[ad_1]

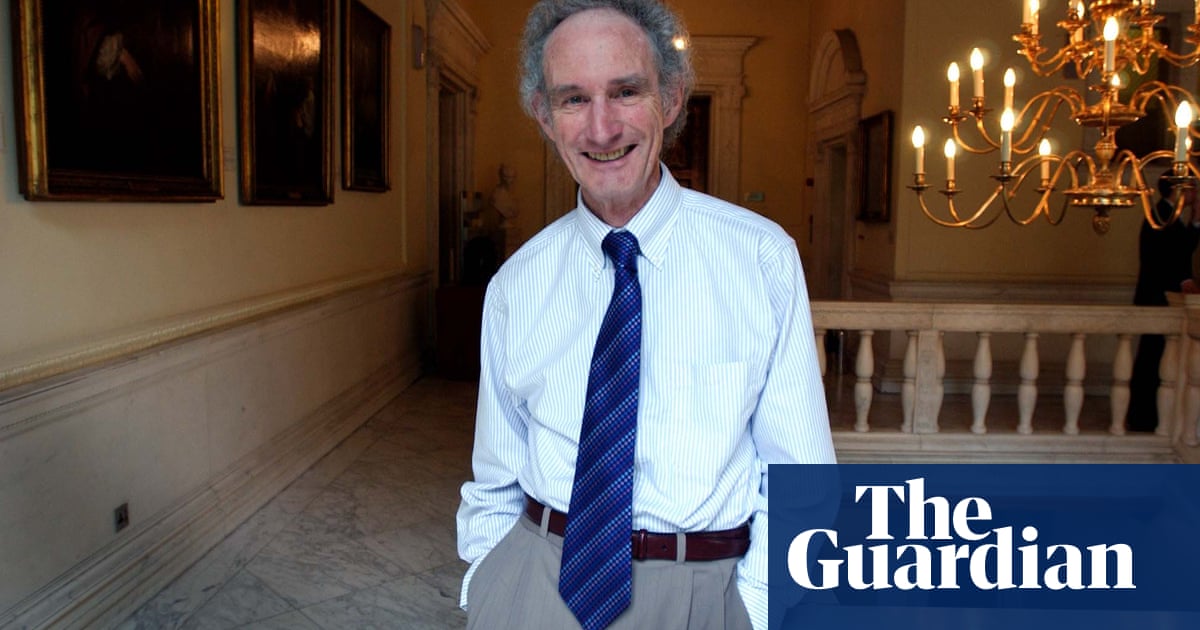

Australian pioneering scientist Robert May, whose work in biology led to the development of chaos theory, died at the age of 84.

Known as one of Australia’s most accomplished scientists, he served as the UK’s top scientific adviser, was chairman of the Royal Society, and was appointed lord in 2001.

Born in Sydney on January 8, 1938, May’s work was influential in biology, zoology, epidemiology, physics, and public policy. More recently, he applied scientific principles to the economy and modeled the cause of the 2008 global financial crisis.

On Wednesday, her friends and colleagues paid tribute to a man who they said was a gifted polymic and a “True giant” among scientists.

Professor Ben Sheldon, head of the Oxford zoology department, said May’s work had “changed entire fields” of science.

The current president of the Royal Society, Venki Ramakrishnan, said May was “an extraordinary man” who “drove a great change in all areas in which he committed his talents.”

“Bob was a natural communicator and used all available avenues to share his message that science and reason should be at the heart of society, and he did so with a fervent pursuit that resonates with those of the founding members of society “

Professor Joss Bland-Hawthorn, director of the Sydney Institute of Astronomy, said May’s death was “a great loss to Australian research.”

Bland-Hawthorn first met in May at the University of Sydney in the early 2000s and the two dined together as companions at Merton College, Oxford.

“His career, in layman’s terms, was getting to the bottom of what complicates matters,” he told Guardian Australia.

“He didn’t look much for titles. It was Lord May, Baron of Oxford, but he had no pretense. In fact, many of my stories about him are quite rude. He used to swear a lot.

“One night at dinner, he told me that he was the first person in the history of the Royal Society to speak ill within minutes. He said that not even Isaac Newton accomplished that. “

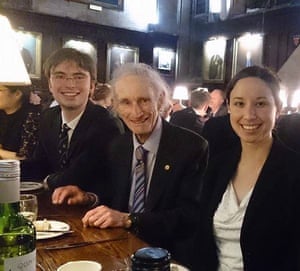

Dr. Benjamin Pope, an Australian astrophysicist and student at Oxford from 2013 to 2017, said May was a role model, and meeting him was the highlight of her university career.

“I realized his accomplishments almost as soon as I learned something about physics in college,” Pope told Guardian Australia. “My first contact with computer programming was at the University of Sydney, in first-year physics, where the example is to recreate Robert May’s experiment with the branch diagram and the logistics map.

“Your bifurcation diagram is one of the iconic diagrams in physics,” he said. “[And] He made what was between three or four independent discoveries that led to chaos theory. You may have heard of the butterfly effect … May’s is probably the other model of fundamental, computational chaos. “

May attended Sydney Boys High School and the University of Sydney, where she completed a PhD in superconductivity.

Between 1995 and 2000 he was the Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Government, was knighted in 1996 and was Chairman of the Royal Society between 2000 and 2005.

In 2007, he won the Copley Medal, the Royal Society’s most prestigious award, previously won by Stephen Hawking, Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, and Dorothy Hodgkin, among others.

Pope said he had always admired May for her interest in political and environmental issues.

“He contributed not only to theoretical physics, but also to highly applied knowledge, advising governments on serious public policy problems,” he said. “Robert May is a great example of how a scientist can contribute to all those different spheres in that way.”

Pope said he met May in 2015 at a student dinner he helped organize, where May was a keynote speaker.

“He knew everything about economics, politics, philosophy, and mathematics. He was arrogant, he had this deep voice, with an Australian accent, which was rare enough for a baron.

“It really showed that he cared about people, he had a social conscience,” Pope said. “It was really a highlight of my entire degree in physics in England to meet my role model and have dinner with him.”

May was first elected to membership in the Royal Society in 1971, and her other awards include the Craaford Prize, the Blue Planet Prize, and the Balzan Prize.

[ad_2]