[ad_1]

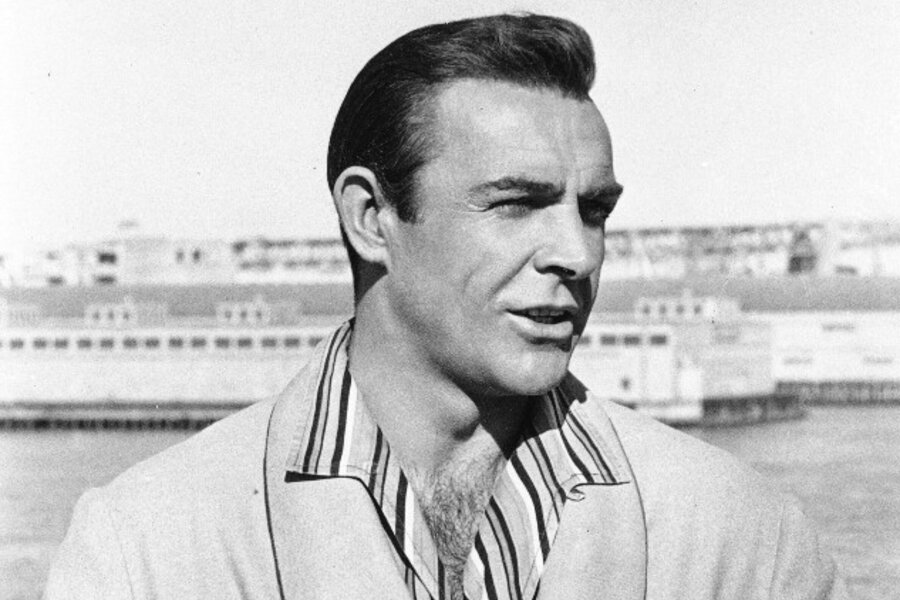

Writing a Sean Connery appreciation inevitably feels inadequate compared to experiencing reality. To get a glimpse of his magnetism, you can turn to a photograph of him in a tailored suit, leaning against an Aston Martin. You’ll probably get more of his menacing charisma by taking the “Chicago way” scene out of “The Untouchables.”

It might suffice simply to say: the king is dead.

As a lion of movies for half a century, Connery’s talent was on display. He was cast as James Bond without a screen test. It was that obvious. And since then, even in the minor films, Connery, who died on Saturday in the 90s, was never out of place on the screen. His presence was absolute. Noting his supreme confidence, the late film critic Pauline Kael once wrote, “I don’t know of a man since Cary Grant that men have wanted to be so much.”

As the most earthy and macho movie star ideal, Connery was so beloved that he was shared, like folklore, between generations. It helped that it never seemed to attract the audience, or anyone, for nothing. With arched eyebrows and mischievous banter, there was little that Connery (almost always the leader) didn’t master. And to some extent, that arrogance shaped his career as well.

Connery, 32 when “Dr. He did not “come out”, he had already lived through the Second World War. Born into poverty in Edinburgh, he dropped out of school at age 13 during the war and worked as a laborer and bricklayer before donning his tux. He also saw Bond as a product of the war.

“Bond appeared on the scene after the war, at a time when people were fed up with rationing and monotonous times and general purpose clothing and a predominantly gray color in life,” said Connery, who served in the British Navy. when he was a teenager, to Playboy in 1965. “This character arrives who goes through all that like a very hot knife in butter, with his clothes and his cars and his wine and his women.”

Long after achieving fame, Connery happily gave up. He spent his last two decades happily retired in the Caribbean, often playing golf with his wife, little impressed and little tempted by the more modern Hollywood productions. (He said he was “sick of the idiots”).

There was irony in that. Connery, like the original film Bond, did much to create the style and tone of today’s film franchises, even if few carry a hint of Connery’s danger. His Bond heir, Daniel Craig, credited Connery on Saturday with helping “create modern blockbuster.” It’s hard to imagine that the soft-spoken Secret Service spy would ever have become a cultural force if the franchise hadn’t traded in its star’s brutal charm early on. Connery crucially added humor to the pages of Ian Fleming, along with a dash of cruelty.

Connery’s Bond became an icon of its time, increasingly distant from today. It was the epitome of a macho, womanizing and handsome image that loomed over the second half of the 20th century. Connery differed from his character in many ways, but not all. In that same Playboy interview, he explained why he believed that hitting a woman with an open fist was justifiable.

Bond is the first word on Connery, but it certainly isn’t the last. Against fans’ pleas, he left the character at age 41 (he was later convinced to return for 1983’s “Never Say Never Again”), refusing to be typecast. His best and most interesting work came later.

“The Hill” (1965) was the first of five films with Sidney Lumet (the others were “The Anderson Tapes”, “The Offense”, “Murder on the Orient Express” and “Family Business”), and although it is seen less Like many of Connery’s, it remains arguably the best expression of the actor’s strong power. He plays a prisoner of indomitable strength and defiance imprisoned in a sadistic WWII British Army military prison in the scorching Libyan desert.

He was a soldier again a decade later in John Huston’s “The Man Who Could Be King,” based on the Rudyard Kipling short story, in which he plays a military officer who is accepted as a god in Kafiristan, a fighting print. to keep. It’s a perfect role and performance for Connery, whose best work came when he, this former bodybuilder of impeccable strength and magnetism, was honored.

Connery’s confidence manifested itself most dramatically when she was challenged by foes more formidable than a Bond villain. In his Oscar-winning performance in Brian De Palma’s ban-era crime thriller, “The Untouchables,” he is aware of the threat from Al Capone and tells Treasury agent Kevin Costner: “What I’m saying is, what are you prepared for? do? “

Upon accepting the Academy Award, Connery turned to his wife since 1975, Micheline Roquebrune. “By winning this award, it creates a certain dilemma because I had decided that if I was lucky enough to win it, I would give it to my wife, who deserves it,” he said. “But, tonight, I found out behind the scenes they are worth $ 15,000, now I’m not so sure. Micheline, I’m just kidding. It’s yours.”

Connery aged well as an actor, creating more diverse and inquisitive portraits of masculinity. He played an old Robin Hood, with Audrey Hepburn, in “Robin and Marian” (1976), a fuel submarine captain in John McTiernan’s “The Hunt for Red October” and a playful and adorable father to Harrison Ford in “Indiana Jones “by Steven Spielberg. and the last crusade ”(1989).

Another “Indiana Jones,” Connery said, had been the only thing that really tempted him out of retirement. That could be because the flash of mischief that accompanied almost all of Connery’s performances was very much present on “The Last Crusade.” Connery always left you feeling, if not shocked, very blissfully agitated.