The difficulties of NASA sending humans back to the moon by 2024 are long – not zero but very close.

Probably the biggest closest obstacle to a space agency is funding. Specifically, NASA needs an additional 3. 2.32 billion in fiscal year 2021 to allow contractors to begin building one or more landers to take astronauts down from a lunar orbit. This is a 12 percent increase in NASA’s overall budget.

The 2021 fiscal year begins on October 1, in one week. The U.S. Congress recently passed a “continuous resolution,” which will provide funding to the government by Dec. 11, after the 2020 election, in the hope that the House and Senate can agree on a budget that prioritizes funding for the remainder of the fiscal year. Is.

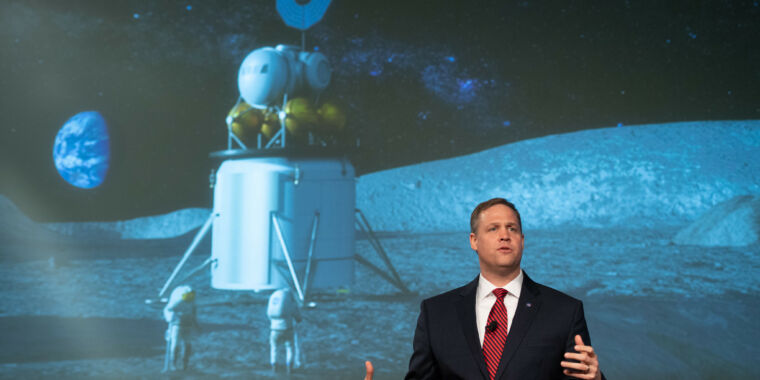

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstein said this week that it would be appropriate to work to fund the Artemis Moon program before the end of this year. “If we can do that before Christmas, we’re still on the verge of a 2024 lunar landing,” he told reporters.

The real question is whether Congress, if it can agree on a budget for FY 2021 in this age of partisanship, is so inclined to support funding for landlords. This is a brand new program that will eventually meet the needs of billions of dollars. In a discussion earlier this year, U.S. The House provides only $ 600 million, or less than one-fifth of NASA’s budget, which outlines its needs for next year.

So says the Senate

Wednesday provided the first opportunity to assess, at least in public, whether the Senate would further support the Artemis program and its aggressive 2024 goal.

In his opening remarks, there were words to say about Artemis, a Kansas Republican who chairs a Senate subcommittee overseeing NASA’s budget, Jerry Moran. But he noted that the request for a larger budget by NASA came amid a backdrop of an epidemic and consequent financial crisis.

“Our world has changed significantly since the initial release of the budget, and I’m looking forward to discussing how NASA is adapting to our new and unprecedented environment as we move forward with Artemis,” Moore said.

The committee’s ranking Democratic member also appeared less supportive. Ginny Shahi of New Hampshire noted that NASA’s proposed budget again reduced funding for STEM education and did not support the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. “We know NASA needs to have more than just one moonshot,” he told Bridenstein. Shaheen called the 12 per cent budget increase “liberal”.

Later during a question-and-answer period, Moore asked Brydenstein if it would be more practical for NASA to select a single contractor to make a quick lander so that the agency could concentrate its resources.

Bridenstein pushed this back, citing the value of competition. Earlier this year, the space agency selected three teams led by Blue Origin, Dynamics and SpaceX to roll out lender proposals and tell NASA how much government funding they would need to complete the project by 2024. With this information, NASA plans to “down-select” from this initial group of three landing teams in February.

One, two, or three?

In recent months, there has been a flurry in the aerospace community, with one or more lender teams pushing for all funding this February that other teams may not be able to meet the technical challenge by reporting.

But Bridenstein seems committed to moving forward with two or more teams. “I’m worried about going down one,” he said. “When you eliminate competition, you end up with programs that inevitably pull out and outperform.” With at least two providers competing, Brydenstein said, NASA will end up in a “virtue cycle” where teams are investing their money and pushing as hard as possible.

For the latest model of success, he cited the commercial crew program, in which SpaceX and Boeing participated to fly astronauts to the International Space Station. SpaceX won the competition and was returned by NASA in 2014 under a “fixed price” agreement. Having two competitors allowed the companies to continue to move forward despite technical challenges, Brydenstan said.

Whether they fund Artemis or not, legislators will have some tough numbers to consider for the program. In the “Artemis Plan” document released on Monday, NASA for the first time put the exact dollar figure of the estimated cost of landing on the moon by 2024: 27.9 billion. Of which .1 16.1 billion will go towards the cost of developing the “early” human landing system. These are the funding requirements by FY2025.