[ad_1]

Jakarta, Indonesia – Questions about the potential use of pork products in vaccines are compounding concerns about vaccines in Indonesia, experts warned, urging the Southeast Asian nation’s Muslim officials and leaders to accelerate efforts to win public trust. before a mass immunization campaign against COVID-19.

Pork gelatin is used as a stabilizer in some vaccines. But the consumption of pork is strictly prohibited or “haram” for Muslims, who comprise 87 percent of Indonesia’s 273 million people, raising concerns that this may hamper vaccination in the Southeast Asian nation. most affected by COVID-19.

Dr Dicky Budiman, an epidemiologist who has helped formulate the Indonesian Ministry of Health’s pandemic management strategy for 20 years, said that a halal certification for COVID-19 vaccines was essential.

“Halal is more than just food: it more incorporates all aspects of the lifestyle of practicing Muslims,” said Budiman.

“If you are doing business, you must do it halal and not mislead people. When it comes to vaccines, halal certification is practically mandatory in Indonesia because it ensures that the production process from start to finish is in line with Islamic teaching. “

The Indonesian government has been praised by health experts for not pinning their hopes on a single COVID-19 vaccine. It has submitted binding orders for 100 million doses of AstraZeneca, 50 million from Novavax, 50 million from Pfizer, 53 million from COVAX / GAVI, a global body that works to ensure poor countries have access to COVID-19 vaccines, and another 125 million. from China Sinovac.

However, the government has yet to approve a single vaccine candidate.

AstraZeneca, Novavax and Pfizer have said that their vaccines do not contain pork products. But Sinovac has declined to disclose the ingredients in its COVID-19 vaccine or specifically say if it has pork gelatin.

The MUI, Indonesia’s main Muslim clerical body making decisions on halal certification, also appears to be asleep at the wheel. He completed his study of the Sinovac vaccine a month ago, but has yet to announce his decision.

“Many people in Indonesia believe in conspiracy theories about COVID-19 and one of the reasons is that the government has not had a clear strategic communication campaign,” Budiman said. “Sinovac must also be very clear about the ingredients in its vaccine and the MUI must announce its decision on halal certification without further delay.”

‘It was a disaster’

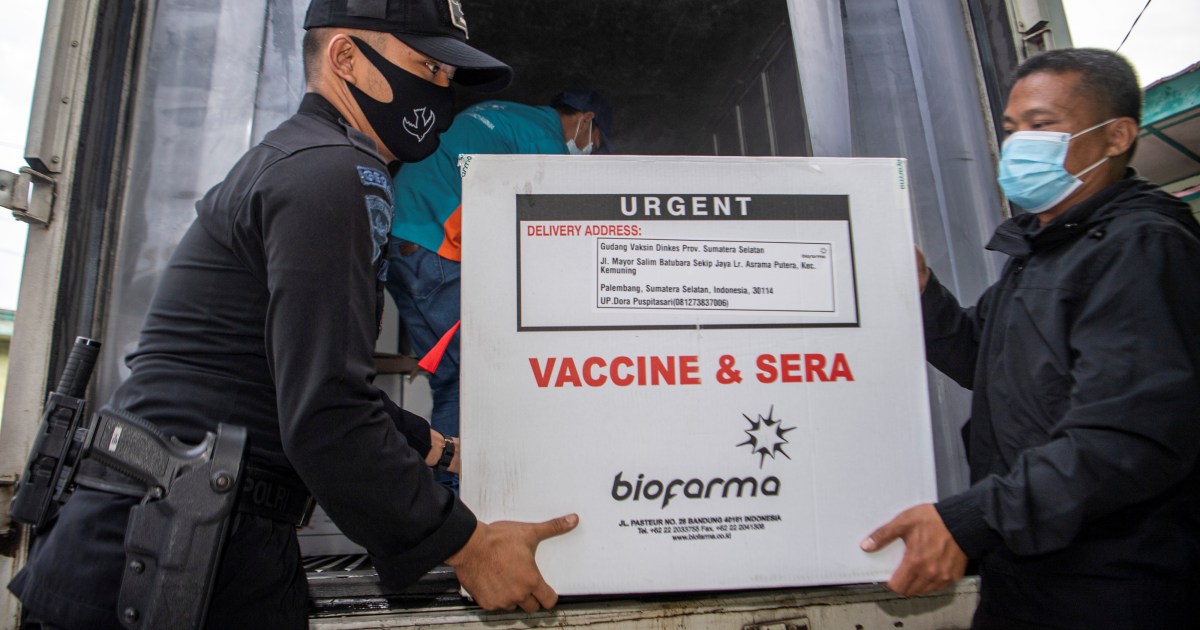

Indonesia, which has reported more than 758,000 COVID-19 infections and more than 22,500 deaths since the start of the pandemic, has already received three million doses of the Sinovac vaccine and expects to receive doses from AstraZeneca and Pfizer in the coming weeks.

But with authorization and halal certifications for the vaccines still pending, it is unclear when the country can implement its inoculation program.

Ahmad Utomo, a molecular biology consultant in Jakarta who specializes in diagnosing lung infections, said the government’s failure to assuage concerns about pork products in vaccines is a textbook example of its inability to communicate with the public during the pandemic.

“The issue is one of public trust. There is deep mistrust against the government when it comes to COVID-19 which was compounded by poor scientific communication from Purwanto in the early stages of the pandemic, ”he said, referring to the former Indonesian health minister, who infamously said that the country was immune to COVID-19 due to prayer.

“The aggressive gestures of some government officials for vaccinations to begin in November when there were no signs of efficacy of the vaccine or BPOM [Indonesia’s agency for drug and food control] the approval was also unproductive, ”he said. “Scientists have been caught in the middle. It was a disaster. “

Vaccine hesitancy has been on the rise in Indonesia for many years and has worsened further during the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

A survey it conducted in August with the Indonesian Ministry of Health found that 27 percent of those surveyed were hesitant to take a COVID-19 vaccine, a group that the survey said was “crucial to a successful vaccination program.”

Their reasons ranged from religious beliefs, fear of the side effects of vaccines, and uncertainty about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

“I’m not sure I’ll take it because my aunt told me it had pork,” Vita, an observant Muslim woman in West Kalimantan province who, like many Indonesians, has only one name, told Al Jazeera. “Maybe it’s okay for Muslims to have it if there is a specific purpose. But he would have to study the Quran to find the answer. “

But Sadiyah said that halal certification does not concern him. “I am more concerned with the other ingredients. Will it make me sick or healthy? Because right now I’m healthy. “

Yasmin Libbing, a product specialist who supplies German medical tools to hospitals in Central Java, said hesitancy in the face of the virus was rife in her hometown of Semarang.

“Many people are against it and many are pro-vaccines. There is no agreement, ”he said. “But the doctors I talk to every day, they tell me they won’t trust them until all the clinical trials have passed.”

Obstacles ahead

The joint survey by the WHO and the Ministry of Health also found that a third of Indonesians who want to get vaccinated against COVID-19 were unwilling or unable to afford it. Before being replaced in a cabinet change in December, former Health Minister Terawan Agus Putranto said the government plans to cover the cost of just 30 percent of the 107 million people marked to receive COVID-19 vaccines for 2022.

Following public reaction, President Joko Widodo jumped into the fray and said that COVID-19 vaccines will be free for all Indonesians.

Budiman praised the move, saying that free vaccines were essential to achieve herd immunity during pandemics.

“But the government should have a clear strategic communication policy to address the ‘infodemic’ and provide the public with accurate data on the effectiveness and risks of each vaccine to prevent rumors from growing,” he said. “That way, people can decide whether they want to get vaccinated or not.”

MUI is expected to approve COVID-19 vaccines containing pork gelatin, citing the common good. But if the past reaction of the Indonesian public to other vaccination programs is based on anything, embracing the coronavirus scheme could prove difficult.

Between 2017 and 2018, Indonesia carried out the world’s largest vaccination campaign against measles and rubella. More than 67 million children were injected with a new combined measles and rubella (MR) vaccine from India.

The first phase in 2017 was a success, with more than 35 million children vaccinated on the main island of Java. Measles and rubella cases were reduced by more than 90 percent.

But things turned around in 2018 when the MUI in the Riau Islands, an archipelago scattered between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, claimed that the MR vaccine contained pig gelatin and was therefore banned.

The Jakarta MUI issued a statement supporting that assessment, and subsequently in Sumatra, Indonesia’s second most densely populated island, the RM immunization rate was reduced to 68 percent. In Aceh, an ultra-conservative Muslim province in the extreme northwest of Sumatra, the turnout has dropped to just 8 percent, according to the Health Ministry.

The MUI tried to back down with a follow-up statement saying that the MR vaccine is allowed for Muslims. But by then, measles cases had skyrocketed. By 2019, Indonesia had returned to where it was before the campaign with the third highest rate of measles in the world.

The seminal British medical journal The Lancet said that doubts about vaccines were increasing globally and that Indonesia’s experience with the MR vaccine was a warning.

“Political leaders and ministries of health must continue dialogue with religious scholars and communities to generate a common understanding and unequivocal message about the benefits of immunization,” the magazine said. “The health and survival of Indonesian children depend on it.”

[ad_2]