Researchers have detected artificial mercury contamination at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest ocean trench on the planet.

A team of scientists identified methylmercury, a toxic form of mercury that easily accumulates in some animals, in fish and crustaceans that live in the ditch, which reaches depths of around 36,000 feet.

Mercury can be released into the environment from natural sources, such as volcanic eruptions. However, much of the mercury introduced into the oceans comes from human activities, such as burning coal and oil, or mining and producing metals.

Mercury is a powerful neurotoxin that can accumulate to harmful levels in some marine species. Humans have tripled the amount of the substance that is either introduced into the atmosphere, or deposited on Earth’s surface and Earth’s oceans, every year.

For a study presented at the Goldschmidt Geochemistry conference, a team led by Joel Blum of the University of Michigan wanted to learn more about where human-derived mercury is transported in the oceans, in order to make better predictions of how changes Mercury emissions affect levels of the substance in the marine environment and in fish eaten by humans.

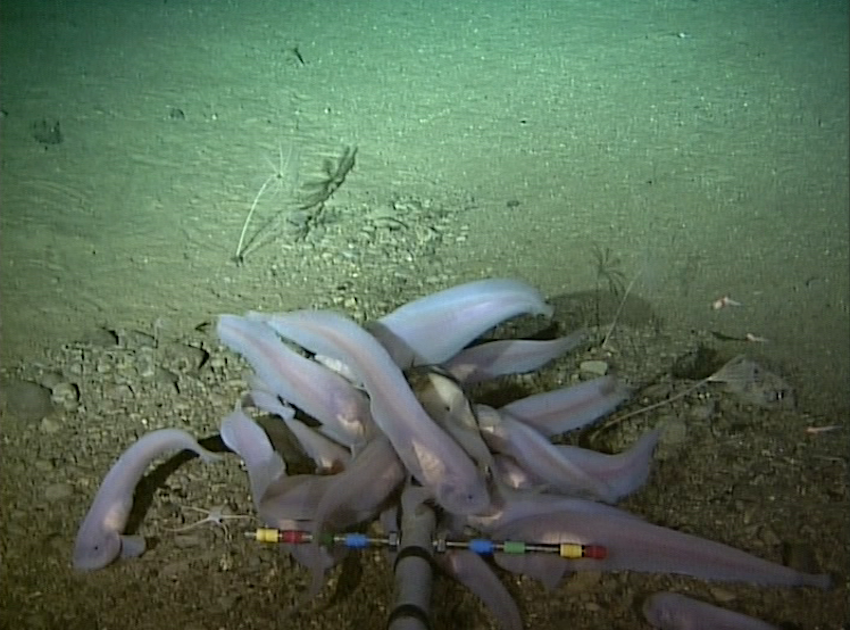

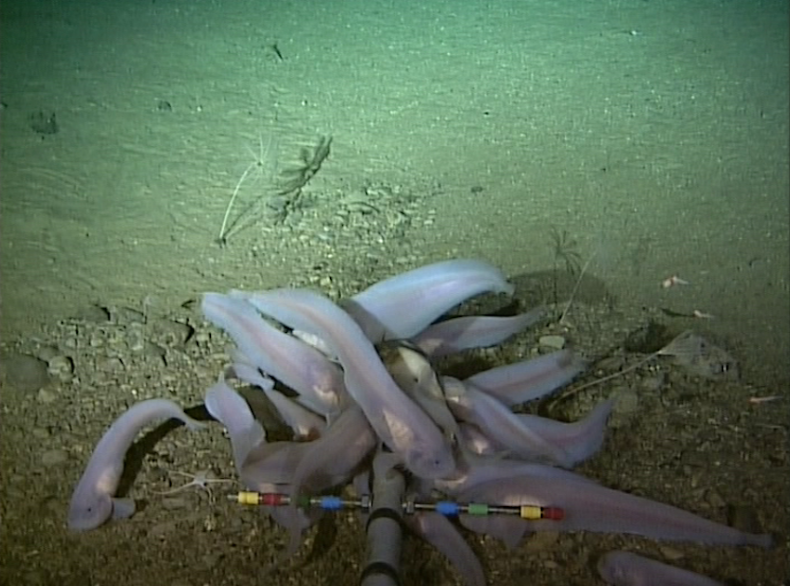

In the investigation, Blum and colleagues collected samples of fish and crustaceans at depths of 7 and 10 kilometers (about 23,000 and 33,000 feet respectively) in the Mariana Trench near the Philippines and the Kermadec Trench off New Zealand, which reaches a depth of about 33,000 feet

Scientists detected mercury in the sampled species, with the substance’s particular chemical signature indicating that it originated largely in the atmosphere and fell into the ocean through rain.

They were able to conclude this, because mercury’s chemical signature, or “isotopic composition,” of the ocean floor coincided with the reading of mercury found in animals living at depths of around 1,300-2,000 feet in the Central Pacific.

According to Blum, some of the mercury they detected could come from natural sources, but most of it probably originated from human activities. The researcher said that human-derived mercury exceeds natural emission by about three times.

Alan Jamieson

The team’s analysis suggested that after being deposited in the upper parts of the ocean through rain, much of this mercury would have gradually sunk to the bottom of the trenches within the carcasses of dead fish and marine mammals. When the carcasses reach the ocean floor, they provide food for scavenging species of fish and crustaceans.

“The key finding is that mercury released by humans and deposited from the atmosphere to the surface of the oceans is being transported to the deepest and most remote environments in the ocean,” Blum said. Newsweek.

Scientists previously knew that human-derived mercury could be found in some of Earth’s most remote terrestrial ecosystems, such as the Arctic and Antarctic. But it was unclear if there was mercury near the bottom of the Mariana and Kermadec trenches.

Mercury can move up the food chain after being ingested by smaller species, which in turn are eaten by larger animals. This means that harmful levels can build up in larger animals. In fact, humans who eat large amounts of fish are in danger of mercury poisoning, which can lead to neurological damage, cardiovascular risks and other health effects, and developing fetuses are particularly vulnerable.

Another independent team of scientists, led by Ruoyu Sun of Tianjin University, China, also detected mercury in marine species living in the furthest depths of the Mariana Trench, according to more research presented at the Goldschmidt Geochemistry conference.

“We are now learning from these two studies that the effects of this deposition have spread across the ocean to the depths of the sea and the animals that live there, which is another indicator of the profound impact of modern human activities on the planet.” Ken said. Rubin, from the University of Hawaii’s Department of Earth Sciences, who was not involved in the investigation of either team, said in a statement.