It was 1952, and Alan Turing was to reshape the understanding of the human biology.

In the landmark paper, the English mathematician introduced what became known as the Turing pattern – the assumption that the dynamics of certain uniform systems can give rise to static patterns when disturbed.

Such ‘disruption order’ has become the theoretical basis of all sorts of bizarre, repetitive motives found in the natural world.

That was a good theory. So good, in fact, that even decades later, scientists are still looking for stunning examples of it in unusual and exotic locations: real-world Turing patterns, places came to life that Turing never got a chance to see for himself.

The latest incarnation of this theoretical phenomenon has turned out to be fairy circles – a mysterious formation of desert grass growing around circular patches of dry clay, first documented in the Namib Desert of South Africa.

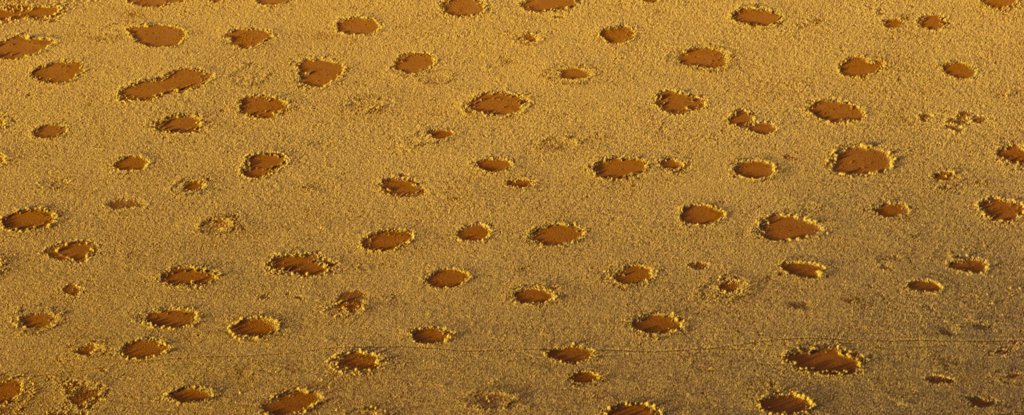

Drone image of Australian Australian fairy circles. (Stephen Gatzin / University of Göttingen)

Drone image of Australian Australian fairy circles. (Stephen Gatzin / University of Göttingen)

Descriptions for their existence range from mythology to the physical, and a few years ago, their origins are still in debate. Initially, one view was that strange circles were due to permanent activity under African soil – but then the discovery of fairy circles in the Australian outback further complicated the story, with fairy circles found without any link to the composite.

Alternatively, scientists have proposed that fairy circles are the result of the arrangement of plants to create limited water resources in harsh, arid environments.

That sounds plausible, and if true, it would be another naturally occurring example of a Turing pattern. While there isn’t really much empirical evidence to support this hypothesis, the researchers say, physicists who model such theories on Turing dynamics rarely even do field work in the desert in support of their ideas.

“There is a strong imbalance between theoretical botanical models dello, their A priority The lack of assumptions and empirical evidence that modeling processes are ecologically sound is appropriate, “a team led by ecologist Stephen Gatzin of the University of Göttingen in Germany has revealed in a new paper.

To bridge this gap, Gatzin and fellow researchers used drones equipped with multispectral cameras to survey fairy circles near Newman’s mining town in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

According to one of the team’s hypotheses, the arrangement of the touring pattern of fairy circles between grasses with greater dependence on moisture will be stronger.

By analyzing the spatial isolation of both high and low life grasses, and using humidity sensors to check the readings on the ground, the team found that healthy, high-living grasses are more systematically involved in fairy circles than low-life grasses.

In other words, for the first time, we have laboratory data that fairy circles are a match for the decades-old theory of Turing.

“The interesting thing is that grasses are actively engineering their own environment by creating patterns of parallel distances,” says Gatzin.

“Vegetation benefits from the extra water supplied by large fairy circles, and therefore keeps the arid ecosystem functioning even in very harsh, arid conditions. Without self-organization of grasses, the area will probably become a desert desert.

According to the researchers, the grass that forms the fairy circles grows simultaneously in a cooperative fashion by modifying their environment to better cope between near-permanent aridity of a fairly dry ecosystem.

The team says more fieldwork will still be needed to validate the mathematical models, but so far, it seems we are closer than ever before closing the book on this mysterious phenomenon.

The authors explain that “by creating periodic gap patterns, plants benefit from the additional water resources provided by fairy circle barriers,” and similarly keep the ecosystem operating at lower rainfall values than plants. “

These findings are reported Journal of Ecology.

.