[ad_1]

Urgent genome sequencing in the case of an Air New Zealand crew member with Covid-19 could provide further clues as to where they became infected.

The person tested positive during the routine test in China and was flown back to New Zealand on a cargo flight yesterday to avoid contact with other passengers.

The crew member and seven of his close contacts are now in quarantine at the Auckland Jet Park Hotel.

Health officials have been investigating and tracking the case as if it were a confirmed community case in New Zealand.

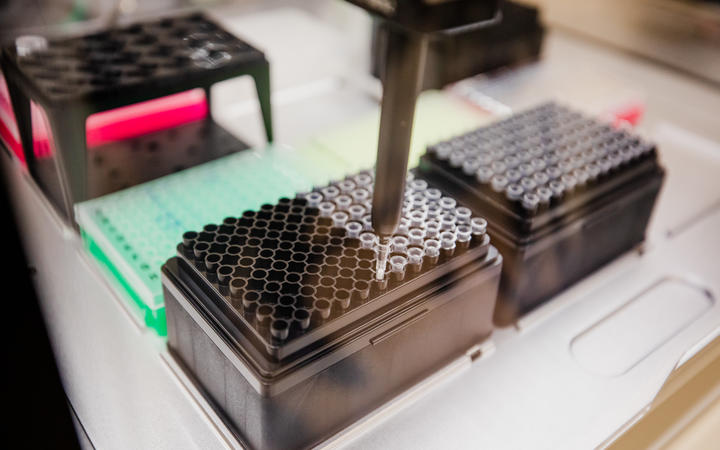

ESR is racing to complete the genome sequence for this case and will compare it to others in a database.

“We have an almost complete picture of everything in the country. But there is still a small chance that it is something that we have not yet detected in the community,” said ESR scientist Dr. Joep de Ligt. Control.

“As I say, it is a small possibility, because there is good evidence in New Zealand and we have an almost complete picture, but it is something that we cannot exclude as a possibility.”

“From the complete description of the cases, there would be a coverage of about 80 percent. And in terms of the last months, 90 percent is complete.

“There are a couple of cases where sometimes we don’t have enough RNA to get a complete genome, but it is about as complete as we can get.

“That could be because the person was historically infected and they don’t have a lot of virus in their body anymore. That’s what happens more typically, or for some reason there just isn’t a lot of RNA in the sample.”

Dr de Ligt said that ESR scientists were trying to keep coverage above 90 percent.

“We will try to sequence any sample just to make sure we can get as close to that mark as possible. But if you have that kind of level of coverage, then you can start to draw some conclusions about the missing data.

“What is promising is that if it is these historical cases, they are also less likely to lead to a spread in the future, so it is not that serious a problem if they are ignored.”

There is a global database of genome sequences for Covid-19 chains, where scientists can upload their information and download other sequences from other countries.

“So there is a pretty good international effort where the exchange helps us with this kind of research,” said Dr. de Ligt.

“In this case, if we found a link to one of our New Zealand genomes … that tells us with pretty certainty that they are part of the same chain of transmission as we call it.

“That means that in terms of investigations, we can start to see how those two people might have interacted, and that’s probably through an additional person, but we can start looking for the missing links.

“If we don’t find a link to a New Zealand genome, then we can look at those international genomes. If it’s very close to one of those international genomes, it’s more likely what we call a travel-related genome.” infection, where we could start to look in more detail at the airports, or the airlines involved in the movements of a certain person.

“Some genomes are quite unique. Some of the ones we have in New Zealand, because we have a quarantine system, have not spread to any other part of the world.

“So if we find a mutation that is like this, that hasn’t been seen anywhere else, that’s pretty sure. But if it’s a sequence that’s widespread around the world, then it becomes less secure. So it really depends. of the individual genome we find, how safe or uncertain we can be. “

A genome sequence is 30,000 As, Ts, Cs and Gs in a row, Dr. de Ligt said. “This is what the genome sequence looks like.

“If we want to abstract it even further, it’s a bit like all viruses carry an instruction book. And those instructions, when they enter human cells, are used to make more copies of the virus.

“And that instruction book, that’s the genome.

“It’s almost a recipe that defines how the virus is produced. Sometimes changes occur in that recipe, like if you get a recipe from the Internet and read that there is only one clove of garlic and you really love garlic, you could make two or three cloves of garlic.

“That’s your version of that recipe, and if you later give that recipe to someone else, they will have that initial version with more garlic.”

Dr. de Ligt said that in the cluster of Covid-19 cases involving a member of the Defense Forces, all but one of the genomes were identical.

“So they are exactly the same recipe, so no changes are made. And that increases the confidence that they recently related to each other.”

However, genome sequencing did not explain how the virus is transmitted from one person to another.

“That is where the epidemiological research that the public health units and our epidemiologists come into play,” he said.

“It’s about when a person starts showing symptoms, what was their movement, what were their contacts, that will dictate the direction of that transmission chain.

“Every time the virus passes to a new person, there is a chance that a difference will occur. So the more people it goes through, the more likely that will happen.

“What, for example, we saw in August in Auckland was that at some point we had cases that were four mutations or four changes from the original outbreak.

“So as time goes by, you expect those mutations to happen. If you suddenly find someone who has two or three mutations than you previously knew about, that’s when you really start scratching your head about missing links and that guy. of things, because that must have gone through several people to accumulate that amount of mutations “.