[ad_1]

Nonsense as a teenager? never; As we know from Tsvetáeva’s own confessions two years before her suicide that everything she loved, she loved before the seventh, and that everything that concerns her and gives value and importance to her existence was before the seventh: playing with the poetry before realizing what poetry is; Play with languages (you spoke three of them before the seventh) before realizing the rhetoric of the language. God responded to his wish after more than thirty years, that is why death granted him a suicide when he was forty-nine years old, after losing all his loved ones in death, exile and deportation, a husband, lovers, children, family and friends, and after her poetic sun faded and almost faded, to return as she always wanted to be: », unaware of the paradox that the bright lights she voluntarily sought for more than two decades to living under them, they will dispel the shadows and dispel your being at the same time. Only in the icy darkness that saw its last breath in Russia were the Bolsheviks whom Marina never loved, and who the Bolsheviks never liked. A life of painful ironies A life of permanent shadows, from when Russia was Tsarist, until Tsvetaeva was deported into exile, and even after she was forced to return to Russia, which changed and fought against all those who remained in her old obstinacy. Tsvetaeva had always lived in exile, even when she thought she would become the new crowned queen in the “silver age” of Russian poetry. He was a shadow in the field and a shadow in exile.

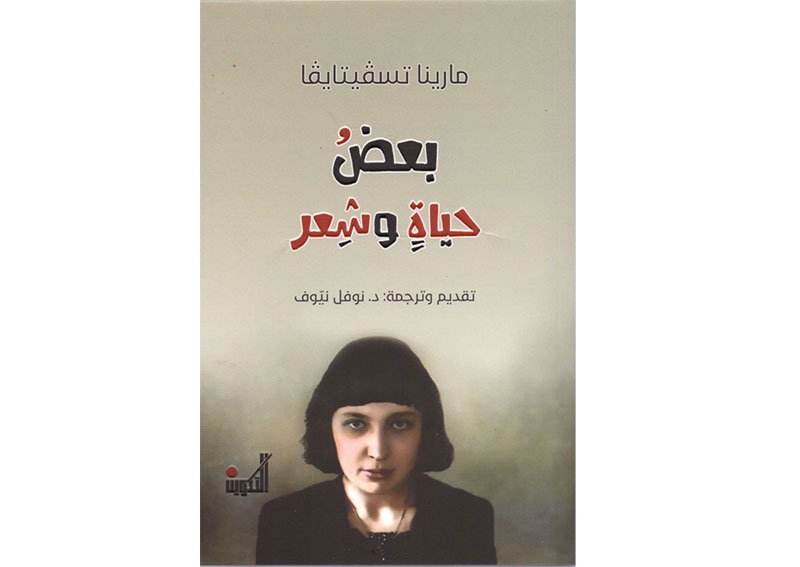

71 poems, complete or partial, that he wrote from the age of 17 until his suicide in 1941

The book “Some life and poetry” is divided into two parts, as its title indicates: “Some life” and “Some poetry.” They are preceded by a further introduction from the translator, followed by two appendices, the first of which contains excerpts from Tsvetaeva’s diaries, and the second provides an important history of the two encounters between the two greatest poets known in Russia: Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva, on which the translator relied on many references, from biographies, letters and diaries, most of which are not complete. In Russian, to remind us, albeit inadvertently, that the translation of the original language, creative texts or not, will lose a lot when they are translated from intermediate languages, since translations are often put to the test, especially on Russian, whose literature hardly we know of something other than literature. The “golden age” in the 19th century. The introduction and the two appendices give us many important clues to reading the poems of Tsvetaeva, whose life is inseparable from her poems: her singular childhood, her poetry-infused adolescence, the beginnings of her fame in Russia, and then in exile, the glamor of fame gradually faded, coinciding with the divergence of already few friendships. All this goes in parallel with the broader life of Russian and European cultural influences (French and German in particular), and the successive political influences that changed the map of Russia militarily, politically, socially and culturally. Russia is no longer the country of the golden age that marked Europe and the world with its distinctive character, and it is no longer even Russia based on cultural rivalries between literary schools, whether they were rivalries between the two great cities: Moscow and Petersburg, or among the great literary currents in which every writer and poet is in a different state from the others. Russia has become the prey of tougher political divisions that are no longer limited to the duality of internal and external, but have infiltrated everything to destroy singularities, friendships and rivalries, as happened in Germany in the Nazi era more late, and how it will happen in McCarthyal America, and how it happened and is and will happen in our damn region always, in the spring. Or without a spring, with military or civil dictatorships?

The anthology includes 71 poems, complete or partial, written by Tsvetaeva from the age of seventeen in 1908 until her suicide in 1941, and the prose section includes excerpts from Tsvetaeva’s diaries from 1917 and 1919, shortly before her departure into exile. Prose seems the best to him, perhaps because it is clearer, more intimate or more complete than poems. In prose, we get to know Tsvetaeva’s mind and heart without the arbitrary separation that we thought existed between them. He writes with his heart, not in the usual sense where emotions are wild, but in the sense of tenderness that delimits his relationship with language, the world and poetry even when he writes prose, where poetry is the body and is the soul, and it is country and it is exile, and it is love whose roots do not yield, be it love for her husband, her lover, Her poets from Rilke to Pasternak in person and poems. We do not feel this intimacy in the poems, perhaps because of their ambiguity at times, and perhaps because they are few or partial in most of them. This feeling is heightened when we read the appendix in which we find her face to face with her greatest rival Anna Akhmatova. The reader shares with Akhmatova his hesitation about Tsvetaeva’s poems, and perhaps this is because we know Akhmatova more (at least in terms of quantity), or because the splendor of any poet, no matter how high, will dim. before the fiery light of Akhmatova. This is the fate of one born in the time of a tyrant genius, just like the fate of Abu Firas when he synchronized the Mutanabi. However, the genius of Abu Firas shines when she does not look like Al-Mutanabi, and also the genius of Tsvetaeva that shines when she is herself, with her intimacy, isolation and the world of shadows, and in her notebooks that do not dispense of her, where “write-live”, where life is poetry and poetry is life, where constant longing for what is not, where love is death for Tsvetáeva who perhaps knows herself too much, and That is why he burned prematurely, when he committed suicide, “Not because it is wrong here, but because it is good there”, whatever, wherever and wherever, than “Over there”.

Subscribe to «News» on YouTube here