[ad_1]

China wants to beat the world in the race to find a coronavirus vaccine, and, by some measures, it is doing exactly that.

Desperate to protect his people and deflect mounting international criticism of how he handled the outbreak, he has cut red tape and offered resources to drug companies. Four Chinese companies have begun testing their candidate vaccines in humans, more than the United States and Britain combined.

But China’s leaders have fueled a vaccine industry that has long been embroiled in quality problems and scandals. Only two years ago, Chinese parents exploded in fury after discovering that ineffective vaccines had been administered primarily to babies.

Finding a vaccine is not enough. Chinese companies must also win the trust of the public, which may be more inclined to choose a foreign-made vaccine than a Chinese vaccine.

“The Chinese now have no confidence in vaccines produced in China,” said Ray Yip, former head of the Gates Foundation in China. “It’s probably the biggest headache. If they didn’t have all those incidents, people will probably line up for miles to get it.”

The need is urgent. More than 247,000 people have died worldwide, according to official figures as of Monday, and the actual count is probably much higher. The coronavirus remains stubbornly difficult to remove. Even China, which officially appears to have tamed the spread, has suffered sporadic outbreaks.

China also wants to deflect allegations that its silencing of early warnings contributed to the global pandemic. The development of a vaccine for the world would further enhance its position as a global scientific and medical power.

Therefore, China has made its vaccine a national priority, although it has not disclosed the details of the spending. A senior official said a vaccine for emergency use could be ready by September. State media have made Chen Wei, the top virologist in the Chinese military, who is leading one of the vaccine’s efforts, a celebrity. The public is responding.

Huang Shiyue, an 18-year-old first-year medical student in Wuhan, left her apartment on an early Sunday for the first time in three months to take a taxi to a wellness center an hour away. There, she offered her arm in the name of science.

But in an illustration of how difficult it will be to find safe and effective treatment, Huang became sick and sick.

“If I can help and benefit people with a little movement,” he said, “then I think this is a very valuable thing.”

China’s vaccination campaign has revealed Beijing’s considerable strengths and blatant weaknesses. With its firm hand on the levers of Chinese industry, Beijing can corner companies and scientists to achieve national goals.

At the same time, China’s vaccine companies have grown accustomed to a closed political system that has a history of covering up security scandals and protecting them from foreign competition. Few invest heavily in research and development, and have not discovered many products with global impact.

Instead, many invest more in sales and distribution, a large part of which includes managing relationships with local disease control centers. Experts say that creates incentives for corruption.

China’s regulators also tend to look the other way when it comes to state-owned companies, which account for about 40% of the vaccine industry. Many vaccine manufacturers operate with the expectation of impunity, knowing that even if defective products are found to have been produced, they are unlikely to be shut down.

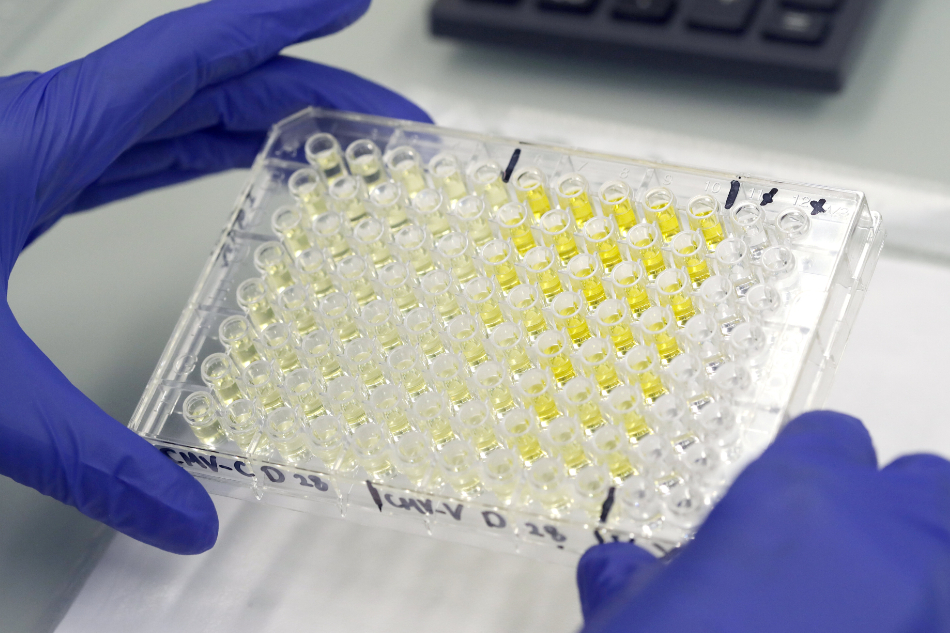

The vaccine Huang received is being developed by CanSino Biologics, a Tianjin-based pharmaceutical firm, and the medical science arm of the People’s Liberation Army. The CanSino vaccine was the first to enter phase two trials, which in the hierarchy of drug tests means that it is more advanced than the other candidates in the world, although there is no guarantee that it will be proven to be effective. (So far it has been tested in 508 people; a candidate from Oxford University in phase one trials, or tests in earlier stages, has been administered to twice as many people).

Another Chinese institution also has a candidate for phase two testing: the Wuhan Institute for Biological Products, an arm of the state-owned Sinopharm group. Sinovac Biotech, a private company, and the Beijing Institute for Biological Products, which also belongs to Sinopharm, have potential vaccines in phase one trials.

The Wuhan Institute was involved in a 2018 scandal in which defective vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, and other conditions were injected into hundreds of thousands of babies. China imposed a $ 1.3 billion fine on another virus maker involved, Changchun Changsheng. The scandal led to the firing of dozens of officials and promises of a speedy cleanup of the industry.

The government confiscated the “illegal income” from the Wuhan Institute, fined the company and punished nine executives.

The Wuhan Institute has been sued at least twice in China by plaintiffs who allege that the institute’s vaccines have caused “abnormal reactions,” according to court documents. In both cases, the court ruled that the Wuhan Institute had to partially compensate the victims with a total of approximately $ 71,500. Its executives have been accused at least three times of bribing officials at local disease control centers in various provinces to thank them for buying their vaccines. The executives were convicted, but no criminal charges were filed against the company.

Sinovac Biotech had also been involved in a bribery scandal, according to court documents. From 2002 to 2014, a court in Beijing said, the general manager of Sinovac Biotech gave the deputy director of China in charge of drug evaluations about $ 50,000 to help the company with drug approvals. Sinovac was not charged. The general manager was a man with the last name Yin, according to the documents. Chinese media reports have said that person is the current CEO, Yin Weidong, who held the title of general manager from 2001 to 2017.

Sinovac, the Wuhan Institute, and its parent, China National Biotec Group, did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite previous setbacks by companies, the Chinese government has given them permission to speed up trials. Regulators in the United States and elsewhere have done the same with other companies. The Wuhan Institute, Sinovac and the Beijing Institute obtained combined approvals to execute the first two phases, a decision questioned by several Chinese scientists, who considered that the safety results of the first phase should be evaluated before the second phase began.

Ding Sheng, dean of the Tsinghua University pharmacy school in Beijing, said that some companies were “adopting unconventional methods” in the preclinical research stage, executing tasks such as the animal design and modeling process at the same time as they had to be done consecutively, according to the People’s Daily, the official Communist Party newspaper.

“I understand people’s anxious expectations of a vaccine,” said Ding. “But from a scientific point of view, no matter how eager we are, we cannot lower our standards.”

He did not respond to a request for comment.

Chen’s academy issued Internet calls for phase one volunteers. Huang successfully registered for the second round on April 10. The next day, he received a call and a text message: Please come tomorrow.

“Of course, I was concerned at first,” she said. “Saying you’re not worried is impossible, right?”

She surfed the Internet and called her teacher, who listed the pros and cons. She sought the advice of her parents.

Then she was gone. The workers performed an antibody test to make sure she was not immune to the coronavirus, an HIV test, and a pregnancy test.

Participants were divided into low and medium dose groups and another placebo group, as part of a “double blind” experiment. Their group was not told.

Fifteen minutes after Huang received her injection, she began to feel dizzy. His stomach hurt. Her heart began to beat fast. She has diarrhea.

Chen and other doctors reviewed it. Someone offered him hot water. He took a walk in the sun. Finally, they took her by ambulance to a subway station, where she took a taxi home.

Huang said he feels good at home.

Shi Zibo, a third-year college student, also signed up to volunteer and received the vaccine on April 12. On the fourth day, she had a mild fever but said she had no other side effects.

“I was very proud when I got the call,” said Shi. “There are not many opportunities to contribute to other people in this life, so I will not regret it, regardless of the end result.”