[ad_1]

A comet recently discovered in December last year has already disappeared. It did not reach perihelion, or its closest approach to the Sun. It did not even pass within Earth orbit. However, Comet C / 2019 Y4 (ATLAS) has now been completely shattered.

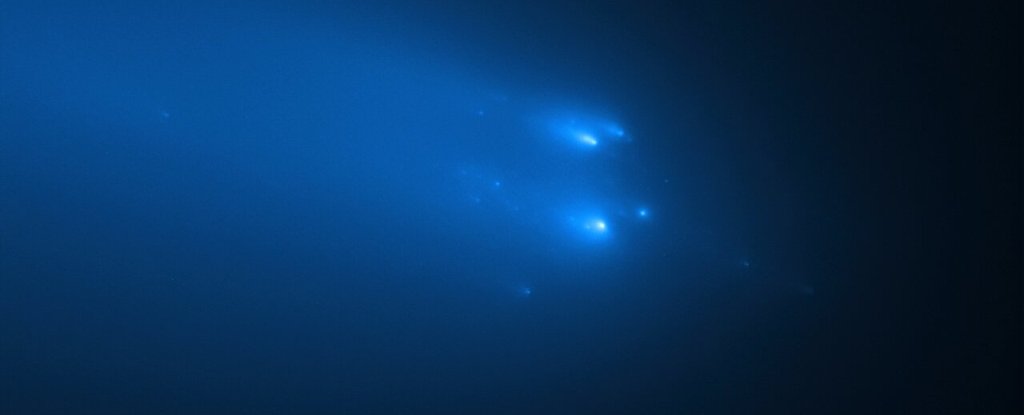

In images taken on April 20 and 23, the Hubble Space Telescope has captured at least 30 and 25 fragments of the comet respectively, traveling together in a group as they continue toward the inner Solar System.

“Their appearance changes substantially between the two days, so much so that it is quite difficult to connect the dots,” said astronomer David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“I don’t know if this is because the individual pieces turn on and off when they reflect sunlight, act like flickering lights on a Christmas tree, or because different shards appear on different days.”

The fragmentation of C / 2019 Y4 (ATLAS) has dashed hopes that the comet is visible to the naked eye from Earth, even in daylight. But while it’s not uncommon for comets to break when they get close to the Sun, it’s rare to catch one on the spot in such spectacular detail.

“This is really exciting, both because such events are super cool to watch and because they don’t happen very often. Most comets that have fragments are too dark to see,” said astronomer Quanzhi Ye of the University of Maryland.

“Events on such a scale only occur once or twice per decade.”

Hubble has managed to solve individual pieces of the comet, originally believed to be up to 200 meters (650 feet) wide, as small as the size of a house, from a distance of 145 million kilometers (90 million miles).

And those chunks could provide clues to the mechanism behind the fragmentation of these peripatetic chunks of ice and rock, a process we still don’t fully understand.

We believe it has to do with the sublimation of cometary ices, as the comet approaches and is heated by the Sun. This degassing produces the classic halo and tail of the comet. But, as those gases leave the comet, they can act as a kind of jet, propelling the comet to spin.

If this spin becomes fast enough, the centripetal forces could exceed the material resistance of the nucleus as the comet divides and fragments under stress.

(NASA, ESA, D. Jewitt / UCLA, Q. Ye / University of Maryland)

(NASA, ESA, D. Jewitt / UCLA, Q. Ye / University of Maryland)

“A more detailed analysis of the Hubble data could show whether this mechanism is responsible or not,” Jewitt said.

We will also have more opportunities to study the shattered comet, which is still on an entry path. Currently, it is within the orbit of Mars, and has not yet passed Earth’s orbit; At its current speed, the comet will do so at a distance of 115 million kilometers (71 million miles) from Earth on May 23.

From there, it will continue toward the Sun, approaching 37 million km (23 million mi) on May 31, within Mercury’s average orbit of 57.9 million km (36 million mi).

And from there, the pieces will disappear again into the far reaches of the Solar System in its 6,000-year loop orbit around the Sun, and we’ll never see them again in our lives.

Astronomers, of course, will take the opportunity to continue monitoring the cloud with any available telescope to observe how it changes and try to find more clues about how comets break.

“Regardless,” Jewitt said, “it’s pretty special to look at this dying comet with Hubble.”