[ad_1]

As large parts of the world prepare for a second wave of coronavirus cases, governments have pinned their hopes on the rapid development of a vaccine that provides a route out of the pandemic.

Pharmaceutical companies have moved with unprecedented speed and tens of thousands of people in more than a dozen countries, from Brazil to Saudi Arabia, have volunteered for human trials.

If vaccines work, as early tests suggest, it will push the button for immediate mass production at a scale and speed never seen before. But the recent setbacks of at least one leading manufacturer have shown that the path to a proven and widely available outlet may not be straightforward.

In total, there are more than 300 candidate vaccines, according to the World Health Organization – about 40 are being tested in humans, and only nine of these have reached the final stage before possible implementation: phase 3 trials.

AstraZeneca at the University of Oxford is developing one of nine vaccines in the UK; two of the most advanced US candidates come from the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, in association with BioNTech of Germany and Moderna; Sinovac Biotech, CanSino Biologics and Sinopharm are producing four vaccines in China, which has two different injections in development; and one is run by the US multinational Johnson & Johnson. A Russian vaccine produced by the Gamaleya Research Institute entered phase 3 this month. All nine have already signed purchase agreements with governments around the world.

How will the different vaccines work?

All possible vaccines broadly follow the same logic. They deliver a protein to the body that attaches to a part of the coronavirus, called a spike, and activates the immune system to produce antibodies and cells that fight viruses to defend against infection.

There are dozens of possible ways to transmit immunizing proteins to the body, and researchers around the world are testing different approaches.

Three of the Chinese phase 3 candidates use an inactivated virus as a vector. In other words, Sars-Cov-2, which has been destroyed by heat or chemicals. In theory, it will elicit the correct immune response, but without any of the serious health effects of the live virus.

AstraZeneca, J&J, China’s CanSino, and Russia’s Gamaleya Research Institute use an adenovirus, a common virus that causes coughing and fever, that acts like a hooded horseman, carrying immunizing protein into battle.

Moderna and Pfizer / BioNTech are developing RNA-based vaccines, which use specific parts of the genetic code of the Sars-Cov-2 virus to trigger the immune response.

How are the essays structured?

All phase 3 vaccine trials are so-called “event-based”, which means that the trial only ends when a certain number of people in the vaccinated group and in the control group, receiving a placebo, have contracted the virus and have shown symptoms. Moderna, for example, has set the number of these “positive events” at 151. It also means that the more prevalent the disease is in the population at the time of the trial, the faster it will be to get results.

Although a vaccine is commonly expected to completely prevent people from becoming infected, this result is rare and has never been achieved for other coronaviruses or influenza strains. Instead, a more pragmatic goal, embraced by most vaccine developers, is prevention of symptomatic Covid-19 infections. That’s the stated goal of the AstraZeneca, Moderna, Pfizer / BioNTech, and J&J vaccines.

“What we really want from a vaccine is to prevent people from going into hospital, going into intensive care and dying,” said Andrew Pollard, who leads the AstraZeneca trials at the University of Oxford. “It’s likely a much bigger hurdle to completely prevent an asymptomatic infection.”

Immunity, boosters and side effects

Given the growing chorus of experts warning that the vaccine is likely to confer only temporary immunity, the ability to “boost” the immune response at a later date with another injection is important.

“The assumption at this point is that we will shoot for one year immunity,” said Kate Bingham, chair of the UK government’s Vaccine Task Force. Seven of the candidate vaccines in phase 3 are designed to be given in two doses, to increase the chances that they will elicit an effective immune response. Only J&J and CanSino are testing single dose injections.

“Even if you have a vaccine with a second dose, you may need to increase it every year,” Ms Bingham said.

AstraZeneca, CanSino, J&J and the Gamaleya Research Institute use a non-replicating viral vector, in this case an adenovirus, to deliver the vaccine to the recipient. These are infamously difficult to stimulate because the body learns to mount an immune response to the adenovirus and is therefore prepared to fight it quickly next time.

“It’s a potential hurdle in terms of a long-term revenue stream, but one of the other vaccines could be your booster option,” said Matthew Harrison, a biotech analyst at Morgan Stanley.

Raque Ataide, a 30-year-old gynecologist living in Sao Paulo, volunteered for the AstraZeneca trial in Brazil: “I haven’t touched my mother or father since March. . . and if I am protected, I feel that I am protecting them. It is a personal matter and a professional obligation ‘

Carol Kelly, an Atlanta nutritionist, responded to a Moderna ad for test volunteers ages 55-65: ‘It’s a little thing I thought I could do, because so many people around the world have suffered.’

Side effects are also being closely watched. Early trials of the Moderna vaccine, for example, when participants were given a dose more than double the current dose, resulted in 20 percent experiencing significant adverse effects, including headaches and fever.

AstraZeneca has had to pause trials twice after participants became seriously ill, and although work was resumed in the UK and elsewhere, research remains on hold in the US.

Which countries have bought doses so far?

Despite global calls from the WHO for countries to seek multilateral agreements that provide for equitable distribution of doses, the trials have sparked a surge of billions of dollars in vaccine negotiation by national governments.

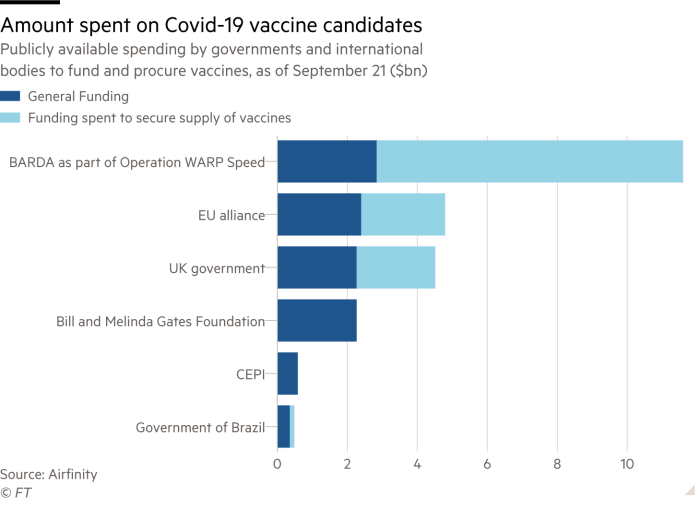

The US government’s Advanced Biomedical Research and Development Authority is the highest spender so far, having distributed more than $ 10 billion in funding to vaccine candidates, either through direct funding or through procurement agreements. of vaccines.

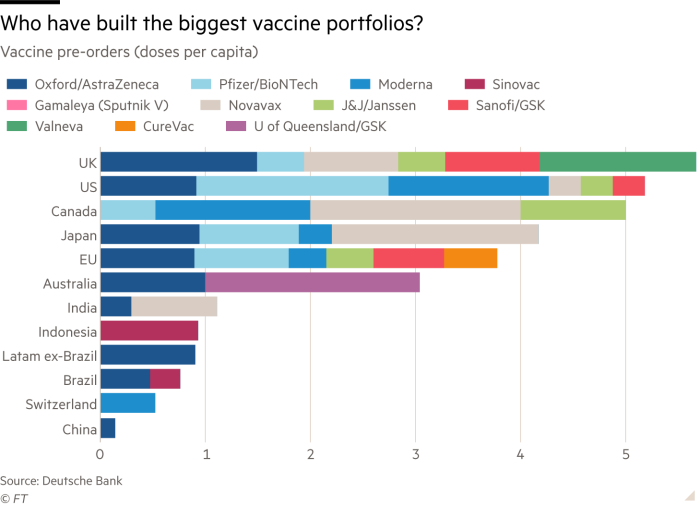

On a per capita basis, the UK has created the largest and most diversified vaccine portfolio, according to Deutsche Bank data, having pre-ordered more than five doses per citizen spread across six leading vaccine candidates. The UK is closely followed by the US, Canada and Japan.

In total, the negotiation of the US, UK, EU, Japan and other rich nations has meant that rich countries that make up only 13 percent of the world’s population have bought more than half of the doses. fiancées of leading vaccine candidates, according to Oxfam, the charity. .

Covax, the global vaccine procurement facility, designed to ensure equitable distribution of doses, this week alone secured participation from 64 higher-income countries. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, one of the founders of the facility, has invested up to $ 895 million in nine Covid-19 vaccine candidates to be distributed under the program.

When can we expect results?

Scientists’ predictions for when the first vaccine could show positive phase 3 test results range from October this year, at the most optimistic time, to mid-2021 at the most pessimistic time.

Pfizer / BioNTech have said they would have enough data from their phase 3 trial to begin analysis in late October. Moderna, which has enrolled more than 25,000 participants in its trial and administered more than 10,000 of those two doses over the course of the vaccine, said last week that an interim analysis of the trial results is more likely to begin in November. and possibly until December.

When the AstraZeneca trial was restarted in the UK in September, the company said it was still on track to submit its vaccine for regulatory approval before the end of the year. Some 18,000 people in the UK, the US, South Africa and Brazil have received their AZD1222 vaccine as part of the trial so far.

Once the results of the initial phase 3 trial are available, the relevant national regulator could approve a successful vaccine within a month, the analysts estimate, allowing early administration of the vaccine to vulnerable groups. It is likely that it will take another six months to collect and analyze all the data from the phase 3 trial before the injection can be made available for larger public vaccination campaigns.

Additional information from Hannah Kuchler in New York, Clive Cookson in London and Carolina Pulice in Sao Paulo