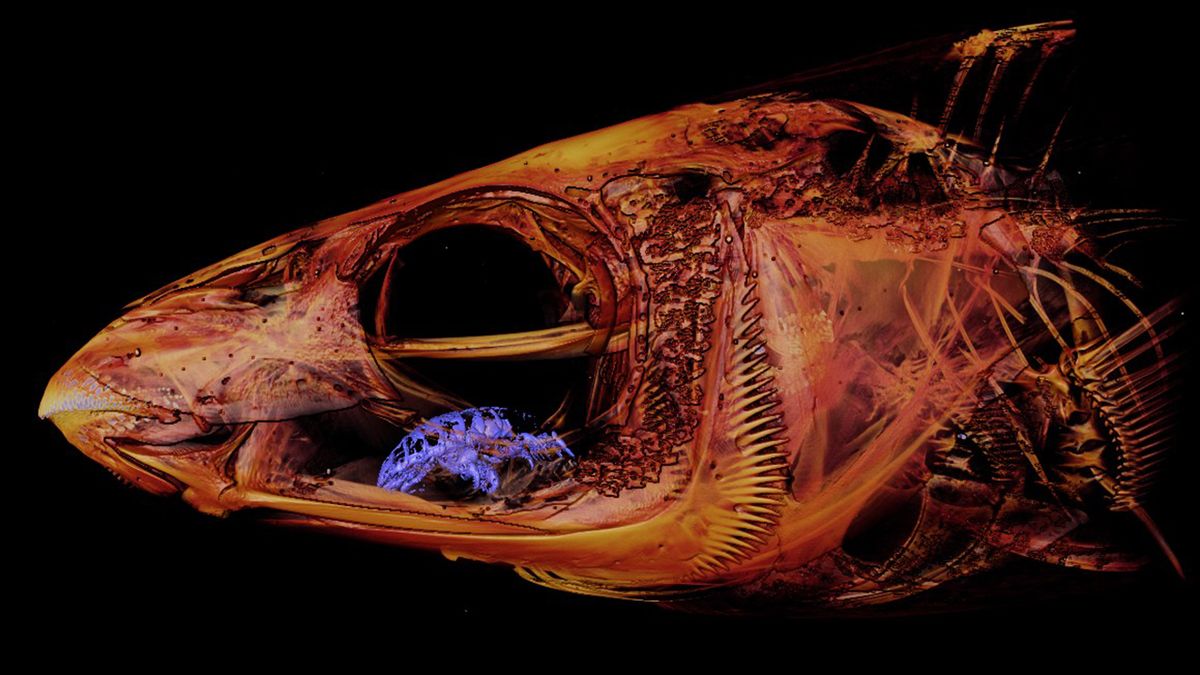

When scientists recently x-rayed a fish’s head, they found a gruesome sidewalk: A “vampire” dish had swallowed its host’s tongue, then replaced it.

The buglike isopod, also called a tongue-biter as a tongue-eating lice, sighs its blood meal from the tongue of a fish until its entire structure disappears. Then the true horror begins, as the parasite takes the place of the organ in the mouth of the still-living fish.

Biologist Kory Evans, an assistant professor in the Department of BioSciences at Rice University in Houston, Texas, discovered the tongue-in-cheek digitization of fish skeletons. He shared images of the surprising and terribly fine on Twitter on August 10: “Mondays are not usually this event,” Evans joked in the tweet.

Related: What the heck?! Images of extreme oddities of evolution

There are about 380 species of tongue-eating isopods, and most focus on a specific fish species as their host, according to the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town, South Africa. This type of isopod enters the body of a fish through the keel, pinches the tongue and begins to feed, releasing an anti-coagulant to keep the blood flowing. The parasite grips the base of the tongue tightly with its seven pairs of legs, which reduces the blood supply, so that the organ eventually atrophies and sinks, according to the Australian Museum.

From that moment on, the body of the isopod serves as a functional tongue for the fish, while the tongue bite continues with the mouse of the fish, according to Rice University’s Coral Reefs Blog. This partnership between a fish and its living tongue can last for years; In many cases, fish are known to survive their tongue replacement parasites, Stefanie Kaiser, a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in Wellington, New Zealand, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Evans opposed the fish and its macabre ‘living tongue’ as part of a scan initiative for a family of coral reef fish called wrasses, he told Live Science. The goal of the project is to generate a 3D X-ray database of skeletal morphology for this fish group, making it available to researchers around the world, Evans said. He often shares examples of the scans on Twitter, under the hashtag #backdatwrasseup.

That morning, “I did something called digitization,” he explained. “I compare skull shapes of all these different fish to each other, which requires placing landmarks – digital markers – on different parts of the body.” In one particular wrasse, a herringbone (Cyaxomelas of Odax) from New Zealand, Evans noticed something strange in his mouth.

“It looked like it had some kind of insect in its mouth,” Evans said. “Then I thought, wait a minute; this fish is a herbivore, it eats seaweed. So I picked up the original scan, and look, look, it was a tongue-eating lice.”

On Mondays, these are usually not events. This morning I found an isopod (pear) with tongue food in one of our wrasse scans while digitizing. These parasites attach themselves to the tongues of fish and effectively become the new tongue … horrifying #backdatwrasseup pic.twitter.com/axlraUrh8WAugust 10, 2020

Even if warts are not parasitized by these tongue-in-cheek horrors, they are still very strange, Evans told Live Science.

“They have a second set of jaws in their throats, like in the movie ‘Alien,'” he said. “Wrasses can swing a snail, and then they can actually generate enough force with the second set of jaws to scratch the shell in their throat.”

Some wrasse called parrotfish have copper-reinforced beaks that are hard enough to bite through coral. And the slingjaw wrasse (Epibulus insidiator) can launch its jaws forward up to 65% the length of its head, to cut off elusive prey.

“It’s like when you saw a Cheeto on the other side of your kitchen, and you just threw your jaws on it while you were standing in its place,” Evans said.

Originally published on Live Science.