[ad_1]

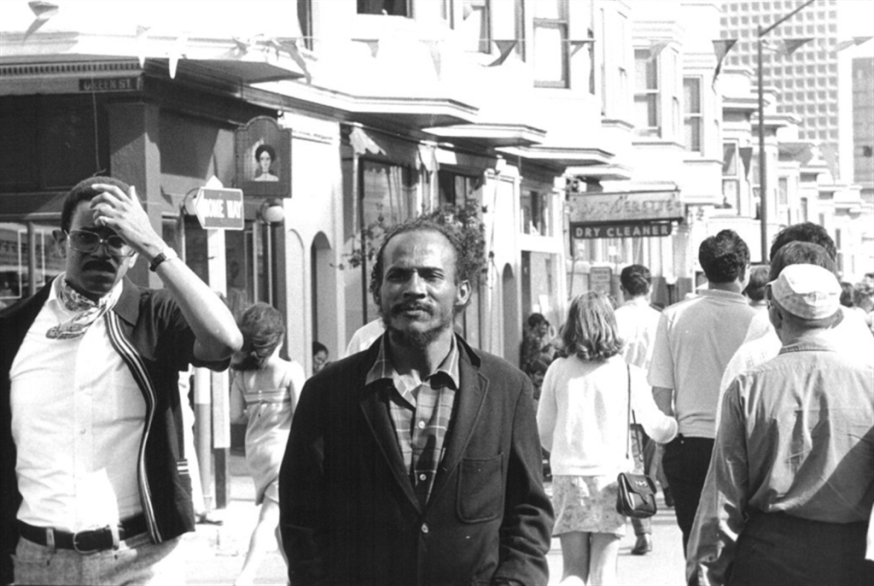

“Screaming louder than pain, we forgive ourselves; / Original sin seemed to be a broken cylinder. / The Lord played the blues, to kill time, all the time. / Red rivers brought us to life” . Before his poetry, the biography of Bob Kaufman (1925-1986) and his life in the alleys far from all American literary institutions is always restored. The outcast poet was long absent from critical writing and academic studies, and even from the “House Generation” movement, which was long considered the sterile voice of American poetry. Perhaps this exclusion is an extension of the experience and biography of the American poet whose arrival was delayed in the Dhad language, or is an obvious fulfillment of his desire to be forgotten as he once said: “My ambition is to be forgotten.” In contrast to the emergence of House Generation names and stars such as Alan Ginsburg, Jack Kerouac and others, his name was absent for years, although stories from San Francisco in the 1950s confirm that he was the first to step onto a table of bar and her hair screamed like she was making a fight. After a life of laziness, isolation, demolition, and direct conflict with the American authorities, critics agreed, shortly after his death, that he embodied the true spirit of rebellion in American poetry, as well as inspiring later generations of poets. blacks in America. Kaufman did not publish any Arabic translations until last year, signed by Iraqi poet and translator Muhammad Mazloum, for his early “isolation filled with loneliness” (Al-Jamal publications). This time Kaufman returns to Arabic again, in the collection “The saxophone of life in the mouth of death” (Al-Med publications), which contains poems chosen and translated by the Palestinian poet Samer Abu Hawash. There is no doubt that Kaufman’s language difficulty contributed to his late arrival in Arabic. It is difficult for readers of the English language, thanks to its linguistic derivations and its special effort in which it introduced to English the vocabulary of the street, especially the colloquial and vulgar black language. In his poems, the poet combined separate worlds, carrying the influences of surrealism mixed with a raw political soul and jazz music; That rhythm that continued to carry his poetry, with all its flow and improvisation. Although he moved between the southern United States, where he was born in New Orleans, and between California and New York, Kaufman spent most of his life in San Francisco. As in poetry and language, Kaufman was a sailor on his long ocean voyages that brought him to the shores of Africa and India. However, his early incorporation into the “National Maritime Union” put him in danger, especially as the police accused the union of sympathizing with communism. This was the beginning of a series of prosecutions by the US police and even the FBI, which left him for months in cells and psychiatric institutions, where he was subjected to treatment with electric shocks. He once compared the San Francisco police to Hitler. These prosecutions and surveillance left him unemployed for a long time, mainly as a result of the apartheid regime in the United States. Kaufman described America as the “dark plastic jungle,” while continuing to undermine American culture in his poems and language. In the late 1950s, similar to the statements of the poetic movement, Kaufman released a famous satirical manifesto called the Abomunist Manifesto (derived from the Atomic Bomb), which he published in the poetry magazine Beatitude, which he co-founded with other poets. Just as he protested his language politically, his silence was another protest as well, when he chose to remain silent for ten years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and did not return to poetry until the United States military left Vietnam.

[ad_2]

Subscribe to «News» on YouTube here