[ad_1]

Liu Fengfeng had more than a decade under his belt at one of the world’s leading tech companies before he realized where the real gold rush was taking place in China.

Computer chips are the brain and soul of all electronics produced by the nation’s factories. However, they are mostly designed and produced abroad. The Chinese government is wasting money on anyone who can help change that.

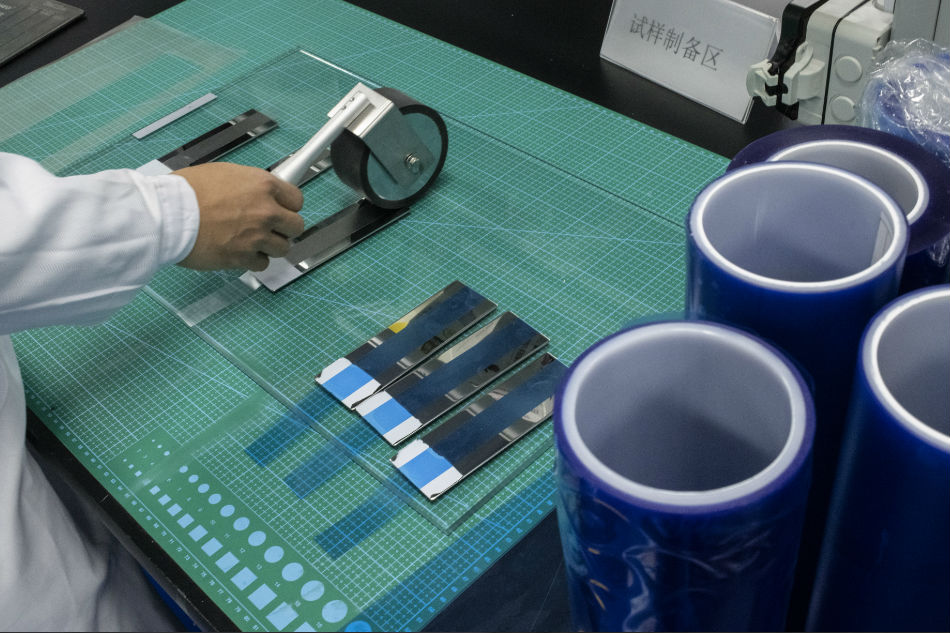

So last year, Liu, 40, left his job at Foxconn, the Taiwanese giant that assembles iPhones in China for Apple. It found a niche (high-end films and adhesives for chip products) and quickly raised $ 5 million. Today, his startup has 36 employees, most of them in the Shenzhen tech hub, and he aims to start mass production next year.

“Earlier, maybe you had to beg Grandpa and ask Grandma for money,” Liu said. “Now, he just has a few conversations and everyone hopes the projects will start as soon as possible.”

China is in the midst of a massive mobilization for token dominance, a quest whose goals may seem as far-fetched and impossible, at least until they are achieved, like sending rovers to the moon or dominating Olympic gold medals. In every corner of the country, investors, entrepreneurs and local officials are frantic to develop semiconductor capabilities, responding to a call from the country’s leader, Xi Jinping, to rely less on the outside world for key technologies.

Your efforts are beginning to pay off. China is far from home to real rivals from US chip giants like Intel and Nvidia, and its semiconductor makers are at least four years behind the forefront in Taiwan. Still, local companies are expanding their capacity to meet the country’s needs, particularly in products, such as smart appliances and electric vehicles, which have more modest requirements than supercomputers and high-end smartphones.

The push for turbocharged chips could prove to be one of the most enduring legacies of President Donald Trump’s pugilist trade policies toward China. By turning the country’s dependence on foreign chips into a club to attack companies like Huawei, the administration made Chinese business leaders and politicians decide never to be caught like that again.

But as Beijing broadens its semiconductor ambitions, it is also preparing for potential major failures and increasing the amount of money it could lose in the process. Several chip projects have recently run aground due to funding freezes and mismanagement. A state-backed chip conglomerate, Tsinghua Unigroup, warned this month that it was in danger of defaulting on nearly $ 2.5 billion in international bonds.

In a way, China hopes to achieve the same kind of take-off that helped it progress from making plastic toys to making solar panels.

With semiconductors, however, “the model is starting to falter a bit,” said Jay Goldberg, a technology industry consultant and former Qualcomm executive. The technology is incredibly expensive to develop, and established players have spent decades accumulating knowledge. Europe, Goldberg noted, once had many “incredible” chip companies. Japan’s chipmakers are leaders in certain specialty products, but few would call them bold innovators.

“My point is that there is a ladder, China is going up it,” Goldberg said. But it is not “clear to what result they go”.

Beijing’s recent love of chips began with the creation of a giant investment fund focused on chips in 2014. The government set a lofty goal: China would produce 40% of the chips it consumed by 2020. That did not happen. Morgan Stanley analysts estimate that Chinese brands bought $ 103 billion worth of semiconductors last year, of which 17% came from local suppliers. They predict that the proportion will rise to 40% in 2025, well below the government’s target of 70%.

China has moved ahead with renewed urgency due to the American assault on Huawei, the Chinese tech champion, which has been prevented from buying American chips or even chips made with American software and tools. The US Commerce Department imposed similar restrictions this month on exports to China’s most advanced chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., citing concerns over military ties. SMIC has denied that its products have any military use.

And so this year China has implemented new tax breaks for chips, including a 10-year exemption from corporate tax and duty-free imports of materials. State-backed funds have invested in both startups and publicly traded companies, including when SMIC listed shares in Shanghai in July.

At a high-level meeting on the economy in December, Communist Party leaders enshrined technological self-reliance as one of the country’s “Five Foundations” for economic development.

Yet total self-sufficiency in chips would mean recreating every part of the long supply chains for some of the world’s most complex technologies – a mission that would seem to lead, if not insane, then at least waste.

According to an analysis by China Economic Weekly, a magazine affiliated with the official Communist Party newspaper People’s Daily, the number of chip-related businesses in China increased by 58,000 between January and October this year, or about 200 per day. Some of these, the magazine noted, were in Tibet, not a place traditionally associated with cutting-edge technology.

“Until very recently, this year, the goal had been: With state support, move up the value chain, specialize where China has a comparative advantage, but don’t try to fall into the trap of trying to build everything yourself.” Said Jimmy Goodrich, vice president of global policy for the Semiconductor Industry Association, a group that represents American chip companies.

Now, “it is very clear that Xi Jinping is calling for a redundant national supply chain,” Goodrich said. “And so the rules of economics, comparative advantage, and supply chain efficiency have basically been discarded.”

The government is aware of the dangers. The state media has extensively covered the recent semiconductor blackouts. The message to other upstarts: don’t screw it up.

The New York Times, ANC, China, China chip, China semiconductors, China electronics, US-China tensions

[ad_2]