[ad_1]

RESEARCH. A team of medical research scientists. Photo from Shutterstock.com

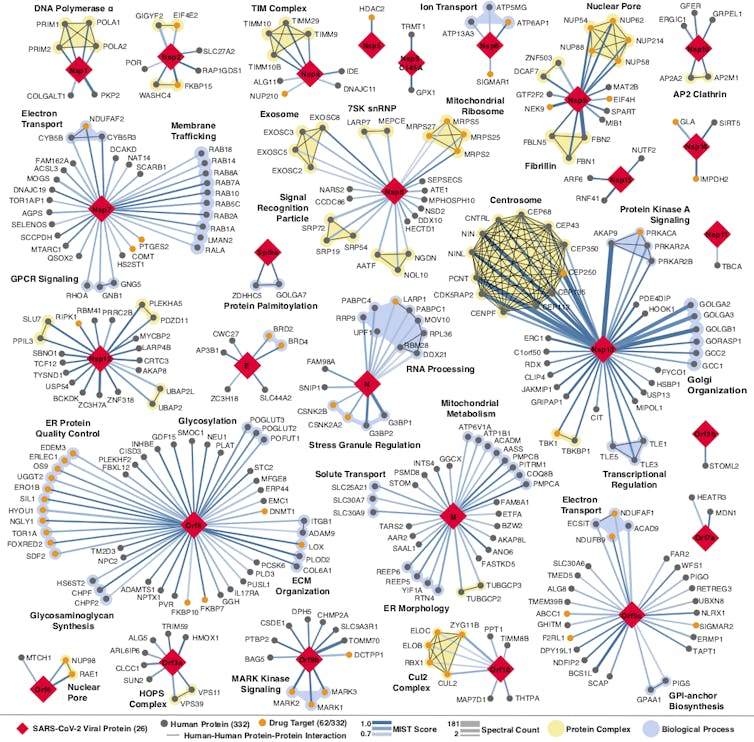

The more researchers know about how the coronavirus attaches, invades and hijacks human cells, the more effective the search for drugs to fight it. That was the idea my colleagues and I hoped to be true when we began building a map of the coronavirus two months ago. The map shows all of the coronavirus proteins and all of the proteins found in the human body that those viral proteins could interact with.

In theory, any intersection on the map between viral and human proteins is a place where drugs could fight the coronavirus. But instead of trying to develop new drugs to work on these points of interaction, we turned to the more than 2,000 unique drugs already approved by the FDA for human use. We believed that somewhere on this long list would be a few drugs or compounds that interact with the very same human proteins as the coronavirus.

We were right.

Our multidisciplinary team of researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, called the QCRG, identified 69 existing drugs and compounds with potential to treat COVID-19. A month ago, we began shipping boxes of these drugs off to Institut Pasteur in Paris and Mount Sinai in New York to see if they do in fact fight the coronavirus.

In the last 4 weeks, we have tested 47 of these drugs and compounds in the lab against live coronavirus. I’m happy to report we’ve identified some strong treatment leads and identified two separate mechanisms for how these drugs affect SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our findings were published on April 30 in the journal Nature.

Every place that a coronavirus protein interacts with a human protein is a potential druggable site. QBI Coronavirus Research Group, CC BY-ND

The testing process

The map we developed and the FDA drug catalog we screened it against showed that there were potential interactions between the virus, human cells and existing drugs or compounds. But we didn’t know whether the drugs we identified would make a person more resistant to the virus, more susceptible or do anything at all.

To find those answers we needed three things: the drugs, live viruses and cells in which to test them. It would be optimal to test the drugs in infected human cells. However, scientists don’t yet know which human cells work best for studying the coronavirus in the laboratory. Instead we used African green monkey cells, which are frequently used in place of human cells to test antiviral drugs. They can be readily infected with the coronavirus and respond to drugs very closely to the way human cells do.

After infecting these monkey cells with live viruses, our partners in Paris and New York added the drugs we identified to half and kept the other half as controls. They then measured the amount of virus in the samples and the number of cells that were alive. If the samples with drugs had a lower virus count and more cells alive compared to the control, that would suggest the drugs disrupt viral replication. The teams were also looking to see how toxic the drugs were to the cells.

After sorting through the results of hundreds of experiments using 47 of the predicted drugs, it seems our interaction predictions were correct. Some of the drugs do in fact work to fight the coronavirus, while others make cells more susceptible to infection.

It is incredibly important to remember that these are preliminary findings and have not been tested in people. No one should go out and buy these drugs.

But the results are interesting for two reasons. Not only did we find individual drugs that look promising to fight the coronavirus or may make people more susceptible to it; we know, at a cellular level, why this is happening.

We identified two groups of drugs that affect the virus and they do it two different ways, one of which has never been described.

Disrupting translation

At a basic level, viruses spread by entering a cell, hijacking some the cell’s machinery and using it to make more copies of the virus. These new viruses then go on to infect other cells. One step of this process involves the cell making new viral proteins out of viral RNA. This is called translation.

When going through the map, we noticed that several viral proteins interacted with human proteins involved in translation and a number of drugs interacted with these proteins. After testing them, we found two compounds that disrupt the translation of the virus.

The two compounds are called ternatin-4 and zotatifin. Both of these are currently used to treat multiple myeloma and seem to fight COVID-19 by binding to and inhibiting proteins in the cell that are needed for translation.

Plitidepsin is a similar molecule to ternatin-4 and is currently undergoing a clinical trial to treat COVID-19. The second drug, zotatifin, hits a different protein involved in translation. We are working with the CEO of the company that produces it to get it into clinical trials as soon as possible.

The coronavirus attacks human cells using dozens of devious tricks. narvikk / iStock Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

Sigma receptors

The second group of drugs we identified work in an entirely different way.

Cell receptors are found both inside of and on the surface of all cells. They act like specialized switches. When a specific molecule binds to a specific receptor, this tells a cell to do a specific task. Viruses often use receptors to infect cells.

Our original map identified two promising MV cell receptors for drug treatments, SigmaR1 and SigmaR2. Testing confirmed our suspicions.

We identified seven drugs or molecules that interact with these receptors. Two antipsychotics, haloperidol and melperone, which are used to treat schizophrenia, showed antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. Two potent antihistamines, clemastine and cloperastine, also displayed antiviral activity, as did the compound PB28 and the female hormone progesterone.

Remember, all these interactions have so far only been observed in monkey cells in petri dishes.

At this time we do not know exactly how the viral proteins manipulate the SigmaR1 and SigmaR2 receptors. We think the virus uses these receptors to help make copies of itself, so decreasing their activity likely inhibits replication and reduces infection.

Interestingly, a seventh compound – an ingredient commonly found in cough suppressants, called dextromethorphan – does the opposite: Its presence helps the virus. When our partners tested infected cells with this compound, the virus was able to replicate more easily, and more cells died.

Laboratory testing is excellent at generating leads but clinical trials must be done to know if these findings translate to the real world. Quantitative Biosciences Institute, CC BY-ND

This is potentially a very important finding, but, and I cannot stress this enough, more tests are needed to determine if cough syrup with this ingredient should be avoided by someone who has COVID-19.

All these findings, while exciting, need to undergo clinical trials before the FDA or anyone else should conclude whether to take or stop taking any of these drugs in response to COVID-19. Neither people nor policymakers nor media outlets should panic and jump to conclusions.

Another interesting thing to note is that hydroxychloroquine – the controversial drug that has shown mixed results in treating COVID-19 – also binds to the SigmaR1 and SigmaR2 receptors. But based on our experiments in both labs, we do not think hydroxychloroquine binds to them efficiently.

Researchers have long known that hydroxychloroquine easily binds to receptors in the heart and can cause damage. Because of these differences in binding trends, we don’t think hydroxychloroquine is a reliable treatment. Ongoing clinical trials should soon clarify these unknowns.

Treatment sooner rather than later

Our idea was that by better understanding how the coronavirus and human bodies interact, we could find treatments among the thousands of drugs and compounds that already exist.

Our idea worked. We not only found multiple drugs that might fight SARS-CoV-2, we learned how and why.

But that is not the only thing to be excited about. These same proteins that SARS-CoV-2 uses to infect and replicate in human cells and that are targeted by these drugs are also hijacked by related coronaviruses SARS-1 and MERS. So if any of these drugs do work, they will likely be effective against COVID-22, COVID-24 or any future iterations of COVID that may emerge.

Are these promising leads going to have any effect?

The next step is to test these drugs in human trials. We have already started this process and through these trials researchers will examine important factors such as dosage, toxicity and potential beneficial or harmful interactions within the context of COVID-19. – The Conversation | Rappler.com

[[The Conversation’s most important coronavirus headlines, weekly in a new science newsletter.]The Conversation

Nevan Krogan is a Professor and Director of Quantitative Biosciences Institute & Senior Investigator at the Gladstone Institutes, University of California, San Francisco.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]