[ad_1]

The loss of ice in Antarctica and Greenland represents about a half inch of sea level rise between 2003 and 2019.

Using the most advanced Earth observation laser instrument POT If you’ve ever flown in space, scientists have made precise and detailed measurements of how the elevation of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets has changed for 16 years.

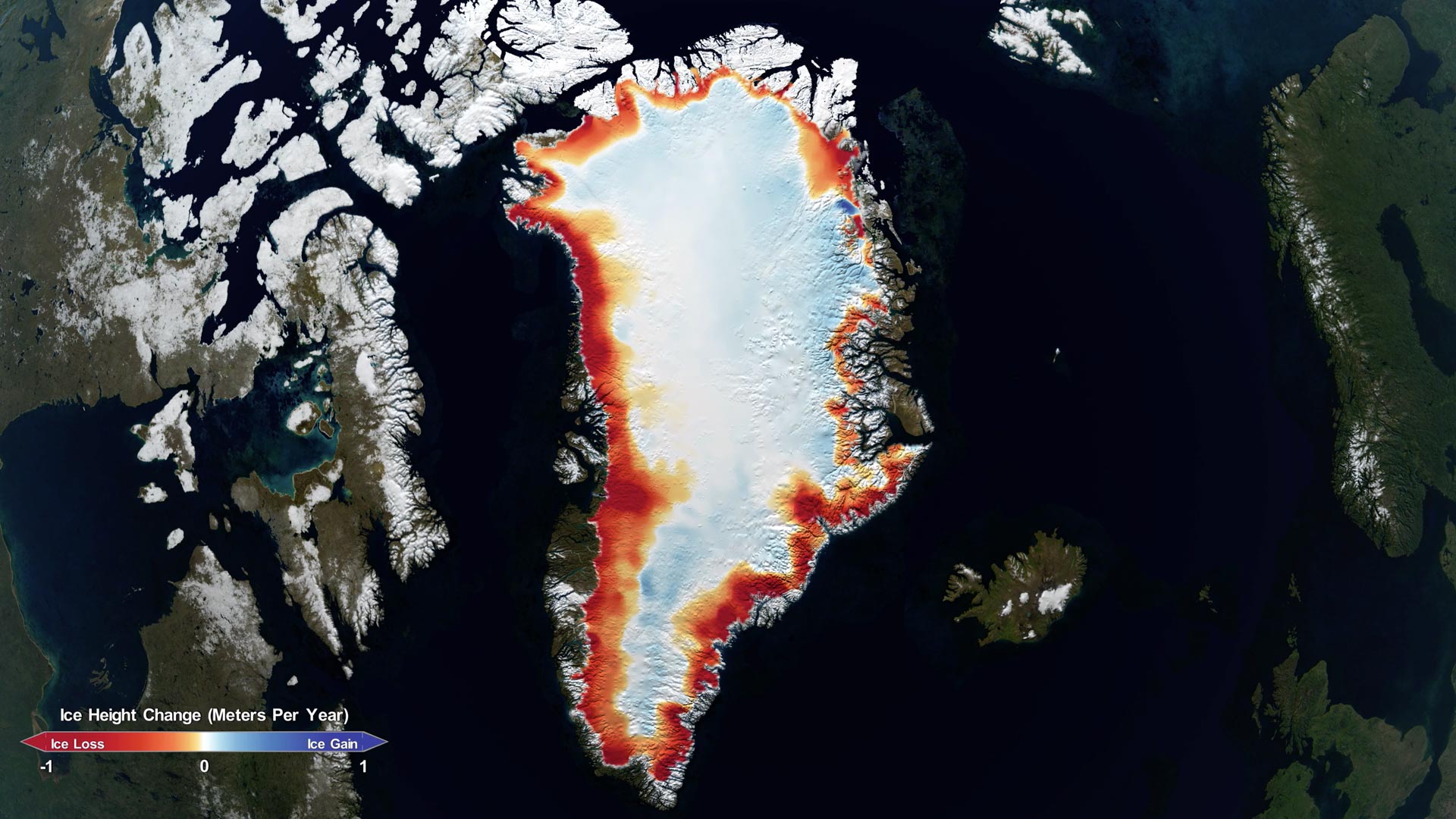

The results provide insight into how the polar ice sheets are changing, which definitely shows that small ice gains in East Antarctica are overshadowed by massive losses in West Antarctica. Scientists discovered that Antarctica’s net loss of ice, coupled with declining Greenland ice sheets, has been responsible for 0.55 inches (14 millimeters) of sea level rise between 2003 and 2019, slightly less than one third of the total amount of sea level rise. observed in the world’s oceans.

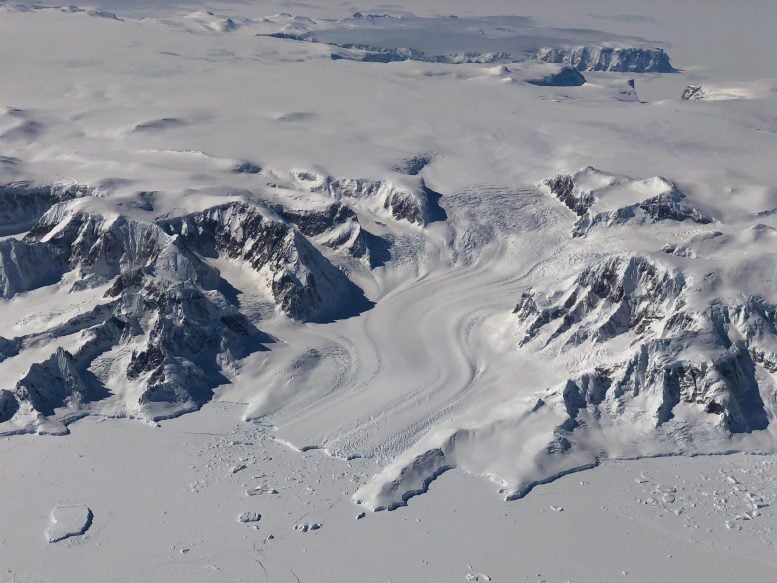

The Kangerdlugssup (pictured) and Jakobshavn glaciers in Greenland have lost approximately 14 to 20 feet (4 to 6 meters) of elevation per year in the past 16 years. Image credit: NASA / Jim Yungel

The findings come from NASA’s Ice, Cloud, and Ground Elevation Satellite 2 (ICESat-2), which was launched in 2018 to make detailed measurements of global elevation, even over Earth’s frozen regions. By comparing recent data with measurements taken by the original ICESat from 2003 to 2009, the researchers have produced a comprehensive portrait of the complexities of ice sheet change and ideas about the future of Greenland and Antarctica.

The study found that the Greenland Ice Sheet lost an average of 200 gigatons of ice per year, and the Antarctic Ice Sheet lost an average of 118 gigatons of ice per year.

One gigaton of ice is enough to fill 400,000 Olympic pools or cover New York’s Central Park with ice over 1,000 feet (300 meters) thick, reaching higher than the Chrysler Building.

Climate change is reshaping the ice sheets in the Arctic and Antarctic, and NASA’s ICESat and ICESat-2 satellites help researchers determine what those disturbances are like.

“If you look at a glacier or ice sheet for a month or a year, you’re not going to learn much about the weather,” said Ben Smith, a glaciologist at the University of Washington and lead author of the new article, published online in Science on April 30. “We now have a 16-year gap between ICESat and ICESat-2 and we can be much more confident that the changes we are seeing on the ice have to do with long-term changes in the climate.”

The ICESat-2 instrument is a laser altimeter, which sends 10,000 pulses of light per second to the Earth’s surface and measures the time it takes to return to the satellite, within a billionth of a second. The pulse rate of the instrument allows a dense measurement map on the ice sheet; Its high precision allows scientists to determine how much an ice cap changes over a year to an inch.

Using data from the ICESat and ICESat-2 laser altimeters, the scientists accurately measured the amount of ice lost from the ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland between 2003 and 2019. The Antarctic Peninsula, seen here, was one of the fastest changing regions of the continent. . Credit: NASA / K. Ramsayer

The researchers tracked previous ICESat measurements and overlayed the tracks from the 2019 ICESat-2 measurements, and took data from the tens of millions of sites where the two data sets intersected. That gave them the elevation change, but to find out how much ice was lost, the researchers developed a new model to convert the change in volume to change in mass. The model calculated the densities across the ice sheets to allow calculation of the total mass loss.

“These early results analyzing land ice confirm the consensus of other research groups, but also allow us to see the details of the change in individual glaciers and ice shelves at the same time,” said Tom Neumann, ICESat-2 project scientist at The NASA. Goddard

In Antarctica, for example, detailed measurements showed that the ice sheet is thickening in parts of the interior of the continent as a result of increased snowfall, according to the study. But the loss of ice from the continent’s margins, especially in West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula, far outweighs any gains inland. In those places, the loss is due to ocean warming.

In Greenland, there was a significant amount of thinning of the coastal glaciers, Smith said. The Kangerdulgssuaq and Jakobshavn glaciers, for example, have lost 14 to 20 feet (4 to 6 meters) of elevation per year; glacial basins have lost 16 gigatons per year and 22 gigatons per year, respectively. The warmer summer temperatures have melted ice from the surface of glaciers and ice sheets, and in some basins the warmer ocean water erodes the ice on their fronts.

“The new analysis reveals the response of ice sheets to climate change in unprecedented detail, revealing clues as to why and how ice sheets are reacting the way they are,” said Alex Gardner, a glaciologist at the Laboratory for NASA Jet Propulsion in Southern California. and co-author of the Science article.

The study also examined ice shelves, the floating ice masses at the downstream end of glaciers. These ice shelves, which rise and fall with the tides, can be difficult to measure, said Helen Amanda Fricker, a glaciologist at the Scripps Institute for Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, and co-author of the Science article. Some of them have rough surfaces, with cracks and ridges, but the precision and high resolution of ICESat-2 allows researchers to measure overall changes.

This is one of the first times that researchers have used laser altimetry to measure the loss of floating ice shelves around Antarctica simultaneously with the loss of the continent’s ice sheet.

The researchers found that ice shelves are losing mass in West Antarctica, where many of the continent’s fastest-moving glaciers are also found. Thinning patterns on ice shelves in West Antarctica show that the Thwaites and Crosson ice shelves have thinned the most, averaging about 16 feet (5 meters) and 10 feet (3 meters) of ice per year, respectively.

Melting ice from ice shelves does not raise sea level as it is already floating, just like an ice cube in a cup filled with water does not overflow the glass when it melts. But the ice shelves provide stability for the glaciers and the ice sheets behind them.

“It is like an architectural buttress that supports a cathedral,” Fricker said. “Ice shelves support the ice sheet. If you remove the ice packs, or even thin them, you’re reducing that reinforcing force, so grounded ice can flow faster. “

[ad_2]