[ad_1]

VOLATILE REGION. A Chinese militia ship identified by the Philippine Coast Guard during a patrol at Scarborough Shoal. File photo courtesy of the Philippine Coast Guard

MANILA, Philippines – As the world struggles to beat the coronavirus pandemic, China has remained as aggressive as ever in the South China Sea, including the part that Filipinos call the West Philippine Sea.

Tracking ships from other countries, ramming a fishing boat, and challenging a Philippine naval vessel patrolling its own territory are not new actions by China in contested waters. (LIST: China’s incursions into Philippine waters)

What makes these actions more marked is that they have continued amid the coronavirus crisis, which originated in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

“Now I think people are more scandalized. They assumed that in the midst of a global pandemic, there would be a calm [of Chinese activities in the South China Sea], and that has not happened, “Asia Maritime Analyst and Director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) Greg Poling said in a virtual forum in mid-April.

China even stepped up the ante when it created bureaucracies to administer the Paracel and Spratly island groups as if they were part of its Hainan province. He then named several dozen geographic features in these areas, as if he owned them.

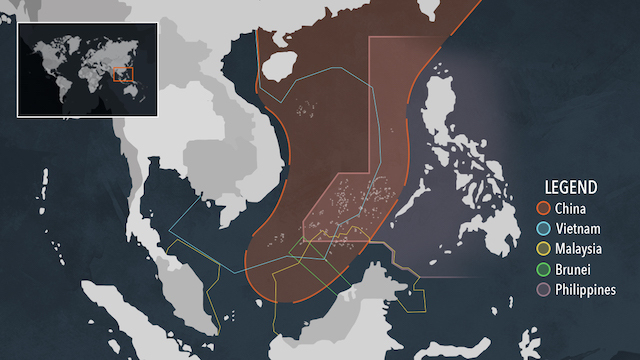

LINE 9 DASH. The orange part on this map shows China’s expansive claim to the South China Sea using its 9-stroke line, nullified as invalid by a 2016 international ruling.

These movements have sparked opposition from other claimant states in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines. At a time when governments are struggling to contain a deadly outbreak, China is pursuing its expansionist plans simply because it has the strength to continue to do so.

China’s aggressive movements in the South China Sea have affected almost all of the claimant states since the coronavirus pandemic spread beyond their own borders in early 2020. Here’s how:

MALAYSIA

Reuters He reported that China’s survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 entered waters near Malaysia on April 16, citing data from the ship tracking website Marine Traffic. The next day, the ship was seen near the West Capella oil exploration vessel operated by the Malaysian oil company, Petronas.

SURVEY VESSEL. Haiyang Dizhi 8 at sea. Weibo photo

The report quoted a Malaysian security source as saying that the Haiyang Dizhi 8 was flanked “at one point … by more than 10 Chinese ships, including those belonging to the maritime militia and the [China] Coast Guard. “A Vietnamese ship was reportedly also seen.

China denied this and said Haiyang Dizhi 8 was doing “normal activities”.

The Malaysian Foreign Ministry did not immediately report the incident, but days later, on April 23, the country’s foreign minister. Hishammuddin Hussein He called for disputes on the strategic waterway to be resolved “peacefully.”

The incident prompted the United States to mention what it described as China’s “intimidating behavior” in the maritime area. The United States rebuked China for taking advantage of other countries’ focus on the coronavirus pandemic to assert its expansive claims in the strategic sea.

Days after Haiyang Dizhi 8 was seen in waters claimed by Malaysia, Vietnam and China, the USS America and USS Bunker Hill, were seen near the area where the confrontation took place. The United States Indo-Pacific Command said warships were in the area as part of freedom of navigation operations.

VIETNAM

Sinking fishing vessel near Paracels

On April 2, a Chinese ship allegedly hit and sank A Vietnamese fishing boat with 8 people on board near the Paracel Islands. A local official in the Vietnamese province of Quang Ngai, near Paracels, claimed that the Chinese crew “captured and detained” the crew of the Vietnam fishing vessel on a nearby island.

STRESS IN THE SEA. Chinese Coast Guard vessel 4301 was involved in the sinking of a Vietnamese fishing vessel. Weibo photo

Beijing disproved The claim and responded with a different narrative: The Vietnamese fishing boat refused to leave the area after a China Coast Guard boat ordered it. The Vietnamese ship later “suddenly turned sharply” and hit the Chinese ship, which had tried to “avoid it.”

Vietnam rejected China’s claim and filed a diplomatic protest against the country.

The sinking of one of its fishing vessels, Vietnam said, violated the country’s sovereignty and “threatened life and damaged the property and legitimate interests of Vietnamese fishermen.”

Philippines then expressed “deep concern “ about the incident, recalling a similar experience when a Chinese ship struck a Philippine ship and abandoned Filipino fishermen offshore at Recto Bank (Reed bank) in June 2019. Philippine fishermen on the Gem-Ver fishing boat were rescued by Vietnamese fishermen hours after his abandonment.

“Our own similar experience revealed how much trust in a friendship is lost because of it; and how much trust was created by Vietnam’s humanitarian act of directly saving the lives of our Filipino fishermen … We have not stopped and will not stop thanking Vietnam” . Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) said in a statement.

Saying that the recent sinking of a Vietnamese ship incident undermines confidence in the region, the Philippines urged China and other Southeast Asian countries to foster cooperation during the coronavirus pandemic.

Haiyang Dizhi 8 returns to Vietnam waters

However, a A few days after the sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat near Paracels, China Haiyang Dizhi 8 research vessel returned to the waters of Vietnam in mid-April.

Maritime traffic data showed that the Haiyang Dizhi 8 was discovered to be 200 nautical miles off the coast of Vietnam, or within its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). He was also reportedly flanked by at least one China Coast Guard ship and other escort ships.

Haiyang Dizhi 8 was the same ship involved in a Deadpoint with Vietnam in 2019, when he spent weeks in waters near an oil rig in a Vietnamese oil block, operated by Russia’s Rosneft.

The ship reportedly conducted suspicious oil exploration studies in the Vietnam EEZ again, leading to tensions to get up once more between Hanoi and Beijing.

PHILIPPINES

The swarm near the island of Pag-asa

Pag-asa Island, known internationally as Thitu Island, is located 480 kilometers west of Puerto Princesa, Palawan. It is home to a Philippine community, with around 200 civilians and 50 military soldiers.

It is the largest of the 9 islets and reefs that make up the Kalayaan Group of Islands (KIG), the portion of Spratlys claimed by the Philippines. As a municipality, the KIG is governed from the island of Pag-asa.

The 37-hectare island has the country’s only KIG airstrip. However, this track is not paved and some parts are in poor condition, making it difficult to schedule flights to the island.

So in late 2018, the government started building a beach ramp in Pag-asa, so that building materials can be brought in to fix and pave the runway.

In December 2018, AMTI of the Washington-based think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) began monitoring the presence of assembled Chinese fishing vessels near Pag-asa Island.

CHINESE SHIPS. Dozens of Chinese ships are seen near Pag-asa Island (Thitu Island) after the Philippines begins building there. Photo courtesy of CSIS / AMTI / DigitalGlobe

These fishing vessels are widely believed to be militias, a paramilitary fleet that serves China’s expansionist purposes without provoking open conflict with other demanding states.

The Philippine government previously protested the Pag-asa swarm in the summer of 2019, but it has persisted since the pandemic began.

In January and February 2020, the Philippine Armed Forces (AFP) spotted a total of 136 Chinese ships in the waters of Pag-asa. On February 17, the military counted 76 of them, the highest number in a single day during that period.

AMTI’s Poling said in a study in March that the swarm of the Chinese militia may have been sparked by the Philippine movement to improve structures on Pag-asa Island. Chinese ships may have intended to hinder Philippine ships approaching the island.

Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana denied this, saying that it was the erratic weather in the area, not the presence of Chinese vessels, that delayed and prolonged work on the island.

But even Philippine officials expect Chinese ships to remain in the area indefinitely.

From the watchtower in Pag-asa, the tops of the buildings at Zamora Reef, internationally known as Subi Reef, one of China’s 7 man-made islands in the Western Philippine Sea, could be seen on the southwest horizon.

Now transformed into a military base, Zamora Reef allows China to keep the fleet of vessels seen near Pag-asa Island, just 14 nautical miles away, national security adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr said in early March.

ENHANCE. This June 2019 satellite image shows construction work on the island of Pag-asa, the main Philippine outpost in the Western Philippine Sea. AMTI-CSIS photo

Corvette

On February 17, the Philippine Army’s most powerful commissioned vessel, BRP corvette Conrado Yap, was on her third day of territorial patrols covering the KIG and Malampaya Natural Gas Facility off Palawan when she encountered a vessel of foreign war patrolling the same waters.

Sailors at Conrad Yap identified the other vessel as a corvette of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLAN) with bow number 514.

Conrad Yap issued a radio warning to inform the other corvette that it was invading Philippine waters. PLAN 514 responded by radio: “The Chinese government has immutable sovereignty over the South China Sea, its islands, and its adjacent waters.”

BRP CONRADO YAP. Spectators raise their flags during the arrival of BRP Conrado Yap (PS 39) at Pier 13 in Manila in August 2019. File photo by KD Madrilejos / Rappler

Philippine sailors reiterated their challenge to the Chinese intruders and told them to “proceed directly” to their next destination. The Chinese sailors also repeated their claim that they were in Chinese waters and maintained the speed and course of their ship.

At this point, Philippine sailors noted that PLAN 514 the director of arms control was directed at Conrad Yap. The commander of the Philippine Armed Forces in Palawan, Vice Admiral René Medina, said this meant that the Chinese warship had locked its weapons in Conrad Yap as a potential target, “ready to fire in a second.”

The incident did not escalate, and both warships continued on their way. However, the act of targeting the Conrad Yap was, by international military conventions, an act of aggression.

“This hostile act by the Chinese government and the invasion into the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone is perceived as a clear violation of international law and Philippine sovereignty,” said Medina.

One of the staunch defenders of the Western Philippine Sea, retired Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Antonio Carpio called the incident “pure and simple harassment” by China. Meanwhile, maritime law expert Jay Batongbacal viewed the incident as a “provocative and reckless escalation” of tensions in the Western Philippine Sea.

The DFA officially protested this incident with the Chinese embassy in Manila on April 22.

Activity on recovered reefs

In late March, Chinese state media reported that the Chinese Academy of Sciences had launched new research centers at Zamora Reef and Kagitingan Reef, known internationally as Fiery Cross Reef.

New research centers on the two recovered reefs complement the previously built station at Panganiban Reef, known internationally as the Mischief Reef. Together, they form an “integrated scientific research base” for China in the Western Philippine Sea.

KAGITINGAN REEF. This satellite image dated January 1, 2018 shows the Kagitingan Reef (Fiery Cross Reef) in the Western Philippine Sea (South China Sea). Photo courtesy of CSIS / AMTI / DigitalGlobe

The research stations have “several laboratories of ecology, geology and environments, [and] it can support scientists in field research, sampling and scientific research “in the area,” the Xinhua report said.

Poling said these are new research units, not necessarily new facilities or structures on the recovered islands. However, they show that China remains undeterred to increase its presence and control in the West Philippine Sea.

On March 28, the Israel-based satellite imaging company ImageSat reported seeing a Chinese army Shaanxi Y-8 transport plane on the Kagitingan reef.

The “routine operation” of deploying military aircraft on the recovered islands could indicate that the Chinese military is “barely affected” by the coronavirus pandemic.

SOUTH CHINA SEA

China names two new districts and 80 maritime features

On April 18, China announced that it created two new districts in the South China Sea: the Paracel (Xisha) island group district near Vietnam and the Spratly Island group district (Nansha), part of which is located in the Western Philippine Sea.

PARACEL ISLANDS. An aerial view of the Qilianyu islands in the Paracel chain, which China considers to be part of Hainan province on August 10, 2018. AFP file photo

Beijing placed the districts under the control of the Chinese city of Sansha in Hainan province and named Woody Island (Yongxing Island) as the administrative base of the Paracel Island district and Fiery Cross (Kagitingan Reef) as the administrative center of the Spratlys district.

A few days later, China followed this naming 80 islands, reefs, seamounts, schools and ridges, 55 of which were submerged in the water. The move was seen as a violation of international law and increased tensions with several plaintiff states, including the Philippines.

With the consecutive naming of districts and features, Beijing again sought to claim ownership of virtually the entire waterway, citing the areas as part of its territory.

Carpio said China’s naming of districts and characteristics does not equate to ownership, but cautioned that it could be another way for Beijing to assert its propaganda that it owns the South China Sea.

Both Vietnam and the Philippines quickly rebuked China’s actions and lodged diplomatic protests to express strong opposition to what they declared violated the sovereignty of their respective countries.

The DFA, in particular, said it did not recognize the Chinese city of Sansha, which includes the new districts of the South China Sea, nor the names given to some features in the KIG at Spratlys.

PAG-ASA ISLAND. An aerial view of the largest Philippine outpost in the Western Philippine Sea. Photo from the Center for Strategic and International Studies / Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

Since 2012, the Philippines has protested The “illegal establishment of the city of Sansha” in China and rejected its claim that the jurisdiction of the city extended to the territory and sea areas in the West Philippine Sea.

Foreign secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr He had also previously said that China had erroneously declared KIG and Masinloc Bas (Scarborough Shoal) as part of Chinese territory.

At 5:17 p.m. Today, the Chinese embassy received 2 diplomatic protests: 1. Aiming a radar gun at a Philippine Navy ship in PH waters and 2. Declaring parts of Philippine territory as part of Hainan province, both violations of the international law AND Philippine sovereignty.

– Teddy Locsin Jr. (@teddyboylocsin) April 22, 2020

“The establishment and alleged extension of the jurisdiction of the ‘Sansha City’ of which the two new districts are a part, violates the territorial sovereignty of the Philippines over the Kalayaan Island Group and Lower Masinloc, and infringes on sovereign rights of the Philippines on the waters and the continental shelf in the West Philippine Sea, “said the DFA.

By objecting to China’s claims, the Philippines asserted its 2016 victory against China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

“The unanimous Award issued by the Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in arbitration instituted by the Philippines, has comprehensively addressed China’s excessive claims and illegal actions in the South China Sea. ” DFA said.

The international arbitration award, downplayed by President Rodrigo Duterte and rejected by Beijing, affirmed the sovereign rights of the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea. The landmark ruling also denied the spurious claim of China’s 9-dash line that it used to claim virtually across the entire waterway.

get together

What recourse do the complaining States of Southeast Asia have to the aggression of Beijing in the strategic maritime region? China rejects the arbitration award, and the Philippine government, under Duterte, has almost given up trying to make Beijing yield.

The best chance to go back, Carpio said earlier, would be to go back together.

Individually, these smaller states cannot match China’s naval presence, but if they unite to joint maritime patrolsThey should somehow be able to affirm their presence in the water, Carpio suggested.

Joint patrols. A Philippine Navy contingent joins the Rim of the Pacific Exercise in Hawaii in June 2018. File photo of the Philippine Office of Naval Public Affairs

However, Esperon rejected Carpio’s suggestion, saying that the naval patrols that could provoke China were out of the question.

Regarding the naming characteristics of China in the Western Philippine Sea, Carpio said the Philippines could simply authorize the National Authority for Mapping and Resource Information as the national authority that approves names. In this way, international organizations that approve names of geographical characteristics should block the applications of names of China.

Carpio had been suggesting this to the government since 2018, but to no avail.

“The Chinese plan does not have to happen, it does not have to be carried out if we go back. We can stop it if we want to stop it. But if we do nothing, then they will be successful,” Carpio warned. .

Meanwhile, the Duterte administration has stuck to its mantra that China is its best friend, even in the midst of a pandemic. Despite the incidents at sea, the President never condemned or called China, but thanked Chinese President Xi Jinping on several occasions.

Is it any wonder, then, that everything remains the same for China in the Western Philippine Sea? – Rappler.com

[ad_2]