[ad_1]

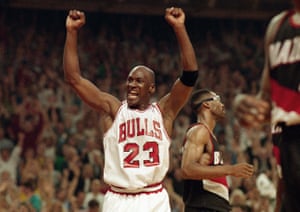

HHave we never seen Michael Jordan like this before, or is it just that we forgot him? Anyone who has experienced the Chicago Bulls’ dominance over the NBA during the 1990s, including, as me, as a child, can probably still recall the broad contours of Jordan’s talent, the qualities that made him such an exceptional athlete : elasticity; hanging time; the spectacular mattes, the absurd hand change arrangements and the clutch buzzers; Gross power. Jordan reigned in “the end of the story”, in that curious decade between the fall of the Berlin Wall and September 11, and despite his ability with a ball in his hand, he always seemed a little remote, a little above of everything. He was the perfect athlete, in a sense, during the post-political decade. In an era that he thought had solved everything, Jordan was the player he really had.

And yet. As The Last Dance, the 10-part documentary whose first episodes premiered on ESPN in the US, shows. USA Sunday (with worldwide releases for each on Netflix the next day), it was so much more. Yes, Jordan was gloriously, ironically male. Yes, his body functioned like a Swiss Army knife, the limbs slicing through the air in all directions at one moment and then re-forming a streamlined cylinder the next. Yes, he was capable of scandalous things on the court. But he was also a bully, a wrecking ball, the owner of a volcanic will to win, a man of almost unbearable intensity. As much as Jordan has provided millions over his career, and he will surely give millions more with the launch of this documentary banquet, it is difficult to escape the feeling of being him: occupying that body, taking advantage of that talent, channeling That relentless drive to be the best must have been incredibly difficult. The Last Dance is nominally about Jordan’s last season with the Bulls, but the flashbacks give us the full and luxurious story of His Airness, and what it really offers us at the end of it all is a sympathy study. The man who emerges from these 10 hours of pure 90s nostalgia is heroic, absurd, demanding, difficult, and sometimes downright tyrannical, and somehow even more attractive to all his flaws. He cared about one thing, and only one: win. Once you understand the uniqueness of Jordan’s approach, everything else about him makes sense.

The Last Dance takes its title from the name of the dossier that Bulls coach Phil Jackson, in typically cunning marketing, delivered to each player prior to the 1997-98 season. Jordan had progressed from a promising but impolite No. 3 pick in the 1984 draft to the NBA’s first authentic international superstar; His rise was parallel, or rather driven, to the league’s overall rise. But by 1997, five titles for good, it had become clear that the Jordanian Bulls had only one season left. Veteran general manager Jerry Krause had signaled that the Chicago team of champions would disband at the end of the season. Jackson, the man who convinced Jordan in the late 1980s to put his ego aside and trust in the transformative beauty of the triangular offensive, was also to be shown the door. We all know how the story ends: Jordan led the Bulls into a second round of three mobs, before departing for sunset, but what happens along the way is all the joy of this show. A television team followed the Bulls throughout the season, and the footage they recorded, footage that has never been broadcast until now, forms the backbone of The Last Dance. We see Jordan dealing with Scottie Pippen’s back injury (the Bulls lieutenant ended up out of action for the first 35 games of the season) and continued discord between Pippen and management. We see him trying to keep the playgroup together during the periodically disappearances and brain faints of a pleasantly insane Dennis Rodman. We see him arguing with Steve Kerr, of all people.

But above all, we see Michael Jordan angry. If there’s one theme that comes out most emphatically from The Last Dance, it’s the sheer force of Jordan’s personality, the anger that propelled him. Repeatedly throughout his career, Jordan used snubs against his greatness as motivation to erase everything in front of him. He decided to destroy the Portland Trail Blazers in the 1992 final because he didn’t like the comparisons that suggested that he and Clyde Drexler were on the same level. He and Pippen decided to join Toni Kukoc in the first game the Dream Team played against Croatia at the 1992 Olympics because Krause, a regular punching bag, thought Kukoc was a good player who would improve the Bulls roster. He punched Kerr in the face in the preseason before the 1995-96 campaign, before his first comeback season after 18 months of playing baseball, because “we were screwed up when I came back” and a point had to be made.

To see Jordan reflect on these incidents now, settled in the armchair of his spacious beach house, accommodated in a middle age, with a cocktail glass beside him, laughing fondly as the filmmakers hand him a tablet and he looks at the images. For example: from Gary Payton reflecting on his efforts to stop Jordan in the 1996 finals, it may all seem a bit ridiculous that he ever took things so seriously.

But if The Last Dance proves that Jordan wasn’t exactly popular with his teammates, it also reminds us how magnetic his personality was, how charismatic and fun he could be, from the cult that quickly grew around him. We repeatedly see him goofing around in practice, joking around with the press, or in the Bulls’ private jet, with the cigar in his mouth (the large amount of tobacco smoked during The Last Dance would be enough to cause lung cancer. to most people), gently teasing his entourage. The respect of his rivals is unmistakable. In the summer of 1995, as he was preparing for his first full season after retirement, Jordan was hired to shoot Space Jam. He asked Warner Brothers to build him a practice facility during filming, and the studio duly complied by creating the Jordan Dome, a full-size basketball court, and a training gym. From 7am to 7pm, Jordan filmed the movie. Then, for three hours after the shooting wrapped up each night, he played pickup games with a list of the NBA’s best, all of whom traveled to Los Angeles to be near him: Patrick Ewing, Reggie Miller, Dennis Rodman. “Those were the best games,” recalls Miller with youthful awe.

The series sensitively addresses the murder of Jordan’s father and the other, darker chapters of his career: his gambling habit and lack of commitment to popular politics. Jordan’s apolitical character: “Republicans also buy sneakers,” he reportedly said after refusing to endorse North Carolina Democrat Harvey Gantt in his 1990 Senate race against the notorious racist Jesse Helms. James deserves the title of best basketball player in history. When LeBron is fully committed to his role as a public figure and not afraid to take polarizing stances on political issues, Jordan mostly avoided anything that would alienate segments of his huge bipartisan fan base. The Last Dance does not avoid putting pressure on Jordan on these issues, although his responses are mostly unsatisfactory; He says he couldn’t endorse Gantt because “he didn’t know the guy.”

It is clear that his priorities are elsewhere: making money, gambling (how strange is the moral panic of that time about Jordan’s love for a bet today) and, above all, winning. That focus on making money and talking everything on the court, which, according to the evidence here, his teammates evidently shared, made Jordan the archetype of the modern athlete. Jordan was not so much an individual as an industry, and set the template for the generations of athletic gods that followed: endorsements, clothing lines, cultural ties, and carefully managed media ads. But the healing of his image was designed, very obviously for Jordan’s mind, in pursuit of a single goal: to be the best. Winning was the real goal, and everything else had to serve him. If Jordan had any politics, any awareness of racial or economic injustice, he sublimated himself into the overwhelming fury that consumed him the moment he stepped on the court.

The most poignant scenes in The Last Dance show Jordan in the moments after his first and fourth titles. In 1991 we see him in the dressing room with his father, his face pressed towards the Larry O’Brien trophy, crying a stream of tears, and for a second we are there with him, living the extraordinary catharsis of that first ring. In 1996, his first comeback title after an 18-month hiatus in baseball, he is back in the locker room, grabbing a ball, facedown on the ground, his body convulsing as tears flow unhindered once again. These are the only moments in the documentary where we see Jordan from the 1990s in any way other than the training ground talker, the destroyer on the court, the GOAT chewing cigarettes; the only time he is not a braggart with his legs. It is fitting that the athlete perhaps best known in popular culture today for the “crying Jordan” meme be reintroduced to us in this way. Myths and misperceptions revolved around Jordan throughout his career: that he was selfish, he was not a team player, he was only concerned with getting rich. To see the images of him after those 1991 and 1996 titles, that Ferrari with a body full of uncontrollable tears, possessed by the launch of victory, is to understand who Michael Jordan really was: an animal as competitive as professional sport has seen .