[ad_1]

The Apollo program demonstrated that humans could land on the Moon and do useful work, but due to logistical and technical limitations, individual missions were kept short. For the $ 28 billion ($ 283 billion adjusted) spent on the entire program, the astronauts only logged about 16 days in total on the lunar surface. In comparison, the International Space Station has cost an estimated $ 150 billion to build, and has been continuously busy since November 2000. Apollo was an incredible technical achievement, but not a particularly profitable way to explore our closest celestial neighbor.

Building on the lessons learned from the Apollo program, modern technology, and cooperation with international and business partners, NASA has recently released its plans to establish a sustained presence on the Moon in the next decade. The Artemis program, named after Apollo’s twin sister, will not be just a series of unique missions. Fully realized, it would consist of not only a permanent outpost where astronauts will work and live on the Moon’s surface for months, but a lunar orbiting space station that provides logistical support and offers a testing ground for the deep. space technologies that will eventually be necessary for a human mission on Mars.

It’s an ambitious program in a short timeline, but NASA believes it reflects the incredible technological advancements that have been made since the last time humans abandoned the relative safety of low Earth orbit. Operating the International Space Station for 20 years has given countries practical experience in assembling and maintaining a large orbital complex, and decades of robotic missions have perfected the technology required for precision landings. By combining all the knowledge acquired since the end of Apollo, the Artemis program hopes to finally establish a continuous human presence on and around the Moon.

Orbital assembly

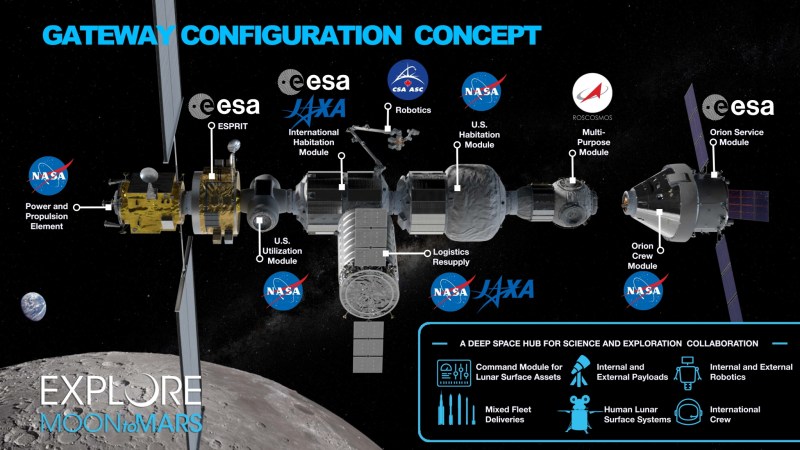

NASA says a space station orbiting the Moon will be an invaluable asset as the agency moves toward large-scale exploration and development of the lunar surface. This station, which the agency calls “Gateway”, would allow for more elaborate missions by providing a meeting point for crews and their spacecraft. For example, a lander larger and more capable than those used during Apollo missions could be assembled and verified at Gateway prior to the arrival of its assigned crew. After returning from the surface, the lander could be restored and refueled at the station to be used on another mission instead of being discarded.

Beyond supporting lunar activities, NASA says the Gateway could be used as a laboratory for deep space research in the same way that the ISS is for low Earth orbit. Its location would be advantageous for heliophysics studies and Earth observation, and work is already underway on several scientific modules that could be mounted outside the station.

Expanding on the relationships developed during the construction of the International Space Station, NASA will partner with Japanese, Canadian and European space agencies to develop key Gateway modules. While the details have yet to be finalized, the Russian space agency Roscosmos is also expected to eventually contribute its own module.

Despite the incredible payload capacity of NASA’s own space launch system, many of the Gateway modules are expected to eventually be delivered to the Moon by commercial launch vehicles to cut costs. The agency has also started looking for business partners who can make regular refueling flights to the station, and SpaceX has recently been awarded the first “Gateway Logistics Services” contract.

Preparing the camp

Looking further, NASA says they want to establish a permanent outpost on the Moon called “Artemis Base Camp” that can house multiple astronauts for months at a time. The exact location of the base camp has yet to be decided, but the proposal says that somewhere near the South Pole is the logical choice, as it would offer long stretches of sunlight and a direct line of sight back to Earth. Various references are made to the area around Shackleton Crater, as large deposits of water ice are believed to lie on its dark bottom. The terrain in this area is also relatively smooth, which would greatly facilitate landing and surface navigation.

To that end, the proposal also mentions the need for various ground vehicles at base camp. The Lunar Terrain Vehicle (LTV) would be the modern equivalent of the “Moon Buggies” that became famous during the Apollo missions, while the Habitable Mobility Platform would be a much larger vehicle capable of withstanding long walks away from the Camp. Base. Without this mobile command center, NASA says astronauts would not be able to explore much more than a few kilometers from base camp.

Over time, the Artemis base camp infrastructure will expand and improve. Additional facilities would be built that would provide everything from power generation to waste treatment as NASA gains hands-on experience building structures on the lunar surface.

NASA does not give any kind of timeline for the establishment of Artemis Base Camp, other than saying it will happen sometime after Artemis III’s planned mission in 2024, which would see the first human landing on the Moon in more than 50 years. A facility of this scale would likely take decades to build, but given the agency’s goal of establishing a permanent presence on the Moon, that’s not necessarily a problem.

Dream vs reality

NASA finalizes the thirteen-page proposal by saying the lessons learned during the Artemis program will put the agency on the road to a human mission to Mars sometime in the 2030s. It says a fully realized Gateway could allow crews to train for the month-long flight to the Red Planet, and that surface vehicles developed for the Moon could easily be reused for Martian use. The Moon can never be a perfect substitute for the unique challenges of a human mission to Mars, but there is little doubt that further experience operating outside of low Earth orbit would be beneficial.

That said, until the metal bends and the hardware is released, it’s all just an idea. As we’ve seen time and time again with major NASA projects, securing the necessary funding is always a challenge. The agency also has to contend with political whims, as a decades-long program would require the continued approval of multiple presidents. In reality, there is absolutely no guarantee that astronauts will one day leave Base Camp in their LTV vehicles to explore the rim of Shackleton Crater; but we can wait