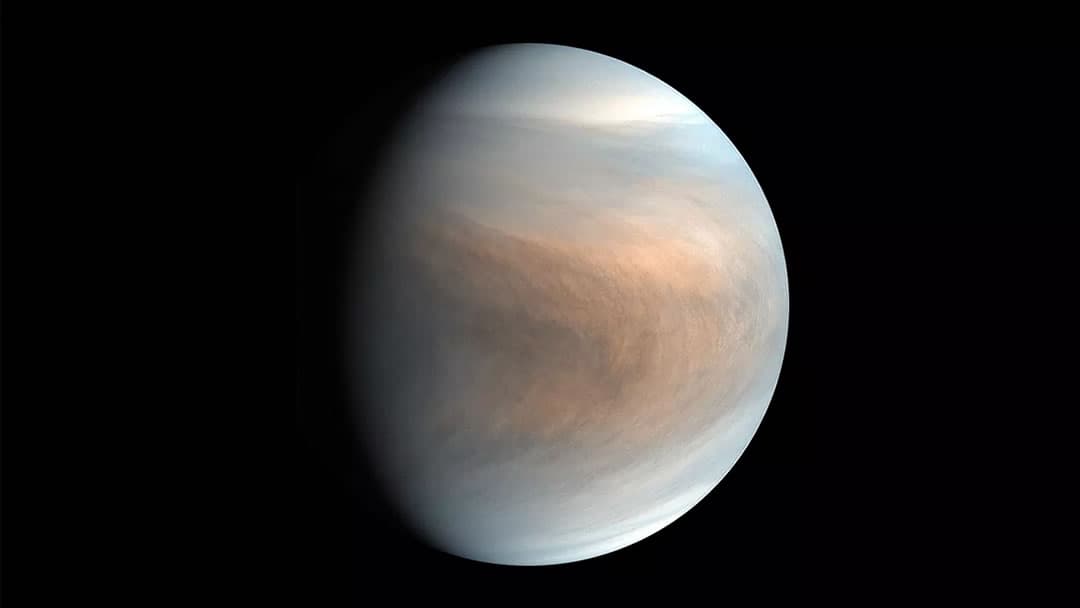

For decades, astronomers have suspected that microbes may be present in high clouds on Venus. These may be roaming freely and freed from the planet's scorching surface, but with the ability to tolerate very high acidity. The phosphine detection could point to extraterrestrial "airborne" life.

When we discovered the first signs of phosphine in the Venus spectrum, we were in shock!

He referred to team leader Jane Greaves from Cardiff University in the UK.

This team was the first to detect signs of phosphine in observations made with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT), operated by the East Asia Observatory in Hawaii. Thus, to confirm this discovery, 45 antennas from the Atacama Large Millimeter / submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, a much more sensitive telescope, were used.

Both infrastructures observed Venus at a wavelength of approximately 1 millimeter, much more than can be seen by the human eye; only telescopes placed at high altitude can detect these wavelengths effectively.

The clouds of Venus will have extraterrestrial life

According to the researchers, there may be phosphine, or phosphorous hydride (PH3), in small concentrations in the clouds of Venus, only about 20 molecules per billion.

After these observations, calculations were carried out to determine whether these quantities could originate in non-biological natural processes existing on the planet. Some ideas included sunlight, minerals rising from the surface into the atmosphere, volcanoes, or lightning, however it was concluded that none of these processes could even create the observed amount of phosphine.

Although explanations are possible, these non-biological sources can create a maximum of one-tenth of one-thousandth of the amount of phosphine observed by telescopes on Venus.

According to the team, to form the amount of phosphine observed on Venus, terrestrial organisms would only have to work at 10% of their maximum productivity. Terrestrial bacteria are known to create phosphine by removing phosphate from minerals or biological material, adding hydrogen, and ultimately releasing phosphine.

Any organism on Venus is likely to be very different from its terrestrial cousins, but they too could be the source of phosphine in the neighboring planet's atmosphere.

Image of the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) is a radio observatory composed of 66 antennas, 54 of which are 12 meters in diameter and the rest 7 meters in diameter.

Phosphine detection was a combination of elements in the right place

Although the discovery of phosphine in the clouds of Venus came as a surprise, the researchers are confident in its detection.

To our great relief, the conditions were right for ALMA follow-up observations, as Venus was at an appropriate angle to Earth. It is true that the data processing was complicated, since ALMA does not normally look for subtle effects in very bright objects like Venus.

In the end, we found that both observations had seen the same thing: a weak absorption at the correct wavelength for phosphine gas, even in the region where the molecules are illuminated from below by warmer clouds in the atmosphere.

Explained in the journal Nature Astronomy Anita Richards, a member of the team that works at the ALMA Regional Center.

In addition to this line of research, another investigated phosphine as a "bio-signature" of anaerobic life gas on planets orbiting other stars. This is because normal chemistry does not explain this phenomenon well.

Discovering phosphine on Venus was a real bonus. The discovery raises many questions, such as how organisms can survive in the atmosphere of the neighboring planet. On Earth, some microbes can support up to 5% acid in their environment, but the clouds on Venus are practically only acidic.

Explained the author of the research, Clara Sousa Silva of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States.

Saying there is life on Venus will still take a lot of work

The team believes this discovery is quite significant as it can rule out many other alternative phosphine formation processes. However, he acknowledges that confirming the presence of “life” still takes a lot of work. Despite temperatures hovering around a pleasant 30 degrees Celsius in the high clouds on Venus, the environment is extremely acidic, with about 90% sulfuric acid, posing serious difficulties for microbes trying to survive there.

Other observations of Venus and other rocky planets outside of our Solar System, including those obtained with the future of ESO's Extremely Large Telescope, can help gather clues about how phosphine is formed in these bodies and contribute to the search for signs of life. for beyond Earth.

[ad_2]