Nasal delivery produces more widespread immune response than intramuscular injection

Hassan et al.

Hassan et al.

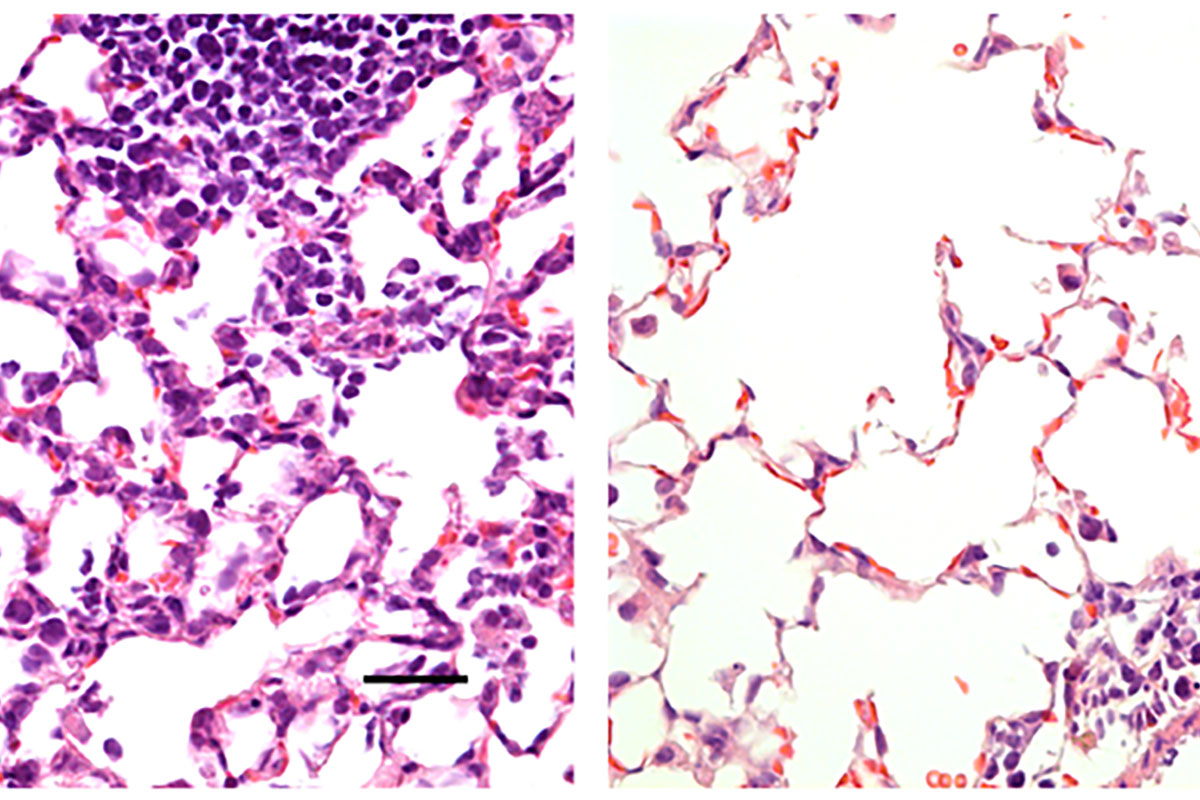

Researchers from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Louis have developed a COVID-19 vaccine delivered through the nose that protects mice from the virus. Tone is mucosal lung tissue infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. On the left is lung tissue from a mouse that received a control vaccine that did not produce protective effects. It shows a large number of inflammatory cells. To the right is lung tissue from a mouse given a nasal vaccine encoding the virus’ spike protein. The vaccine protects against infection, and large numbers of inflammatory cells are absent.

Scientists at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Louis have developed a vaccine that targets the SARS-CoV-2 virus, can be given in a single dose through the nose and is effective in preventing infection in mice that are susceptible to the new coronavirus. The researchers next plan to test the vaccine in nonhuman primates and humans to see if it is safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 infection.

The study is available online in the journal Cell.

Unlike other COVID-19 vaccines in development, this one is delivered through the nose, often the first side of infection. In the new study, the researchers found that the nasal delivery route produced a strong immune response throughout the body, but it was particularly effective in the nose and airways, preventing the infection from persisting in the body.

“We were pleasantly surprised to see a strong immune response in the cells of the inside of the nose and upper respiratory tract – and a deep protection against infection with this virus,” said senior author Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser professor of medicine and a professor of molecular microbiology, and of pathology and immunology. “These mice were well protected against diseases. And in some of the mice we saw evidence of sterilization of immunity, where there is no sign of infection after the mouse has been challenged with the virus. “

To develop the vaccine, the researchers inserted the virus’ spike protein, which coronavirus uses to invade cells, into another virus – called an adenovirus – that causes the common cold. But the scientists tweaked the adenovirus, making it unable to cause disease. The harmless adenovirus carries the spike protein in the nose, allowing the body to develop an immune defense against the SARS-CoV-2 virus without becoming ill. In another innovation beyond nasal delivery, the new vaccine incorporates two mutations into the spike protein that stabilize it in a specific form that most favors the formation of antibodies against it.

“Adenoviruses are the basis for many research vaccines for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, such as Ebola virus and tuberculosis, and they have good safety and efficacy registers, but not much research has been done with nasal delivery of these vaccines,” said co -enior author David T. Curiel, MD, PhD, the Distinguished Professor of Radiation Oncology. “All other adenovirus vaccines in development for COVID-19 are delivered by injection into the arm and thigh muscles. The nose is a new route, so our results are surprising and promising. It is also important that a single dose produced such a robust immune response. Faxes that require two doses for complete protection are less effective because some people never get the second dose for various reasons. “

Although there is an influenza vaccine called FluMist that is delivered through the nose, it uses an attenuated form of the live influenza virus and can not be controlled to certain groups, including those whose immune system is compromised by diseases such as cancer , HIV and diabetes. In contrast, the new COVID-19 intranasal vaccine in this study does not use a live virus that can replicate, probably making it safer.

The researchers compared this vaccine given to the mice in two ways – in the nose and via intramuscular injection. While the injection elicited an immune response that prevented pneumonia, it did not prevent infection in the nose and lungs. Such a vaccine may reduce the severity of COVID-19, but it would not completely block infection or prevent infected individuals from spreading the virus. In contrast, the nasal delivery route prevented infection in both the upper and lower respiratory tract – the nose and lungs – suggesting that vaccinated individuals would not spread the virus or develop infections elsewhere in the body.

The researchers said the study was promising, but warned that the vaccine has so far only been studied in mice.

“We will soon begin a study to test this intranasal vaccine in nonhuman primates with a plan to enter human clinical trials as soon as possible,” Diamond said. “We are optimistic, but this must continue through the right evaluation discipline. In these mouse models, the vaccine is very protective. We look forward to starting the next round of studies and finally testing it in humans to see if we can induce the kind of protective immunity that we think will not only prevent infection but also limit pandemic transmission of this virus. “