[ad_1]

The Milwaukee Bucks’ surprising refusal to go to the court for their NBA playoff game on Aug. 26 was the most important political development in sports in the past 50 years.

In recent years, the prevailing media narrative is that athletes have routinely used their platforms to “raise awareness” or “draw attention” to a social issue.

However, consciousness has its limits. It rarely leads to the kind of structural changes that the Jacob Blake police shooting in Kenosha, Wisconsin seems to require.

In this case, the players faced the moment, marking a fundamental shift in the direction of activism generated by black athletes. The massive player strikes that followed the Bucks’ initial protest weren’t an exercise in conscience, although some commentators framed it that way.

Instead, these athletes were, in effect, going on strike and showing the world how much economic influence they could wield.

Pressure builds

When I began studying black protest speech in sports about 10 years ago, athlete activism seemed to be on the decline.

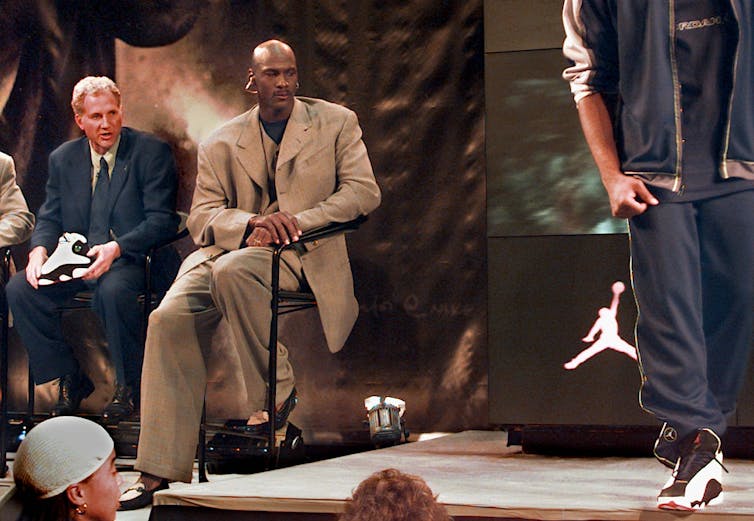

Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods had become marketing demigods, ushering the sport into the rarefied circuits of global capitalism. By signing increasingly lucrative endorsement deals with risk-averse corporate partners, black athletes, critics argued, were trading their conscience for the promise of wealth.

However, the narrative began to change around 2012, when the Miami Heat posed in hooded sweatshirts for a high-circulation photograph intended to protest the murder of Trayvon Martin in Florida.

Two years later, athlete activism accelerated when the Los Angeles Clippers rallied against their team owner, Donald Sterling, for making racist comments. NBA stars wore jerseys that read “I can’t breathe” to protest the murder of Eric Garner by police in New York. And five St. Louis Rams players raised their hands in “no shooting” poses to call attention to the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Vice Sports declared 2014 “the year of the activist athlete.”

Then in 2016, Colin Kaepernick knelt during the anthem to protest police brutality, eventually becoming the avatar of the activist athlete. When the NFL’s biggest stars filmed a #BlackLivesMatter video in the summer of 2020 to protest the murder of George Floyd, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell admitted that “we should have heard sooner,” despite having overseen the Kaepernick’s actual banishment three years earlier.

However, the confidence of professional athletes on Twitter, Instagram and T-shirts often falls short. Yes, they have a huge platform for political discourse and can often use social media to avoid traditional media. But thanks to their relationships with sponsors, advertisers, and television networks, professional sports leagues have an even bigger one.

This gives sports executives like Goodell the power to lead from behind, making the message of the athletes their own.

Perhaps the most cynical use of this technique came in 2017, after Donald Trump said that NFL players who kneel during the national anthem should be fired. When the Dallas Cowboys expressed their desire to kneel in solidarity, they joined arm in arm with team owner Jerry Jones, a vocal Trump supporter, who agreed to participate, as long as it didn’t happen during the anthem.

The corporate dance

Of course, it is possible for activist athletes to compete with leagues for attention and influence. But this often requires a dangerous relationship with corporate power, as when Nike announced its brand partnership with Kaepernick.

“Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything,” said Kaepernick’s Nike ad. This catchphrase, which could easily have been a slogan for the military or the police, reveals the anesthetizing effects that corporate messages can have on politics. Sure, athletes can appear in ads that mention social justice. But ultimately, they are there to sell products and often provide more value to the corporation than they get in return.

AP Photo / Kathy Willens

Furthermore, corporate messages do not depend on moral imperatives, but on prevailing public sentiment and the interest of shareholders. The market offers no guarantee that a company that changes its Twitter avatar to say “Black Lives Matter” will always be more profitable than staying silent or doing the opposite.

Furthermore, it is impossible, by definition, for corporations to send anti-corporate messages. For these reasons, the relationship of athlete activism to corporate power is inherently fragile.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]From talking to acting

This week’s work stoppage in professional sports is the most significant moment in athletes’ activism in half a century, not because it “raised awareness” or “started a conversation,” but because it exercised the most elementary form of political power in the workplace: the strike.

In retiring, professional athletes harnessed their power to exploit, as sociologist Harry Edwards wrote in 1969, “the white man’s economic and quasi-religious involvement in athletics.”

After a summer of racist police violence and protests across the country, the Jacob Blake shooting in Kenosha, Wisconsin forced athletes to confront the futility of persuasion and embrace their ability to influence. T-shirts and TV commercials do not generate phone calls with attorneys general and lieutenant governors, but strikes do.

The same point was made more strongly in 2015, when soccer players at the University of Missouri had their university president fired within 36 hours of announcing a strike for racial justice.

As major media organizations framed the departure as a “boycott” and leagues announced that the games had been “postponed,” these descriptors concealed the threat that striking athletes pose to the economic health of the sport and racial order. In a vivid display of workers’ agency, the black athletes refused to entertain the public and earn money for the wealthy owners of their teams.

This, they said, was not a conflict to be resolved by “listening.” It would require direct financial pressure.

It is tempting to view the spread of the strike through baseball, soccer, football, and even tennis as an expansion of the activist athlete’s platform. But perhaps we should see it as the emergence of interdependent worker collectives. After suspending the season in March, the NBA decided in July to resume play in Orlando at a Disney complex where all participants would undergo regular virus tests and live together in quarantine.

The “bubble” in Orlando was designed to protect the league’s assets from COVID-19. But what if, instead, the players’ forced proximity to each other ended up cultivating a radical consciousness and facilitating a spirit of worker resistance?

It is not entirely clear where the athlete’s blow is headed. The NBA has announced that games will resume, and the NFL and the NFL Players Association issued a joint statement indicating their intention to “use our collective platform to speak out against racism and injustice whenever and wherever they occur.”

The statement is a reminder that when corporate power seeks common cause with workers, the result is almost always “difficult conversations on these issues.” Corporations love conversations. They reduce politics to discourse and anticipate the pace of significant social change.

However, sports organizations tend to move more quickly when their workers refuse to play.

In a polarized political environment under a president willing to stoke racial divide, I see attempts at moral suasion as tears in a poisoned well. What started with the Milwaukee Bucks in Orlando indicates a new form of athlete activism, not because the platform is growing or the storylines become more compelling, but because it avoids the pitfalls of the token show.

Players are leveraging the workforce to do real political work.

[ad_2]