[ad_1]

Although the proposals from other countries were general in nature, New Zealand and Singapore initiated the Commodity Trade Declaration to Combat the Covid-19 Pandemic (Declaration) on April 16, 2020. The joint declaration includes the abolition of tariffs and the harmonization of other import and export procedures. Any member of the World Trade Organization is supposed to agree to the declaration of the abolition of all customs duties and other tariffs, and refrain from adopting non-tariff barriers to the list of commodities contained in two annexes. The first appendix includes 124 products divided into four groups: drugs, medical supplies, medical equipment, and personal protection products. The second appendix contains an additional list of 180 commodities that are primarily agricultural products. On April 3, 2020, the WTO Secretariat published an evaluation study of some 96 commodities, with the aim of liberalizing trade in medicines. This list also includes electronic medical devices and equipment.

The aim of the “declaration” and the study appears to be an attempt to broaden the coverage of multilateral (sectoral) agreements, the “Pharmaceutical Agreement” and the Information Technology Agreement (ITA). Multilateral agreements are negotiated between smaller groups of countries within the framework of the World Trade Organization.

Business negotiations are all about time. Once again, these efforts demonstrate that the WTO negotiations are not about development and sustainability, but about protecting and promoting the trade interests of developed countries, as they have always been.

Once again, the focus is on the massive elimination of tariffs. Singapore and New Zealand, which advocate free trade in “commodities”, together account for no more than 3% of total world medical equipment imports. Additionally, Singapore’s tariffs on medical equipment are zero percent and New Zealand’s tariffs are 0.8 percent, which means that the cancellation of tariffs does not cause disruption to local producers. Developed countries often rely on national standards and measures to regulate imports.

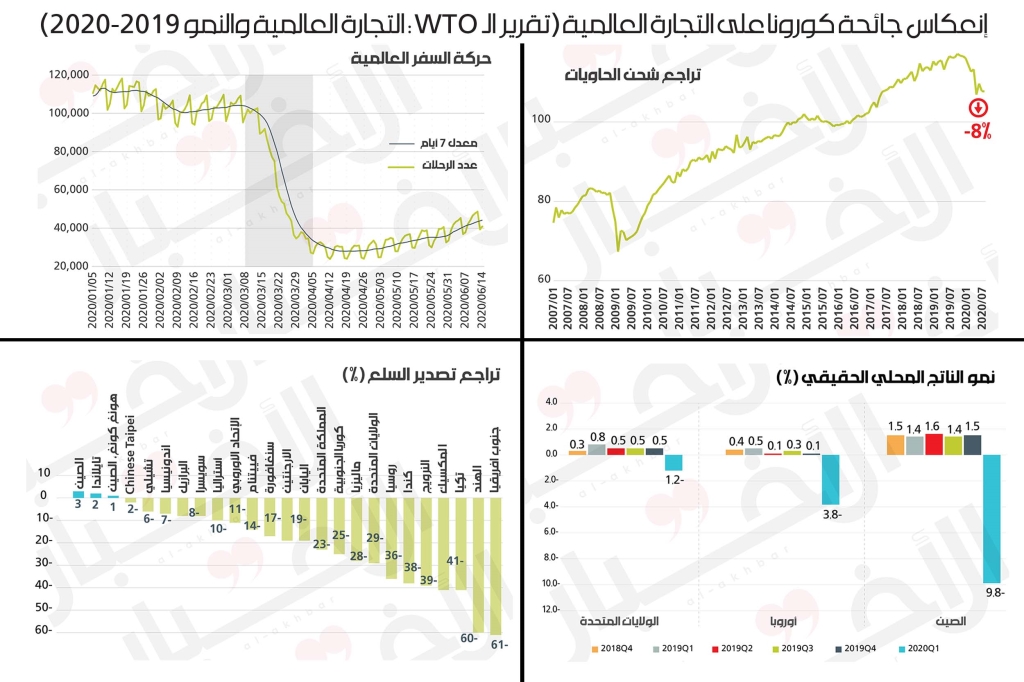

Click on the chart to enlarge it

Unfortunately, tariffs (based on value added) remain the main obstacle to imports in developing countries. For example, the average Indian fee for medical equipment is around 9%.

Therefore, the reduction of tariffs serves to create a wide margin for producing companies, especially from developed countries, to access our markets. Increased competition for imports during the economic downturn caused by a national shutdown will result in a loss for local medical equipment manufacturers. The use of national measures and regulations to address our concerns without tariffs is rare throughout the developing world.

During the pandemic emergency, the World Trade Organization can play a role in working to eliminate supply chain disruptions in medical and agricultural commodities. However, eliminating tariffs is their least immediate concern. Importing countries that charge higher tariffs on drugs (and high import requirements during this period) may unilaterally decide to reduce them temporarily, taking into account the concerns of their domestic industry. Rather, it is necessary to address the concerns of exporters with small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries, which include stricter industry standards in developed countries and compliance with third-party compliance requirements. The current path taken in the World Trade Organization only highlights the agenda of the developed world.

India was one of the first to participate in the Information Technology Agreement (ITA-1) which abolishes tariffs on 217 information technology products. It ended in 1995 among 82 members, representing about 97% of the world trade in IT products. At the Nairobi Ministerial Conference in December 2015, more than 50 members agreed to expand this agreement, which now covers 201 additional products valued at more than $ 1.3 trillion annually. India did not become a party to this deal after learning the lesson of the deal’s disastrous impact on domestic IT hardware producers.

The possibility of signing a medical products agreement means the merger of two multiple parties: the pharmaceutical agreement and the expanded ITA agreement, because it covers 11% of the products under the expanded ITA agreement. The other dimension of the current medical supplies proposal includes products that were also present in the Health Sector Proposal NAMA 2008. The announced regulation covers 25% of the products in the NAMA sector. Both clearly mark the beginning of the expanded coverage of trade liberalization targeting large markets like India.

Tables 2 and 3 clearly refer to the “facilitation” process that the WTO has undertaken for a small number of countries. Any liberalization by the participating countries through the “declaration” would “facilitate” the countries of the European Union, the United States, China, Japan, Mexico, Switzerland, Singapore, Ireland and Korea, which represent 90% of world exports of medical equipment. Among them, China is the only developing country with supply capacity; The value added by multinationals in Chinese manufacturing is known to be quite low.

India imports 2.2% of medical equipment, but its share in exports is only 0.5%; Therefore, it would be unwise for India to join in this statement. Similar to the 1996 Multilateral Agreement (ITA-1), the liberalization of tariffs without support for industrial policy, including measures and technical standards directed at the national level, will virtually eliminate the productive capacities of developing countries such as India in the United States. medical equipment area.

Once again, the efforts of the World Trade Organization negotiations show that they are not related to development and sustainability, but to the protection and promotion of the commercial interests of developed countries, as they always have been.

The tables show the pattern of high demand and supply among the United States of America, the European Union, China, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Singapore, and South Korea. Instead of proposing an agreement on medical products, these countries should make bilateral agreements!

Until now, most of the suppliers (companies) that benefit from the liberalization of customs trade in the framework of the WTO are developed countries that offer products that comply with the regulatory standards established by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) or industrial organizations. private or related. All WTO negotiations are purely commercial agreements within the framework of the imposition of the standards of the leading company / industrial agency / country that exports these products. In the absence of adequate discipline of non-tariff measures at the global level, countries such as the European Union, Switzerland, Japan and the United States will have free employment in supplying about 71% of the world market for medical equipment.

The 135 products included in the medicinal products (list of products compiled from the study and WTO declaration) are essential. However, for India, electronics and medical products are strategic sectors. Therefore, bearing the burden of further tariff liberalization under any World Trade Organization proposal, without domestic industry standards, will not serve India’s strategic interests.

The advanced members try to play with the old tricks that some of them have mastered during more than seven decades of international trade negotiations. This is a reminder to the South that even in the event of a pandemic, the North only cares about standardizing the market shares of companies. Developing and least developed countries need to beware of old ways that creep into emerging global trade rules. This is a call for the urgent need to reform the organization to eliminate data gaps and information asymmetries.

* Murali Callumal is a professor at the World Trade Organization Study Center (IIFT). Smitha Francis is a consultant at the Institute for Industrial Development Studies (ISID), New Delhi.

(This article was published on May 1, 2020 at https://www.policycircle.org/economy/wto-using-covid-to-push-expansionist-free-trade-agenda/)

Subscribe to «News» on YouTube here