[ad_1]

Translation: Samir taher

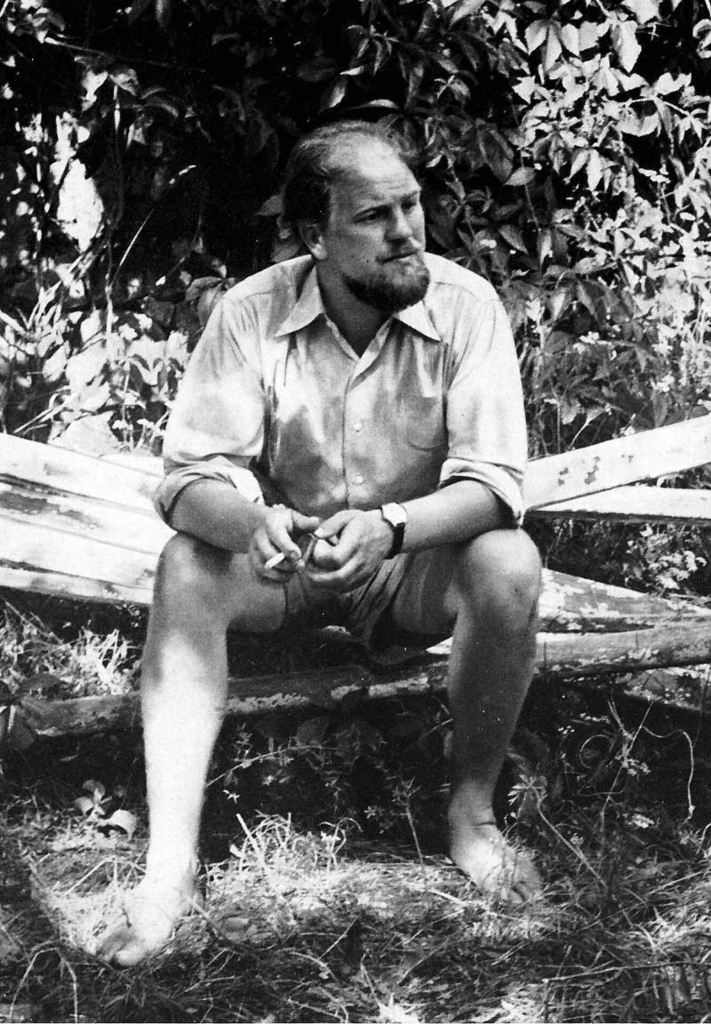

I have some messages to take care of with tenderness. It is not much, but it covers a period of twenty years. The sender is the poet Stig Khuden. The first message is dated October 1971 and begins with this: “My brother is on the most difficult roads.” I was twenty-three years old, working in the iron factory in Sandviken city and still living with my parents, and at that time I wrote my first poem on scraps of paper while I was in front of the machine that dented the steel strips and my fiancée printed on your printer. It happened that the one who would become my stepfather, who was also an educated worker in the iron factory, saw my clumsy writings and convinced me to accompany him to the Sandviken Public Library to hear from a real Stockholm poet.

The poet recited some of the poems from his poetry group “The Clear Language”, and that was my first meeting with the poet Stig Khudin. He was confused and hesitant, as I had great respect for him. But he spoke kindly to me, took my seven poems home to Stockholm, and responded with a message of encouragement:

“… you should send your poems to newspapers and magazines to check your position. The poems will be returned to you (not published), but each time you take the dowry to the car, you will feel better. Little by little, gaps will be created in their resistance to you. “

I did what he told me and sent my poems to three union magazines: Metal Workers, Government Workers and Construction Workers. Even though Stig Khuden said they would give me my poems back, what happened is that the three union magazines bought me poems! Three! The problem is that they all bought the same poems. I was forced to contact the culture departments, which at that time had a presence in the union press, and admit my mistake and admit that I was a rookie. However, the editors were very nice to the 23-year-old Sandviken ironworker, and we renamed each poem to have a different name in all three magazines. This was the beginning of my life as a writer. And it was the poet Stig Khoden who pushed me to dare.

The modern Khudin language shines and sparkles with clarity and focus as if it were the operations of the iron factory and its machinery.

His latest letters are dated November 12, 1992, more than 20 years after that anniversary. By this time, I had established myself as a full-time writer and published collections of poetry and novels, and the poet Stig Khuden became my friend and idol. Around this time, Stig learned that he had lung cancer and wrote to me:

“Even though this damn cancer I was carrying with cigarette smoke says it stops on X-rays, I think my breathing is getting heavier anyway. “It could be that this is the fault of the beautiful November weather, where it is gray and gray outside with rain and weather reminiscent of stomach ulcers, and there is no music inside.”

A few months later, his collection, “The Book of Traditional Medicine: The Journey of Descent”, arrived in the mail signed with his gift. Three weeks later, news of his death came, so I attended his funeral in Stockholm with the feeling that I was burying my father for the second time. Many think that his collection “A Piece of Soot” is his first publication. But previously he had published two collections: “The Sleepwalker” (1945) and “The Summer Sermon” (1947), both strongly influenced by Swedish modernists of Finnish origin, such as Edith Södergran, Elmer Dictonius and Gunnar Burlin. But it was “A Piece of Soot” published in 1949 that deservedly drew attention to Stig Khudin, the Labor poet. Critics in the country have woken up in surprise to see the phenomenon of the “workers poem” take on new life, after many believed it was over. And this time, it was not just a repetition of old models (such as romantic lyric poetry about coal workers, or balanced idealistic poetry that echoes popular demonstrations), as the liberation of that group ignited the confrontation between readers of lyrical poetry and the modern Khudin language, as it is a language that shines and sparkles with clarity and focus Iron Plant and Machinery. At the same time, these readers saw in Khudin’s poetry a passion and bitter realism that had not been hijacked by darkness. In the collection “A piece of soot”, it could be said that Stig Khuden made the first poetic representation of the workers of modern industry. It allowed them to break in, get dirty, sweat and just disguise themselves as literary salons. Only then did the people of Sandviken discover that they were lifting a working-class poet in their arms.

Khudin is a very emotional poet. The taste and aroma of Sandviken are always present in his poetry. He is also a singular lyrical poet on the themes of love and nature. Social criticism and environmental issues have always been recurring themes in his literature. While editing the union magazine Forest Industry Workers, he refined arguments that are still valid today. He had a broader intellectual and creative space than most poets.

Like all young employees at Sandviken, Stig began working in the large ironworks after his school day. This was in the early 1930s. Choosing this path was easy, as initially there was no other option. Growing up in a working-class family that works in the village factory means that you will also inherit this future, which is the future of your neighbors, colleagues and family members. This future poet was accumulating important experiences in those contaminated sections of the iron factory, and worked during that long period, seven years, in the pipe factory. Little by little, the need to write poetry takes hold. To be sure, that need was largely an escape from harsh reality.

For most people, the important events of adolescence can be first love, a first trip or the like, but for Stig Khuden his important event was a snapshot of his daily life, a different and very special snapshot. He had spoken on more than one occasion about the day when he approached an older co-worker who was standing in front of a tube-making machine and asked the routine question: How’s work going? His question was in a usual daily phrase, but the answer he received from his colleague this time was decisive for him, and will continue to be decisive for the rest of his life: tubes in this hole, and it is not full. The hatch never is! “The co-worker has shouted the message. With those words he was describing Stig’s future at the iron mill. That was the moment when he decided to become a poet and began to” practice scale, “as he put it. But he never dared to tell anyone around him that he wrote poetry, he didn’t want to seem different to others, in a bad mood.

Social criticism and environmental issues are recurring themes in his literature.

Stig described his emotional state as a young agent saying: “A lot of fear, a little blind anger and a huge amount of idealism.” And he expected the criticism he would receive from his co-workers if they found out about his commitment and activity in the Social Democratic Youth Union and the Workers’ Education Union, as they would comment saying, for example: “There are people who do anything that is not to work! ! ” And no one couldn’t be affected by such harsh comments, not even Stig, so he remained silent.

Through political activity and academic courses at People’s High School, he broke with his social legacy that marked everyone’s being in working-class society at that time, and perhaps also today. In 1943 he moved to Stockholm and would live there the rest of his life.

When he arrived in the capital, he sold many poems and articles to the union press, worked as a mail clerk, then as a worker in a workshop, before finally beginning his literary appearance. When the “Piece of soot” collection appeared in 1949, Stig Khoden was creating a completely new form of work poem, despite attempts by bourgeois critics to find in his poetry traces of the American poet Edgar Lee Masters (1868-1950) in his imaginary epithets included in his well-known collection. Spoon River Anthology ».

It can be suspected that Stig Khudin – thanks to his group “A Piece of Soot” – had found his language and followed the paved road at a comfortable pace, but the group that followed that, “The Night Visit”, was very different from its predecessors. It did not appear, in any way, as an apology to offer to those who, in the 1940s, saw that he “wrote a simple inflator about the iron factory”, but rather seemed to fear that he would put himself in a political position. which would make him a second-degree “used poet.” He wanted to be completely free in his poetry. Instead of the rattle and dirt of the iron factory, the group “Night Visit” highlighted that their idol now, and their starting point, is their grandmother. He describes it as “pious, pagan, upright, full of popular speeches and beliefs.” His grandmother definitely meant a lot to him and granted her a special place in his latest collection of poetry. “My grandmother opened me up and gave me life,” he says.

After two more collections of poetry, Stig fell silent. Some thought that this silence would last forever. It is true that she wrote journalistic materials, introductions and other things, but the poetry has almost disappeared. It was 11 years of silence. In an article, she talked about her alcohol addiction problem. But in the end she got rid of the addiction to alcohol. Then she told me that she saw her poetry collection “The Poplar Rajraj Tent” published in 1959 as a dead end, so how could she go on and find a language and a platform for the next poetry collections?

The comeback was very convincing. On his second hit with his group, “Do you have a problem with the flag?” Issued in 1970, it announces, from the beginning, its new vision that comes to him like a voice in a cemetery:

“All you have to do is move forward honestly

Go straight and then left towards the heart.

And ignore the birds

No one can explain his words.

Your theme is people

From them you will come with words,

Then you will be present.

It was as if Stig, after all these years, had come to the certainty of belonging – despite everything – to the environment of the language of his group “a piece of soot”, between the coffered ceilings and ordinary people. It is, in fact, that ancient perception of a person’s inability to escape from their origin, as this is where their language is stored.

Only in this group (Do you have problems with the flag?), Go back to the factory and the poem portrait. Three years later, her group published “The Strong Taste of Life”, in which she rewrote the concept of monotony from her own experience. In her other collection, Illustrated Wallpaper, the central character in one of her poems is that of an iron foundry. And in the collection “Letters of the Bast” (relating to the letters that were written on the bark of trees in the Middle Ages) published in 1988, the portraits illuminate the crown of the experience of the old poet, whose appeal and presence are deepens day after day. It seemed as if the poet had finally arrived home.

Stig Khuden died of lung cancer in 1993 and is buried in Stockholm. And on his grave he recorded these words quoted from his poetry:

“من خلال وصفنا للحب, نُِِِ الخوخوخو الخوََفَ.”

Burnet Olof Anderson: Swedish writer, novelist, playwright and poet.

The article was published in the Swedish magazine Class

Subscribe to «News» on YouTube here

[ad_2]