[ad_1]

When AstraZeneca confirmed Tuesday night that it had temporarily halted trials of its coronavirus vaccine, the news puzzled millions of people around the world who were counting on a puncture as a route back to normal life.

The drug group’s measured statement sought to dispel any suggestion that the race to develop a vaccine – the candidate it is developing in association with the University of Oxford is seen as a pioneer – had encountered major problems.

AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot called the decision proof of his company’s commitment to “science, security and the interests of society.” The hiatus showed the company would follow those principles, he said, as a committee of independent experts assessed a suspected serious adverse reaction suffered by a UK trial participant.

But the incident has served as a reminder that the pharmaceutical industry is trying to accomplish an unprecedented feat: aiming to outperform the earlier, faster development of a vaccine by several years. At the moment, that record is held by the mumps vaccine, which took four years to commercialize.

Despite the anticipation of a vaccine that will arrive and free people from lockdown, history shows that there are no guarantees. Overall, infectious disease vaccines have a success rate of about 33.4 percent after entering human trials, although this rises to 85 percent for those that make it to phase 3 trials.

There has been an extraordinary scientific effort dedicated to finding a vaccine that will prevent Covid-19 or at least decrease symptoms. The Oxford-AstraZeneca candidate is one of five in clinical trials using the weakened form of a common type of virus known as adenovirus. The modified adenovirus provides instructions for human cells to make proteins in Sars-Cov-2, the coronavirus that causes disease. This prepares the immune system to recognize and attack it.

Another type of vaccine uses RNA, a molecule that contains genetic instructions for making viral proteins that is inserted directly into human cells. Modern American biotechnology and the partnership between Pfizer and BioNTech are taking this approach for their vaccines and, together with the Oxford / AstraZeneca candidate, are considered among the most advanced.

The pause in the AstraZeneca trial comes as politicians have encouraged the narrative that a vaccine will arrive at “incredible speed,” to quote the name of US President Donald Trump’s vaccine project.

Earlier this week, Matt Hancock, the UK health secretary, was hopeful that the Oxford one might even get regulatory approval before the end of the year, although he suggested the early part of 2021 was more likely.

Some experts said the announcement of the hiatus will be a useful reality check, emphasizing that safety is paramount.

Referring to it at a Senate hearing on Wednesday, Francis Collins, director of the US National Institutes of Health, said: “When we say that we are going to focus on safety and we will not compromise, here is the proof. TO”.

If the trial participant’s illness turns out to be “a real consequence of this vaccine and it can be shown to be cause and effect, then all the doses that are currently being manufactured for that will be discarded. We don’t want to make something that is not safe, ”he said.

Dan Mahony, co-director of healthcare at fund manager Polar Capital, said the bar for administering a vaccine can be higher than for other pharmaceuticals because they are almost always given to people who are otherwise well.

The difficulty for vaccine manufacturers is that even clinical trials involving 30,000 people, such as AstraZeneca’s current Phase 3 trial, may not detect rare, but potentially devastating, reactions.

When a swine flu vaccine was widely distributed in 1976 at the urging of then-US President Gerald Ford, a small number of cases of a serious neurological disorder called Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) were found. The highest risk was about one additional case per 100,000 people who received the vaccine, but the program had to be stopped.

Mahony said regulators were always wary of one in 10,000 to 100,000 reactions that studies like AstraZeneca’s wouldn’t necessarily capture. She added: “These are large studies, but it is still difficult to detect those rare events. But one in 100,000 [adverse events] it is still quite important if up to a billion people are to be vaccinated. “

That possibility was behind AstraZeneca’s decision to voluntarily pause the trial, he said. “The concern on the minds of a regulator and a pharmaceutical company for any clinical trial is what about rare events that we would not have statistically detected?”

The scientists emphasized that pauses are a routine part of drug development and do not necessarily imply longer-term question marks about a drug’s efficacy and safety.

Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a London-based research charity, said: “It is very unusual to go through a vaccine test and not have to pause it.”

The condition that led to the trial pause is transverse myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord that has a known, but very rare, association with vaccination.

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, cautioned against assuming a link between the participant’s illness and the vaccine.

“When large numbers of people are included in trials, coincidental events can occur and when they are unexpected, an investigation is required to see if they are just a coincidence or a result of the vaccine,” he said.

Latest news on coronavirus

Follow FT’s live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

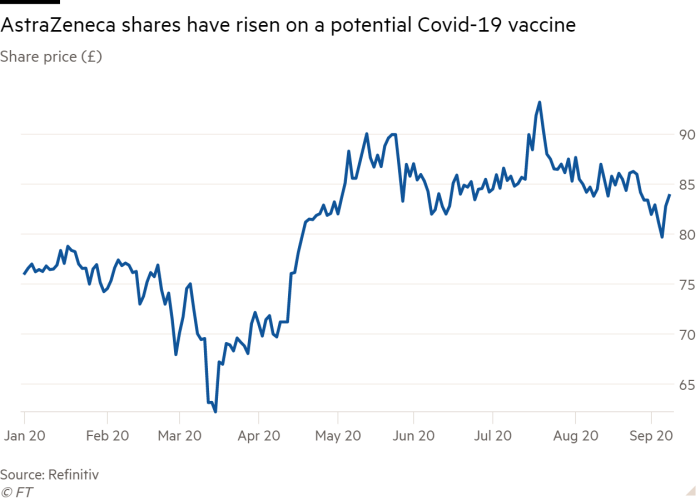

Analysts and investors reacted largely calmly to the news that the trial was being paused. Peter Welford of Jefferies said that temporary breaks were “standard practice in clinical trials.” He and his team anticipated “a short-term stock correction that may be misplaced,” he added.

Describing the quiet market reaction to the news (shares fractionally closed to almost £ 84) as “sensible”, Polar Capital’s Mahony argued that the fate of the vaccine is unrelated to the company’s broader prospects for success. AstraZeneca has pledged not to benefit from the drug during the course of the pandemic.

He said: “I don’t think this vaccine was a financial driver for them. It’s more of a factor in being a good corporate citizen. “

AstraZeneca’s status as one of the world’s fastest-growing pharmaceutical companies was due instead to its oncology business, Mahony said.

“This is a company on the rise and they have stepped in to do something at Covid from a position of strength.”