[ad_1]

His concern that the FDA is moving too fast increased when FDA Commissioner Dr. Steven Hahn told the Financial Times that his agency could consider an emergency use authorization (US) for a Covid-19 vaccine sooner. to complete late-stage clinical trials if the data show strong enough evidence that it would protect people.

Vaccine approval

Otherwise, the vaccines have had to go through the entire clinical trial process and the FDA approval process, which can take months or years.

When the vaccine manufacturing process has sped up, there have been poor results.

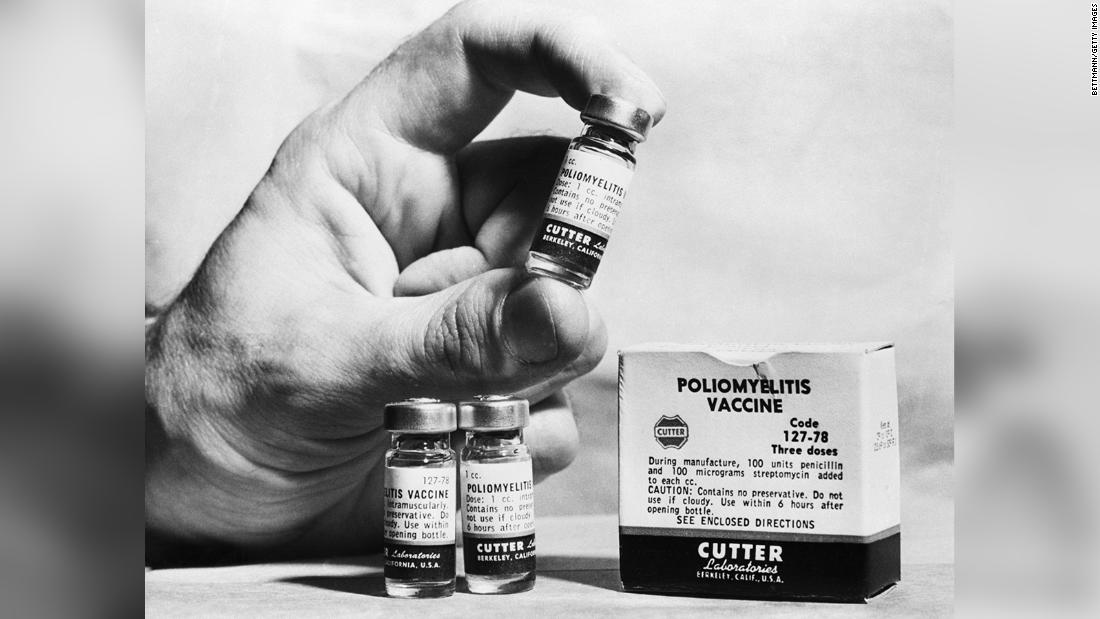

The Cutter Incident

On April 12, 1955, the government announced the first vaccine to protect children against polio. In a matter of days, laboratories had produced thousands of batches of the vaccine. Batches made by a company, Cutter Labs, accidentally contained live polio virus and caused an outbreak.

More than 200,000 children received the polio vaccine, but within days the government had to abandon the program.

“Forty thousand children contracted polio. Some had low levels, a couple hundred were left paralyzed, and about 10 died,” said Dr. Howard Markel, pediatrician, distinguished professor and director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan . The government suspended the vaccination program until it could determine what went wrong.

Monkey problems

However, further monitoring failed to uncover another problem with the polio vaccine.

“The way they would develop the virus was in the tissues of monkeys. These rhesus macaques were imported from India, tens of thousands of them,” said medical anthropologist S. Lochlann Jain. “They were caged by gangs and in those conditions, those who did not die on the trip, many got sick and the viruses spread rapidly,” added Jain, who taught a course in vaccine history at Stanford and is working on a publication. about the incident. The scientists mistakenly thought that the formaldehyde they used would kill the virus. “It was transferring millions of Americans,” Jain said.

No current vaccine contains the SV40 virus, the CDC says, and there is no evidence that the contamination has harmed anyone.

The epidemic that never was

In 1976, scientists predicted a pandemic from a new strain of influenza called swine flu. More than 40 years later, some historians call it a “flu epidemic that never existed.”

“Basically, his advisers told President Ford that we have a pandemic flu called swine flu that can be as serious as the Spanish flu,” said Michael Kinch, professor of radiation oncology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. . His latest book, “Between Hope and Fear,” explores the history of vaccines.

“Ford was being coaxed into coming up with a vaccine that was hastily prepared. When you have a new strain situation like that, they had to do it on the fly,” Kinch said.

Ford made the decision to make vaccination mandatory.

The government launched the program in about seven months and 40 million people were vaccinated against swine flu, according to the CDC. That vaccination campaign was later linked to cases of a neurological disorder called Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can develop after infection or, in rare cases, after vaccination with a live vaccine.

“It was kind of a fiasco,” Markel said. “The good news is that there was never a swine flu epidemic. So we were safe, but that shows you what could happen.”

Growing mistrust in the US

It took several incidents for people to begin to distrust vaccines. Even after thousands of children were sickened by the first polio vaccine in 1955, when the program was restarted, parents made sure their children were vaccinated. They had clear memories of the epidemics that paralyzed between 13,000 and 20,000 children each year. Some were so deeply paralyzed that they couldn’t even breathe easily on their own and relied on machines called iron lungs to help them breathe.

“Parents were pushing their children to come to the head of the line to get the polio vaccine, because they had seen epidemics every summer for years, and they saw children with iron lungs and they were terrified,” he said. Markel.

Markel said that people’s attitudes began to change between 1955 and the troubled swine flu vaccination project of 1976.

“You have civil rights, when people see the police beating people on television. You have the Vietnam war, where people start to be disgusted with the assassination. You have Watergate when the president is literally lying through his teeth,” Markel said. . “That led to real mistrust of authorities and the federal government, and it spread to doctors and scientists. And that only progressed over time.”

A ‘colossally stupid’ move

Markel said people’s mistrust of the system prompts the idea of the FDA rushing this process before late-stage clinical trials are completed. “colossally stupid.”

“This is one of the most ridiculous things I have ever heard from this administration,” Markel said. “All it takes is one bad side effect to basically screw up a desperately needed vaccine program against this virus. It’s a recipe for disaster.”

FDA Commissioner Hahn said the decision on the vaccine will be based on data, not policy, but Kinch shares Markel’s concern.

“This could cause substantial damage,” Kinch said. Kinch, who is a patient in one of the vaccine trials, said that the clinical trial process must be followed to the end. A USA too early for a vaccine could cause a “nightmare scenario” for several reasons.

One, the vaccine may not be safe. Two, if it’s not safe, people will lose faith in vaccines. Three, if a vaccine does not offer complete protection, people will have a false sense of security and increase their risk. Four, if a lower-quality vaccine gets an EUA, a better vaccine may never get approved, because people would be reluctant to enroll in trials and risk receiving a placebo instead of a vaccine.

“People are going to die needlessly if we take a chance on this,” Kinch said. “We have to do this right.”