[ad_1]

A 100-million-year-old piece of amber has revealed the oldest sample of animal sperm, and each individual cell is enormously long.

Even more impressive, this giant sperm, several times larger than human sperm, comes from a shrimp-like crustacean smaller than a poppy seed.

Just under 0.6 millimeters, this ancient bivalve belongs to a class of still-living microcrustaceans known as ostracods, which are famous for harboring sperm up to ten times their size.

That may seem impossible, but when these microscopic cells twist and become tangled into tiny pellets, they can travel through the female reproductive tract easily, fending off other smaller, competing tangles.

The studied piece of amber that shows the position of the specimens. (Wang et al., Proceedings B, 2020)

The studied piece of amber that shows the position of the specimens. (Wang et al., Proceedings B, 2020)

Using a micro-CT scanner, the researchers have now revealed 39 of their ancient crustacean relatives, all in the same slice of amber. Even more surprising, this frozen community still has some of the same reproductive traits that we see in ostracods today, including giant sperm.

Not only were their ancient relatives found with similar male “pegs,” these fossilized bodies also contained sperm pumps, eggs and, best of all, female receptacles filled with sperm.

“The fact that the female’s seminal receptacles are in an expanded state because they are filled with sperm indicates that successful copulation took place shortly before the animals were trapped in the amber,” the authors write.

Measurement of individual cells in these tangled masses is impossible, the authors admit, but claim that, at a minimum, the sperm are at least 200 µm long (0.2 mm). That’s at least a third of the total length of the ancient creature’s body.

It is also the oldest sample of animal sperm by far. While other ostracod fossils from a hundred million years ago have shown hints of giant reproductive organs, we have never before had a real sample from this time in our hands.

In 2014, 16 million-year-old freshwater ostracods were found, discovered in a cave in Australia, that contained 1.2 mm long sperm. But the new specimen, discovered in Myanmar, is 83 million years older. In fact, it is twice the age of the oldest unmistakable fossil animal sperm.

Throughout that time, ostracod reproduction appears to have remained largely the same: “a supreme example of evolutionary stasis,” as the authors put it.

During sexual reproduction, both ancient and modern ostracods probably use their fifth limb as a ‘hook’ to grasp females. Once they have it, they can insert their erectile tissue and pump an “exceptionally long but immobile sperm”, pushing it up two long sperm tubes in the female body.

Once these sperm reach the seminal receptacles, the authors think that they begin to move, establishing themselves in an “organized set” so that they can begin to fertilize the eggs.

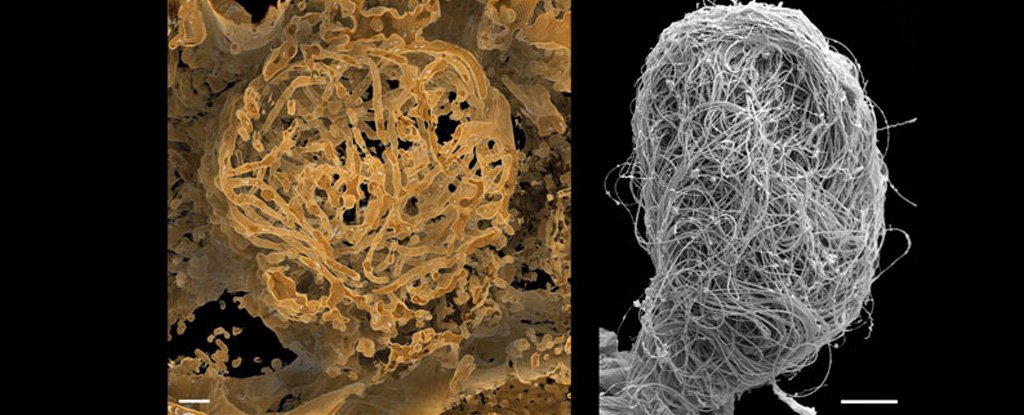

Ancient ostracod sperm in a female. (Wang et al., Proceedings B, 2020)

Ancient ostracod sperm in a female. (Wang et al., Proceedings B, 2020)

While it may sound counterintuitive at first, some of the smallest creatures on Earth produce some of the largest sperm. When females copulate with more than one partner, the sperm must compete; scientists believe that having larger units could be more advantageous. That said, giant sperm, such as ostracods, come at a high price for both men and women.

His sexual machinery simply has to be bigger in the first place, and for such a small animal, that’s a serious trade-off. Some modern species dedicate a third of their body volume only to reproduction.

As such, how this giant trait evolved and when it appeared remains a mystery. Direct evidence is really scarce. While crustaceans have calcified shells that leave a rich fossil record, it is extremely rare to find intact soft tissue in fossils.

This discovery is truly remarkable, not only because amber has preserved the soft tissues of various individuals for a hundred million years, but also because of all the similarities.

“The male classifier, sperm pumps, hemipenes, and female seminal receptacles with giant sperm from fossil ostracods reveal that the repertoire of reproductive behavior, which is associated with considerable morphological adaptations, has remained unchanged for at least 100 million years, “write the authors.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.